BACK in 1971, the celebrated Glasgow-born artist, Dr John Lowrie Morrison, won a travelling scholarship from the Royal Academy Schools in London. The scholarship was worth some £300 – a tidy sum back then.

Other youthful artists who were awarded the prize took themselves off on the Grand Tour – France, Italy, Holland. But not Morrison. He set his sights much closer to home: the huts at Carbeth, the community that had been established some half-a-century earlier, near the Campsies.

“My parents had had a hut there, and so did many aunts and uncles and cousins”, recalls the artist known as Jolomo, “although that’s going back to the 1930s. We had a hut near the swimming pool – I was a lifeguard for many years there”.

It was in many ways a frugal life, back then, but a hugely enjoyable one: endless amounts of fresh air and exercise, hampered not in the least by the fact that there was no water or electricity, or that calls of nature were dealt with by means of a dry Elsanol toilet.

Carbeth and Glasgow form Jolomo’s new exhibition, and the process involved him reaching back to his formative years. It’s called The Light of Glasgow and the Huts of Carbeth, and its paintings, with their vivid, expressive use of colour, are a reminder of why, at 72, he remains one of this country’s foremost contemporary artists.

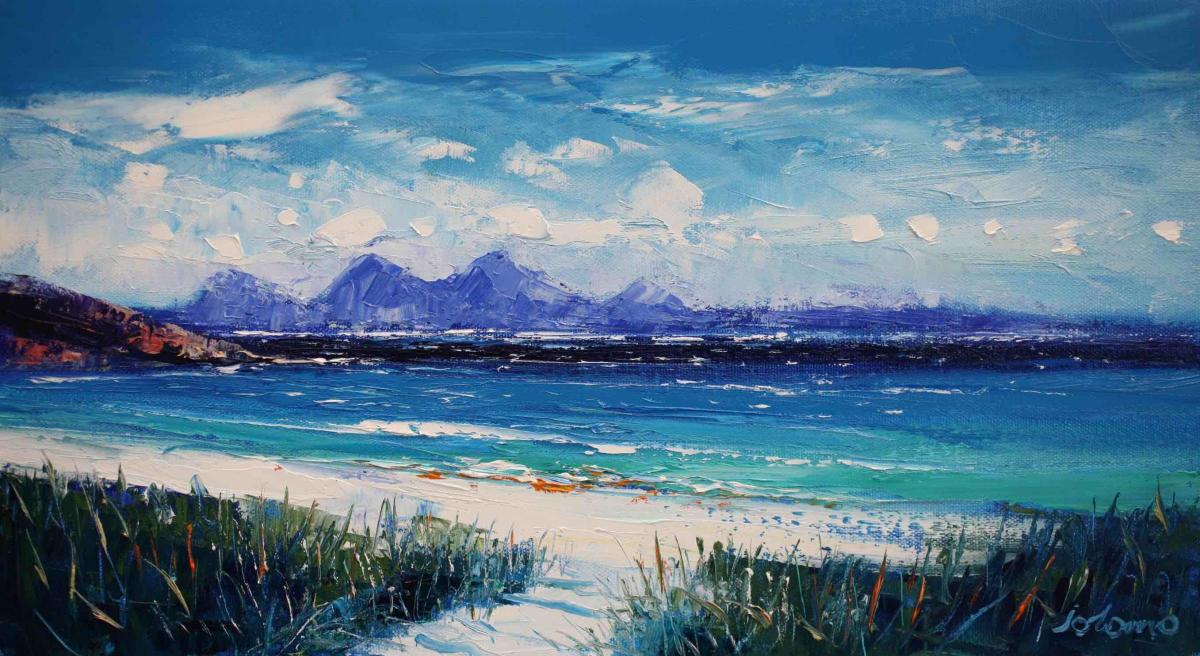

It's an interesting move from an artist who, in his own words, has spent the last half-century painting Argyll and the Hebrides, lighthouses, coastscapes, croftscapes, and the people and light of the Scottish west coast.

“I just felt that I wanted to draw and paint round about Carbeth, and particularly the Campsies – I’ve always loved Dumgoyne”, he says from his home in the fishing village of Tayvallich, in Knapdale, Lochgilphead. The large glass and steel studio in which he works is 20 years old this year.

“What I did was, I had a bike, and I cycled up all round the area, as far as Drymen and then Gartocharn. I painted and drew there, and I did a huge portfolio of work over several months. Various famous artists and professors came up from London to discuss my work and they said it was excellent and that I would go places as a painter. They are always very critical of my work so I didn’t believe them, but at the end of the day they were right.

“But the thing that I didn’t do, was to actually finish paintings. There were lots of pastels, there were lots of drawings, but I didn’t really do a finished painting. So”, he laughs, “this is me putting some sort of closure on Carbeth, in a way.

“I’ve always wanted to paint Carbeth, but the huts are really difficult to paint”.

Really?

“Aye – you do it but then you look at it, and you think, ‘That looks dreadful’.

"You’ve really got to work hard at it to get this feeling of – not so much even their look; but what I’ve tried to do with these paintings is to get my particular vision of it, my memories of it – just what it was like.

“The smoke coming out of the chimneys, for example – everybody had a wood-burning stove, and all that sort of stuff.

“But it’s always been a fantastic place. I just loved it. We used to go every weekend and on all the holidays. I think there were six members of our family there; there was all that kind of nice camaraderie, we used to muck in and have family meals together. It was a lovely, lovely time. With these paintings I just wanted to show it off a wee bit.

"They’re not so much huts now as chalets – I’ve even heard one or two people refer to them as ‘dachas’…” He laughs again. “And I think, ‘oh, come on…!”

Noting that many of the huts – or chalets, or perhaps, dachas – have their own generators now, Jolomo clearly has an abiding affection for those far-off days when lighting came from Tilley lamps or oil lamps, and meals were cooked on simple paraffin stoves (he still has one in his studio today). “It was so basic but it was absolutely fantastic. Every time I think about it, I jump up and down.”

The evocative Carbeth paintings in the exhibition range from A Hut With a View, Midhill, Carbeth, to A Winter Gloaming, Carbeth, a full moon in a chill sky overlooking spindly trees and a hut, a thin stream of smoke curling from its chimney.

Another memory occurs to Jolomo while we're talking: Joan Eardley, the renowned artist whose many subjects included Glasgow streets and children. The Herald’s obituary of her in August 1963 said she came to see city urchins with such a "new depth of understanding" that one eminent critic likened her to Goya.

“She died in Killearn Hospital”, Jolomo says, “Where our hut was, it was on the Cuilt Road, above Blanefield. My mates and I used to muck about in the woods when we were younger, pretending we were soldiers, as you did in these days, and I used to go this ridge and look down on the valley, and you could see right to the hospital.

“I was really into Joan in those days”, he adds. “I went to Hyndland Secondary; I’d be about 15, 16, ready to go to [Glasgow] Art School, and I can always remember lying in the long grass there, and looking, and thinking, ‘Gosh, she’s dying’. I said a wee prayer for her.

“It has always stuck with me. It’s one of these really weird things. Some of the buildings are still there, including the hospital, which is a wreck now, and falling to bits”.

Jolomo, who was born in Maryhill in 1948 (he coined the sobriquet during a Latin lesson at school, in 1962), studied at GSA between 1967 and 1971, but before he set foot in that gilded place he had already had his first exhibition, and sold his first painting (a copy of work by his grandfather).

It was in 1971 that he developed his “distinctive expressive style”, with blue as the key colour. This was a busy period for him. He did a post-graduate year in fine art, then studied teaching at Jordanhill College in 1972-1973.

In 1973 he relocated to Argyll in order to teach. He combined teaching with art, and his first solo show came about in 1976. He and his wife set up home in Tayvallich in 1977.

The very first Morrison painting to be signed ‘Jolomo’ was in 1985. He left Lochgilphead High School as Principal Teacher of Art in 1994, then worked as an Adviser/Education Development Officer with Strathclyde Region. He left education in 1997 to become a full-time professional artist.

Today, he is one of our best-known artists, with numerous exhibitions and accolades behind him. Books have been written about him. He has been profiled more than once on television.

His paintings of the west coast made him famous, and much-sought-after. What makes the area unique, he has always said, is the quality of the light.

"I love the way the light affects the landscape”, he said in an interview a decade ago. “You don't get the same bright colours, the same intensity anywhere else in the world."

Of his ability to depict vividly even the most seemingly neutral of shades, he said in the same interview, "That's where I see the bright colours. Most people see them only peripherally. I make them a big part of my picture. Having said that, if you go to Iona, or any of the white sandy beaches up the west coast, the water is green. People say to me, 'Where did you get the green water, son?' I tell them to get out more. Go and have a look.”

Despite having lived in Knapdale for more than four decades, Jolomo has a soft spot for the Glasgow he once knew so well. In the exhibition there are paintings of spring blossoms in Park Circus Place; a back-lane off Wilton Street; Kelvingrove, viewed from Park Terrace; and the demolition of tenements in Seamore Street, in North Woodside.

“I was brought up in North Woodside, then moved over to Hyndland”, he says. “Again, like Carbeth, it’s a wonderful part of the world. I think that’s where the city must have got the Dear Green Place label from, because the west end is just absolutely fantastic.

“I believe the city’s a bit tidier now, but I’ve been up here [in Tayvallich] for nearly 50 years”.

Has Glasgow changed much, and has it lost anything in the process? “It has changed, definitely, and it has lost something in a way.

“But, you know, I was glad to get away from it, because it was just black, grey and brown. It was filthy. It really was. The industrial revolution had taken its toll.

“I haven’t been down for a couple of years but I was down to the Glasgow Gallery, for instance, when it was opened, and I have seen around bits of the city. What I have seen is totally different, quite incredible.

“My last memory was of Charing Cross being ripped apart for the new road, when I was at Glasgow School of Art, and the Kingston Bridge was still being built.

“I was quite sad that all the different crosses were taken away”, he continues. “Charing Cross, and up at Springburn and down at the Gorbals. Anderston, too.

“These were all areas where people all gathered. They were the hubs of that particular village, if you like. It was the kind of village culture that London still has. It still has lots of little conclaves surrounding squares, and I think it was a mistake for Glasgow to get rid of them, particularly Charing Cross.

“I was interested to see plans earlier this year to cover over the M8 at Charing Cross. We should have gone underneath [in the 1960s]”

He remembers the Grand Hotel, a splendid edifice at the Cross that was demolished. “I was in the hotel for a wedding when I was a wee boy and it was like, ‘Oh my goodness’ – it was like Paris or something, you know?”

He also talks fondly about the years in which he wandered around the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum. He’s far from being the only artist to have been introduced to the power of art by its teeming pleasures.

“My mother always took me to the art galleries on a Sunday afternoon. From day one, when I was in a pram, she would push me around there and talk about the paintings.

“When I was a bit older, I can remember her saying to me, ‘You’ll be an artist one day, and you’ll go to Glasgow School of Art, and just remember all those beautiful, Parisian-looking buildings’. That has obviously got into my psyche.”

He touches on the painting of the demolition of the Seamore Street tenements.

“The first film I ever saw was in the Seamore Cinema, and it was Singin’ in the Rain [in 1952]. The place had millions of people in it. It was packed out. There were people sitting in the aisles, there were people standing down the sides and at the back, all to see Gene Kelly singing in the rain.

“Seamore Street was directly across the road from the cinema and just a block down from Simpson Street, where I was born and brought up in tenements.

“But the tenements were absolutely dreadful. I can remember, when I was a wee lad, going up from Hyndland Street and visiting cousins, the same ones who had the huts at Carbeth. Basically, I think why they had the huts was so that they wanted to get out of the slum”.

That said, the interiors of many tenement flats were better than their often grimy exteriors would have led you to believe. The very first flat that his parents moved into was a red-sandstone one in Queen’s Cross, with a bay window and marble fireplace, just across from the Mackintosh church.

“That’s what this exhibition is really all about”, he says. “It’s been in my system all my life. I’ve always painted tenements but I’ve not exhibited them. I’ve got hundreds of drawings from art school – when you’re at GSA you go out and you draw the local area, and my drawings are all in drawers here. They’re my three sons’ pension fund, if you like.

“But I just wanted to take the whole thing to a conclusion – not just the Carbeth thing but also the Glasgow thing. I just never did major paintings of them, and I think I’ve fulfilled it, a bit.”

Every now and again, he looks back on a successful and lucrative career, and wonders how a wee boy from Glasgow became so accomplished.

"I've been presented with several doctorates, and I have an OBE from the Queen. I've also been invited to Buckingham Palace to have a private lunch with the Queen, which was, of course, all a great honour.

"But I wish my folks were still alive to see their boy, a boy born in a room-and-kitchen in a Maryhill tenement, having lunch with Her Majesty? How did I get there?" he asks.

The Light of Glasgow and The Huts of Carbeth is at The Glasgow Gallery, Bath Street, Glasgow, until December 21. Tel 0141-333 1991. Jolomo’s website is at jolomo.com

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel