This time of year isn’t all candy canes and silver bells, you know. When it comes to the stories told at Christmas, it can get quite dark and scary. Writer at Large Neil Mackay unravels the twisted history of the Christmas story

UNLIKE nearly everything else associated with Christmas, the stories we tell at this time of year are anything but cute, comfy and cosy. Christmas stories are dark and frightening. From the ghosts of A Christmas Carol to children’s stories like The Lion, The Witch And The Wardrobe, these tales jar against the kitschness of gingerbread houses and pretty lights on the tree.

The reason why festive stories are so dark lies in the deep roots of Christmas. As far as we know, there’s always been some form of festival or ritual deep in the heart of midwinter in nearly all cultures – at least since primitive humans developed the concept of religion. We know our ancient ancestors staged important acts of worship at the winter solstice, which occurs around December 21 to 22 each year. This was a time to sit around a fire, while the wind howled outside, telling stories to keep the darkness at bay. Or a season of praying and sacrificing to old gods to keep evil from the home.

These ancient festivals were about the dying of the sun. On the shortest day of the year it seemed as if the sun was in retreat, or might never return, and that was a terrifying concept for primitive people. The Winter Solstice became a festival of death and rebirth – something the early Christian church picked up on when they chose late December as the date of the birth of Christ, another symbol of death and rebirth.

So the roots of Christmas lie in fear rather than simple celebration. As time rolled on, these winter celebrations adapted for different cultures. In ancient Rome it became Saturnalia. The Romans used the festival as a chance to explore fear. They turned the winter celebration into a time of misrule, when social norms were abandoned. Slaves were free for a day – theoretically. Saturnalia was edgy, to say the least.

The ancient Greek festival called the Dionysia was even more mysterious and threatening than Saturnalia. The festival for the Greek god of wine and fertility was a time of chaos and real danger. Revellers would get drunk and rites could be violent, with devotees in a state of wine-induced religious ecstasy. There’s still debate over whether human sacrifice occurred.

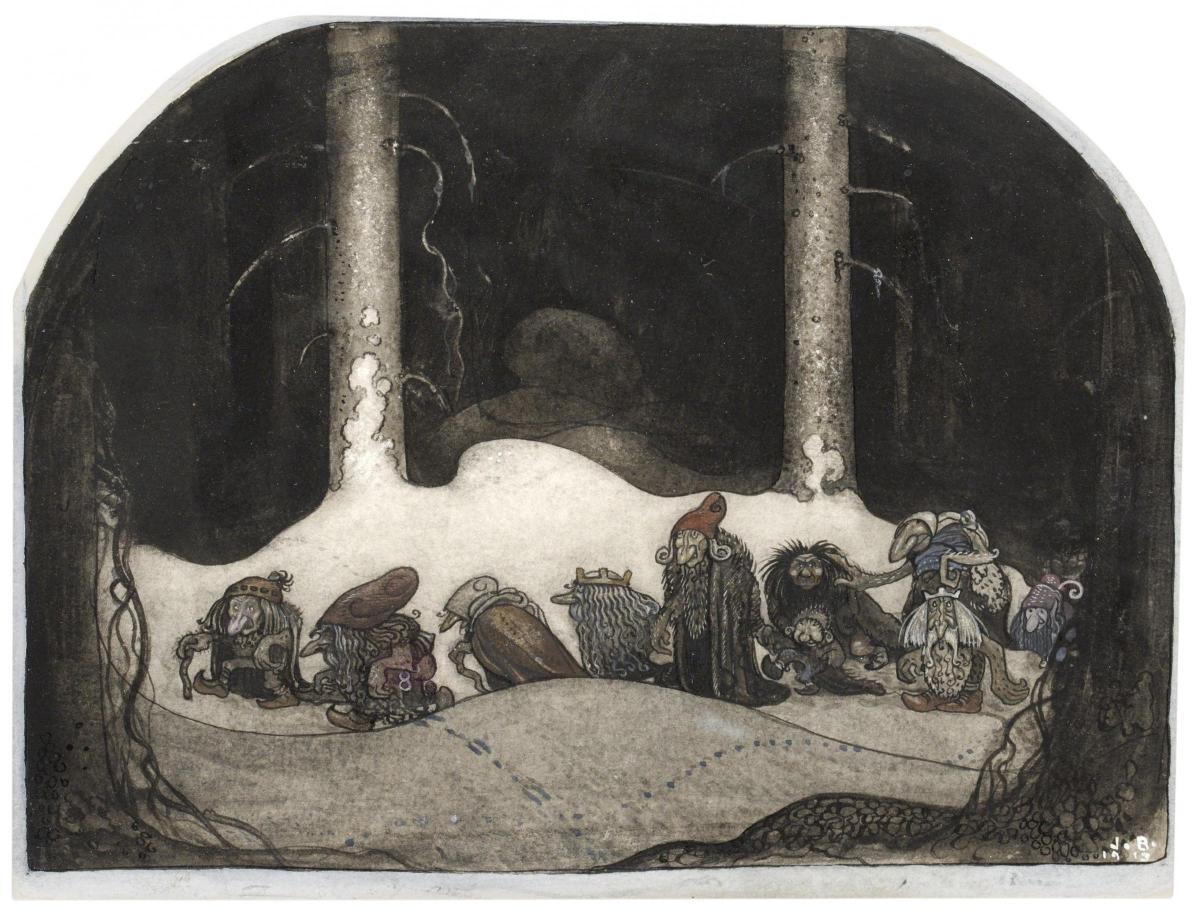

In northern countries and Scandinavia, the Dionysia is echoed in the Wild Hunt – one of the most frightening European midwinter myths. It sees supernatural hunters ride through the sky in the depths of winter terrorising human beings. The Wild Hunt is part of the Yule celebrations – a time when Germanic people made sacrifices to the old gods at the darkest time of the year.

These dark myths and legends live on in folktales we still know today. Jacob Grimm – of the Brothers Grimm – studied the folklore of central Europe including the Wild Hunt. We can see the festival of Yule and its stories of The Wild Hunt living on in the legend of the Krampus – a half-goat, half-human demon which terrorises children at Christmastime.

The Krampus probably has its origins in an ancient Germanic horned god – and may even have influenced early interpretations of Satan. Such legends are still alive and well and spreading fear. Just last week, Austria was up in arms over scenes of drunken disorder and violence when gangs of men dressed as Krampuses ran riot, beating people up.

Fairy tales

The spirit of the dark origins of Christmas even lives on in the stories of writers we consider to be among the most childlike and unthreatening. Take Hans Christian Andersen and his fairy tale The Snow Queen. Andersen’s story tells of the abduction of a little boy by The Snow Queen – who represents death. She is cruel, cold, uncaring.

It’s a thoroughly chilling and unChristmasy story. Its darkness may reflect the fact that Andersen was inspired to write the story after his romantic overtures to the famous Swedish opera singer Jenny Lind

were rejected. It’s said the icy-hearted Snow Queen was directly inspired by Lind.

The Snow Queen – one of the most enduring modern Christmas fairy tales – shows that the stories we tell at this time of year are not about peace and goodwill, or fun and games. They’re about loss, fear and death, harking back to those ancient legends of the past which our ancestors dwelled on

at midwinter and turned into religious festivals meant to banish darkness from their lives.

But for darkness, Hans Christen Andersen’s other Christmas fairy tale, The Fir Tree, leaves The Snow Queen standing. The story goes like this: an awkward little fir tree is desperate to grow up and become a Christmas tree covered it pretty decorations.

Finally, he’s cut down and spends one amazing Christmas Eve, decorated and with the family who bought him. The next day he’s taken down and stuffed in the attic. He’s lonely and tells the story of the wonderful day he spent to mice.

The mice leave and finally, when he’s withered and falling to pieces, the fir tree is taken into the yard, cut up and burned. A boy takes the star from the tree’s top branch. The End.

Christmas stories don’t do what Christmas movies do – they aren’t meant to make us feel all happy inside. They make us think of what winter meant to our ancestors – the people who lay down the storytelling foundations of Christmas with their ancient rites and tales. Christmas stories make this time of year a season of death, loss and dread.

Even Christmas fairy stories which aren’t designed to scare you are still pretty melancholy. Read Babushka – or Grandmother – a famous Russian folktale. Babushka never stops working. She’s always cooking and cleaning. Too busy to think about anything than everyday cares.

One Christmas the Three Wise Men call at her house looking for lodgings on their way to meet the baby Jesus. Babushka’s son died as a baby and the Three Wise Men kindly ask her to accompany them to Bethlehem.By the time Babushka is through with her chores, though, they have had to leave.

Babushka follows them, always just a day’s travel behind. When she arrives in Bethlehem, she’s too late. The Three Wise Men have left and Mary and Joseph have escaped to Egypt with the baby Jesus.

Babushka’s petty human concerns have robbed her of a chance of happiness, and now only death awaits her. Grim, eh?

Urban legends

If you think our Christmas folktales and fairy stories are dark, try our modern urban legends. These campfire tales have been doing the rounds since the 1950s, and when it comes to Christmas, the world of urban legends is a deadly place to say the least. There are stories like The Baby And The Pile Of Coats.

In the story, a young couple are having a Christmas party. All their friends are invited and told to throw their coats into the guest room when they arrive.

Unfortunately, guests toss their coats into the baby’s room, on top of the baby’s bed – and the baby is in the bed. By the time the party is over, you can guess what’s happened.

Children are often in the danger zone in Christmas urban legends. In The Poinsettia Plant, a young child attracted to the beauty of the red Christmas flower, eats the brightly coloured leaves, which are poisonous, and dies. In real life, poinsettia is irritating – it’ll make you sick – but it’s not going to kill you.

Nevertheless, in the land of urban legends, everyone knows a friend of a friend who’s died from eating poinsettia on Christmas Eve.

The ghost story

The great inheritor of all this Yuletide terror was a bookish and very staid English academic called Montague Rhodes James, better known as MR James, the greatest writer of ghost stories in the English language.

James, who was born in 1862, became one of the most distinguished academics in Edwardian Britain – a medievalist who rose to be vice-chancellor of Cambridge University. When not writing treatises on the Anglo-Saxons, James had a sideline writing ghost stories to entertain his friends on winter nights. A ritual grew up among his circle which saw James read a new ghost story every Christmas.

Soon his ghost stories were published as anthologies in collections like Ghost Stories Of An Antiquary. The relationship between James and Christmas began to be really forged in the public mind in 1957 when BBC radio aired his short story Lost Hearts – which tells of murdered children returning to haunt the living.

By the late sixties, his stories were being adapted for television, and James became a regular dark fixture of the Christmas calendar and TV schedules.

If you haven’t read his stories, you must. There’s not a moment of violence, not a drop of blood spilled, but the tales are enough to have you scrambling for the nightlight. James’s skill comes in moments when something uncanny and supernatural is glimpsed from the corner of an eye at midnight, when shadows move, when a noise on the landing presages the arrival of something terrible in your home.

His most famous stories include The Mezzotint, where something strange is seen to move each night across the canvas of a painting; Oh Whistle, And I’ll Come To You, My Lad, in which an antiquarian foolishly summons something monstrous into the world; and Casting The Runes, where an invisible entity pursues anyone unfortunate enough to be passed a piece of paper containing ancient runic spells.

Children’s stories

Modern children’s Christmas stories, while not as pitch black as many of the tales we’ve discussed, can still be pretty bleak. Take CS Lewis’s The Lion, The Witch And The Wardrobe. It’s an unsettling read for children.

We find ourselves through the wardrobe with Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy in the land of Narnia, where it’s forever winter but never Christmas. Father Christmas has been banished by the magic of the White Witch – a crueller, more murderous version of Hans Christian Anderson’s Snow Queen. She kidnaps and drugs children and she plans to murder Aslan – a barely disguised Christ-figure.

It does all end happily ever after, but by the time it’s over, the kids reading the book have certainly been put through the emotional wringer, and it’s been made clear that Christmas isn’t just a time of fun and games but also a time when we need to fight and beat dark powers.

Then there’s The Snowman by Raymond Briggs. If you want dark and depressing, you’ve got it in spades. Even the book’s famous artwork is melancholy. The story tells of a little boy who builds a snowman which comes to life at the stroke of midnight. They fly over the land together and play, but when the boy wakes in the morning the snowman has melted. It may still make children cry, but it contains the ancient germ of the tales told around the fireside millennia ago by our ancestors – it’s essentially a story of death at winter.

Briggs once said: “I don’t have happy endings. I create what seems natural and inevitable. The snowman melts, my parents die, animals die, flowers die. Everything does ... It’s a fact of life.”

You could imagine a Stone Age storyteller saying the same thing 10,000 years ago.

Charles Dickens

You simply can’t write about Christmas without mentioning Dickens. Like Jacob Marley who forged in life the chains he wears as punishment in death, Dickens forged the modern Christmas we know today.

Dickens wasn’t just a great writer, he was a canny businessman. In 1840, Prince Albert married Queen Victoria and brought with him to Britain many of the customs of his native Germany – including the traditions of Christmas. Three years later, Dickens cashed in on the trend. He published A Christmas Carol in mid-December 1843, pulling together all the latest fads that were changing how Britain celebrated on December 25. Christmas trees, ghost stories, carol singing – these were all becoming woven into the tapestry of a British Christmas. The book was an instant bestseller.

No film has ever done justice to Dickens’s Christmas masterpiece. The short novel is truly creepy, and obsessed with death and darkness. The world of Scrooge is cold – the weather freezing most of the time. It’s nearly always night-time. The thought of food is on everyone’s mind. The dead are with us. Supernatural powers are waiting to claim our souls.

It’s as if all the worries and cares of our ancient ancestors huddling around their fires in forests thousands of years ago have been transplanted into the Victorian world and given life again in this novel.

The timeless tale

Professor Joseph Campbell was the greatest scholar of myths and legends who’s ever lived. His 1949 work, The Hero With A Thousand Faces, explores how all modern stories are deeply bound to the myths of the past. The idea is that without an ancient hero like Jason – of the Argonauts fame – there would never be a modern hero like James Bond. Such tales share myriad common traits across the gulf of time.

And so it is with Christmas stories. Without our ancestors spinning yarns on cold, fearful nights, hungry and afraid in the depths of midwinter, the Christmas story wouldn’t be what it is today.

Those dark and mysterious rituals which our ancestors took part in thousands of years ago – praying for the return of the sun at the end of the year, hoping that the light would finally vanquish the dark – they’re the real roots of the modern Christmas story.

And that’s as far removed from the EastEnders Christmas omnibus, a Wallace and Gromit cartoon, or a rerun of The Great Escape as you can possibly get.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel