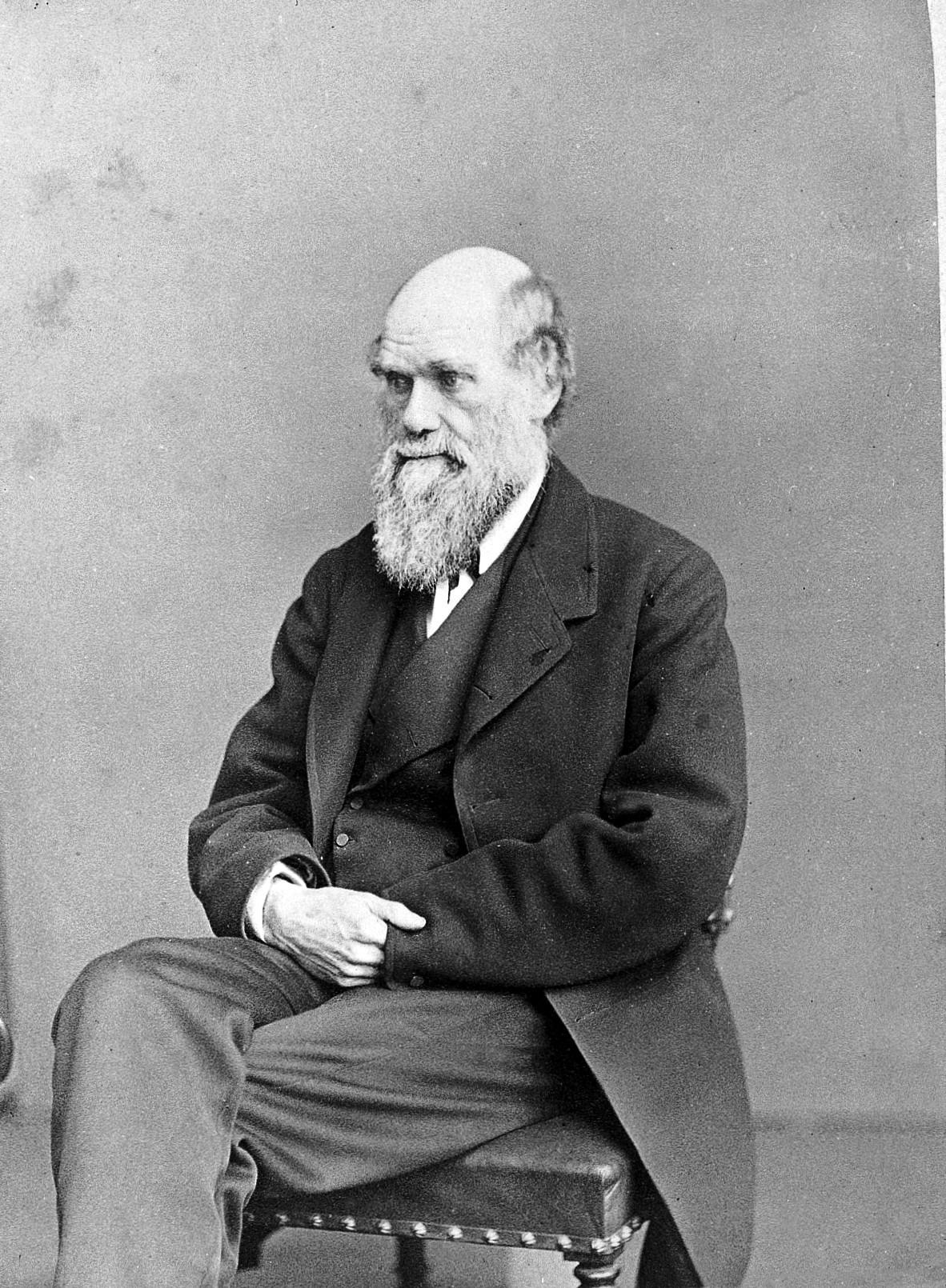

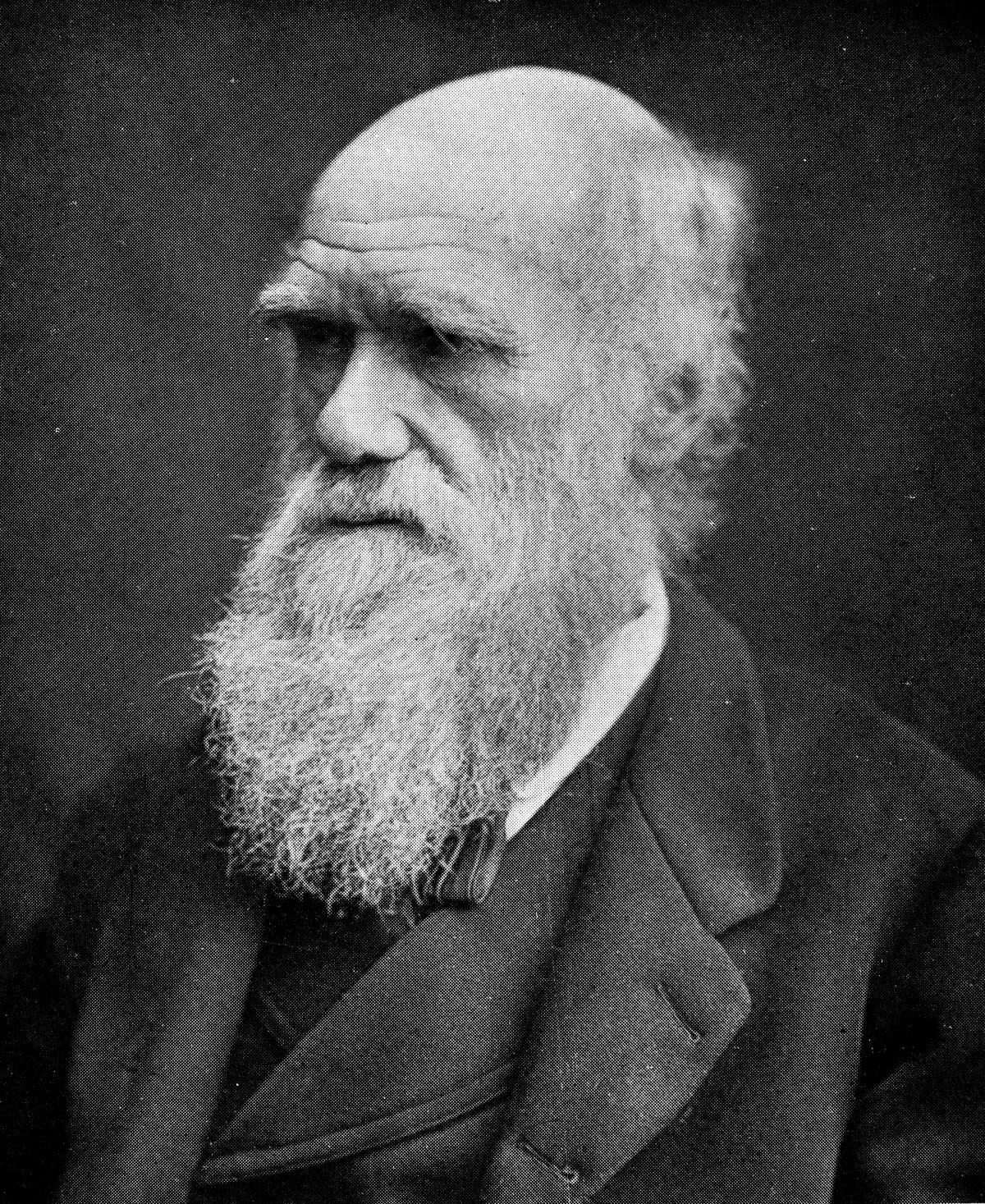

One was would become the father of evolution, the other destined for a tragic death. Sandra Dick finds a new book sheds light on a fascinating chapter in the life of Charles Darwin.

The young man who would become the father of evolution settled down to listen to his Edinburgh University lecture and was not terribly impressed.

In his opinion, Edinburgh’s powerful and acclaimed Professor of Natural History, Robert Jameson, was a rather dreary speaker. Charles Darwin, just 16 years old and following in his father’s and grandfather’s footsteps studying medicine at Edinburgh University, was bored.

“The old, brown dry stick Jameson,” complained Darwin. His lectures, he wrote, were “incredibly dull… the sole effect they produced on me was the determination never as long as I lived to read a book on Geology or in any way to study the science”.

It was 1825, Edinburgh was still flushed from the intellectual boom of Enlightenment and university lecturers wielded influence and power.

Criticism would not be welcomed, and definitely not by Professor Jameson, with a reputation to uphold and no time for cheeky upstarts – particularly one fearless student with an enthusiastic interest in expounding alternative theories to his.

Darwin, of course, went on to seal his place in the history books, seemingly airbrushing over any influences the city’s great minds may have had on his theories on the way.

However, the outcome for his fellow Edinburgh University student, the outspoken Henry H. Cheek, who shared his lack of enthusiasm for Professor Jameson, would end in tragedy.

Now the fascinating connection between Darwin, the unfortunate Cheek, Edinburgh’s powerful university community and a host of larger than life characters including infamous anatomist Robert Knox – whose dealings with murderers Burke and Hare would stain his name forever – has been explored in a book which unravels an extraordinary period in Edinburgh academic history.

In it, author Dr Bill Jenkins’ laborious research sheds light on Darwin’s brief but significant studies in Edinburgh, in an era when the dying embers of the Enlightenment were still igniting scientific thinking, and when some of the brightest minds were exploring ground-breaking ideas on evolution and natural history.

Although Darwin’s time in the capital city was fleeting – he quit after two years going on to airbrush the period from his life’s work - Dr Jenkins concludes there can be little doubt that feverish debates surrounding the transmutation of species that swept drawing rooms, lecture halls and student gatherings laid the foundations for the scientist’s theories and his work, Origin of Species.

And he uncovers a remarkable moment in time that unveils the cut-throat and often vicious academic world behind one of the world’s great seats of learning, and the gulf that separated students cocooned by money, and those without.

“It is a bit like a soap opera,” says Dr Jenkins. “In many popular accounts of the theory of evolution the reader could be forgiven for coming away with the impression that evolution was largely invented by Charles Darwin between his return from the famous voyage of the Beagle in 1836 and the publication of the Origin of Species in 1859.

“Nothing could be further from the truth.

“It also makes you wonder what the unfortunate Henry Cheek may have achieved if he had had the chance to be successful.”

Darwin and Cheek both attended Edinburgh University’s medical school in the mid-1820s, when the intellectual explosion of Enlightenment was still fresh.

It was some 35 years before Darwin would pen Origin of Species, however Edinburgh was a fertile ground for radical thinking, compounded by strong links with Paris where theories on transmutation of species were being explored and shared.

While Edinburgh’s reputation as a medical school was unrivalled, private anatomy schools run by the likes of the flamboyant Robert Knox ran alongside, filling gaps in certain professors’ lack of knowledge and competing for students’ cash.

According to Dr Jenkins, the squeamish Darwin found some lectures hard to stomach, and fellow student Cheek, fiercely intelligent but from a relatively modest background, shared his downbeat feelings concerning Professor Jameson.

“A lot was to do with Jameson’s role as Keeper of the Museum. If students wanted to use specimens, it was down to him. And if he didn’t like the look of them, he wouldn’t let them in,” explains Dr Jenkins.

“Cheek loathed him and said so quite loudly.”

While Professor Jameson followed Neptunism, and the theory that the earth’s rocks were formed by the receding primordial ocean, Cheek absorbed exciting new theories and shared them in robust debates at The Plinian Society where Darwin was also a member.

But it was his move to launch a rival scientific journal, the Edinburgh Journal of Natural and Geographical Science, that would goad his Professor and kickstart his own downfall.

The journal included views of, among others, private anatomy school lecturer, Robert Knox, a highly engaging speaker whose path was yet to cross that of the notorious murderers, Burke & Hare.

Cheek’s decision to use his journal to chastise Professor Jameson's control of the university museum and decry his lectures as “only calculated to delude”, was disastrous.

“Cheek set himself up as a rival to Professor Jameson even though he was just a student,” adds Dr Jenkins.

His obstreperous behaviour was soon publicly slapped down by the professor’s outraged supporters. But the city would become divided between those who supported Cheek, and the professor’s far more powerful connections.

There would be only one winner.

Wings clipped and character smeared by the run in with authority, Cheek left Edinburgh in 1832. Perhaps unable to afford to spend time exploring new theories of transmutation, he started work practicing medicine in Manchester.

But within a year, he had taken his own life.

A eulogy written by his friend described him as “a young man of gentlemanlike feeling and most zealous talent”, who found that “to meddle with science was to be expelled from all fraternity in the profession.

“The effect upon his mental constitution was so great, that he never recovered the shock, and shortly afterwards withdrew himself – by a sad, self-inflicted death – from a world he appears to have been unfitted for.”

Darwin, meanwhile, had moved on. In later writings he would largely dismiss Edinburgh’s impact, instead portraying his ideas and theories as entirely original.

Even time spent exploring the Forth shoreline with another Edinburgh University Professor, Robert Grant – who, like Cheek, was also inspired by new theories of transmutation – was skimmed over.

“Because Darwin is Darwin, people tend to take him at face value. He downplays the influence of people like Robert Grant and implies he didn't pick up any ideas in Edinburgh.

“The reputable way of working at that time was to collect evidence and facts and let the truth emerge from what you find, not build great castles in the air of theory and try to prove whether they are right or not.

“That is how Darwin wanted to present his work, and not say he got his ideas in Edinburgh.

“But there’s a huge amount of circumstantial evidence that Edinburgh had a greater influence on him then he was prepared to admit.”

Meanwhile, Cheek’s enthusiasm and potential was crushed both by his bruising time at university and his lack of wealth.

“Darwin was from a wealthy family, a man of independent means who didn’t have to work and could spend time working on his theory and raising a huge family.

“But Cheek had to work for a living,” adds Dr Jenkins.

“Part of the reason Darwin became the father of biology, was that he was fortunate enough to devote time and energy to do it, rather than struggling to pay the rent.”

Evolution before Darwin by Dr Bill Jenkins is published by Edinburgh University Press.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel