Edinburgh's botanic garden is 350 years old. Sandra Dick looks back on how the garden has grown.

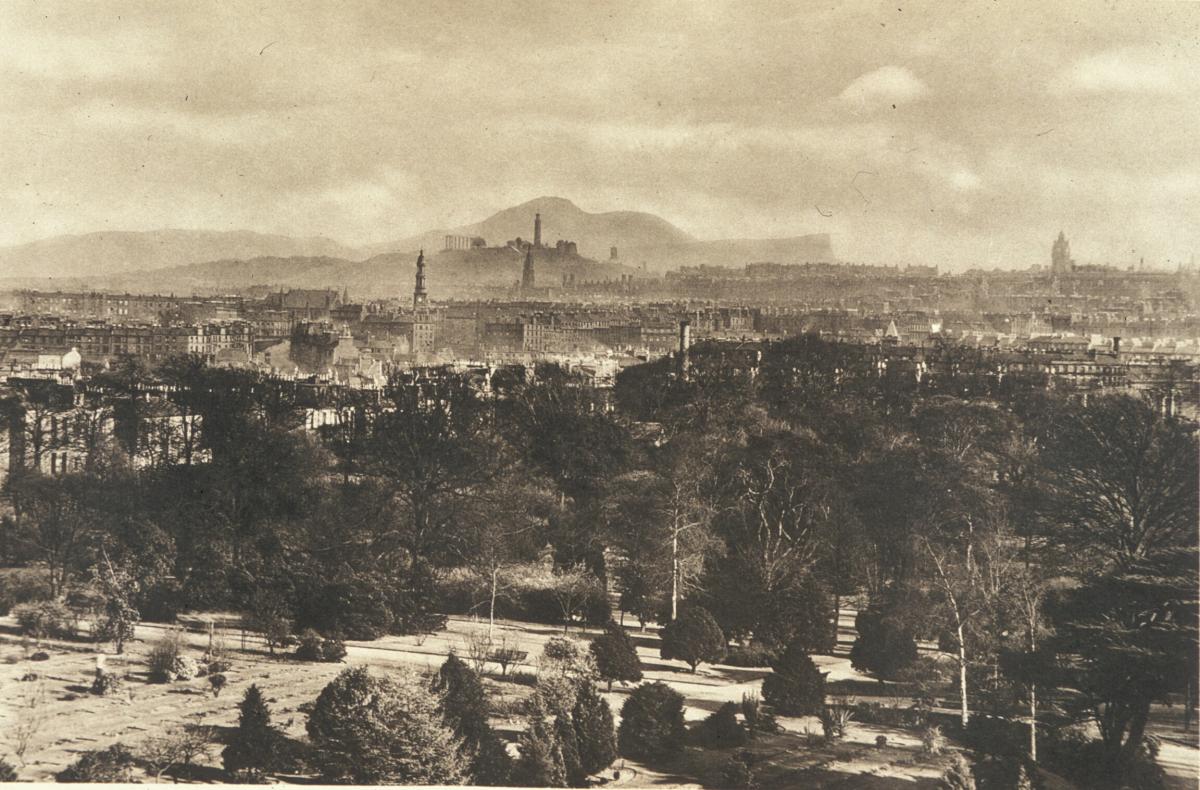

It was the age of the bubonic plague, when Edinburgh’s citizens lived tightly confined within its city walls, what would become Princes St Gardens was a noxious swamp and memories of Cromwell’s army were fresh.

Life for most was dire. Disease and illness rampaged through the Old Town’s cramped tenement buildings that towered up to a dozen storeys high. Where tourists today admire quaint closes and cobbled lanes ran an open drain choked with raw sewage, dead animals and stinking waste.

For those in search of a cure for ailments and complaints, there were often only the stark options of visiting the nearest quack for a concoction probably consisting of spiders’ webs, spawn of frogs, juice of woodlice and gizzard of hen, or of simply suffering.

Dank, destitute and deprived, yet amid the stench and misery would sprout a tiny garden where herbs, flowers and plants with healing properties burst with colour and thrived, and where the roots for one of the world’s greatest botanic gardens were taking hold.

From those small shoots 350 years ago emerged today’s Royal Botanic Garden of Edinburgh, and a love affair with the natural world that would see its intrepid botanists and plant explorers cross deserts, climb mountains and carve their way through thick jungle in search of precious blooms, shrubs, towering trees to the tiniest of plants to bring home to Scotland’s capital.

On Tuesday, full details of how the RGBE plans to mark its very significant birthday will be revealed. Included in the celebratory agenda is a reception in the Garden Lobby of the Scottish Parliament later this month – by coincidence, a spot within a stone’s throw of where it all began in 1670.

According to Simon Milne, Regius Keeper, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, the birthday celebrations will be “an opportunity to celebrate a great Scottish success story and to invest in the future of this world-leading and internationally respected institute”.

It certainly comes at a time when the RBGE’s scientific work is particularly relevant; with the world’s plants and pollinators under threat from climate change and habitat destruction, and some rare species dependent on the Gardens’ experts for their very survival.

All of which is a long way from the dark days of 1670, when the world of plants and their potential healing powers were still being slowly unravelled.

Knowledge of some plants’ medicinal properties had existed for centuries but as two medics, Robert Sibbald and Andrew Balfour realised, Scots’ abilities to fully harness botanical cures and administer treatments in a consistent manner was far behind that of their Continental counterparts.

They had met while travelling in Europe. Despairing of Scotland’s backward approach, they returned to create Scotland’s first physic garden on a modest patch of ground little bigger than a tennis court, close to the Palace of Holyroodhouse.

The plan was to grow fresh plants for medical prescriptions and to help teach medical botany to students. With help from local physicians prepared to help with the costs, they began to culture and import foreign plants to the city.

Soon, however, their garden had outgrown its tiny space. A new site was found where Waverley Station now stands, but the 1689 Seige of Edinburgh resulted in a burst dam at the east end of the Nor Loch, the Garden flooded and specimens were lost.

A new site on a ‘green field’ site alongside Leith Walk was established and there, under the inspirational leadership of Dr John Hope and with an endowment from the Crown, flowers and plants – including bananas, tea and coffee plants - blossomed, along with the nation’s great minds.

The Scottish Enlightenment saw the Garden and its botanic classrooms became a key player, helping to inspire new thinking and stimulating discussion of a world far beyond the city’s boundaries.

Not surprisingly, it would not be long before the Garden once more outgrew its surroundings – heralding one of the most remarkable episodes in its long history.

A new location was found two miles away in Inverleith. The site was plucked clean of weeds by an army of women and children, the trouble, though, was how to uproot thousands of trees and plants and transport them to their new surroundings?

Today - traffic and roadworks permitting - the journey from Leith Walk to Inverleith should take less than ten minutes by car.

But in 1820, it involved the construction of a huge wheeled tree-planting machine big enough to contain six tonnes of tree, roots and soil, tied with rope, lifted by brute force and lowered on to a wooden cart to be pulled by six horses.

Each tree travelled across town at a snail’s pace over cobbled streets on a journey that took around three days. Indeed, moving the entire Garden took three years, yet there was barely a single specimen lost.

The Inverleith Garden expanded with a new tropical palm house – the tallest in Europe at the time – taking up its 70 acres site to accommodate exotic, unusual and scarce plants found and carefully transported home by the RBGE’s plant hunters.

Best known was George Forrest, who set off in 1904 on countless journeys to the Far East where he collected species including Primula, Lilium, Meconopsis and established RBGE’s international renowned Rhododendron collection.

Over nearly three decades, he introduced more than 10,000 specimens and laid foundations for links with China which have spanned over a century.

Today, in partnership with Kunming Institute of Botany, RBGE has a field station in China and works in around 35 countries around the world with the Himalayas, South East Asia and Central and South America all key areas for research and conservation projects.

Remarkably, on average the Garden describes one plant per week as new to science, mostly from the RBGE tropical team, while the Herbarium now contains around three million preserved specimens which are used for research purposes.

From a small garden intended to provide medicinal support to Edinburgh’s citizens, the RBGE became a learning establishment for doctors, a giant canvas for botanical artists, a botanical library, a wildlife oasis in the heart of the city and, increasingly, a centre for plant conservation.

It has even spread its wings to establish three further Gardens: Logan Botanic Garden near Stranraer which thanks to the Gulf Stream is home to exotics rarely seen in Scotland; Dawyck Botanic Garden near Peebles which features the world’s first Cryptogamic Sanctuary for the study of fungi and Benmore Botanic Garden near Dunoon, known for its monkey puzzle trees.

Mr Milne adds: “There are so many things that make the “Botanics” special.

“Our impactful and innovative plant research that addresses some of society’s biggest challenges – namely biodiversity loss and climate change; our education programmes that inspire and train the next generation of leading botanists, conservationists and horticulturists, and of course the National Botanical Collection – four gardens, an herbarium and our library and archives – a global resource of enormous significance that has its origins in the 17th century.

“I take particular pleasure in seeing families and diverse community groups, smiling and laughing as they visit our gardens and participating in our events and delighting in our exhibitions.

“It’s also immensely satisfying seeing threatened species propagated and grown in the Botanics and reintroduced to the wild - from Hong Kong to the Cairngorms.

“But what makes the Botanics really special is people; the staff and volunteers who through their passion, expertise and commitment make the Botanics thrive: radiating creativity and dynamism, and maintaining the momentum built up over 350 years by our equally committed predecessors.

“Our 350th anniversary in 2020 is an opportunity to celebrate a great Scottish success story and to invest in the future of this world-leading and internationally respected institute, including the Edinburgh Biomes programme that will protect the Botanic’s unique plant collections for future generations.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here