Does political murder change the course of history? After the US drone strike on Iranian general Qasem Soleimani, Writer At Large Neil Mackay explores what happens in the wake of an assassination

THROUGHOUT history assassinations have been mostly grubby murders which change little, if anything, politically. Only a few acts of political murder ever shaped the world in any meaningful way.

Scotland’s most infamous act of political killing – the assassination of James I – is a perfect example. It was tawdry butchery which had little lasting impact on the future of the country.

As the reign of his father, Robert III, came to an end, family intrigue put young James at risk as heir to the throne. En route to France and safety, James was captured by pirates and handed over to the English king Henry IV. He remained a hostage for 18 years but became close to English royals. He returned to Scotland in 1424 but his rule was fractious.

In 1437, conspirators attacked James and his English wife, Joan, in Perth. James tried to escape but was trapped in a sewer and knifed to death. His wife, though, fled, and their six-year-old son was crowned James II a month after the assassination.

By contrast, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria by Bosnian nationalist Gavrilo Princip on June 28, 1914, led directly to the outbreak of the First World War.

Today, the world’s attention is focused on another assassination – the killing of Iran’s General Qasem Soleimani on the orders of President Donald Trump. Will it be a meaningless killing that changes little and which the world quickly forgets, or will it shape the course of human history?

Only time will tell. But understanding what caused some of the most notorious acts of assassination in history, and the effects of those killings, might help us hazard a guess at what the future holds when it comes to the consequences of the Soleimani killing.

Brother versus brother

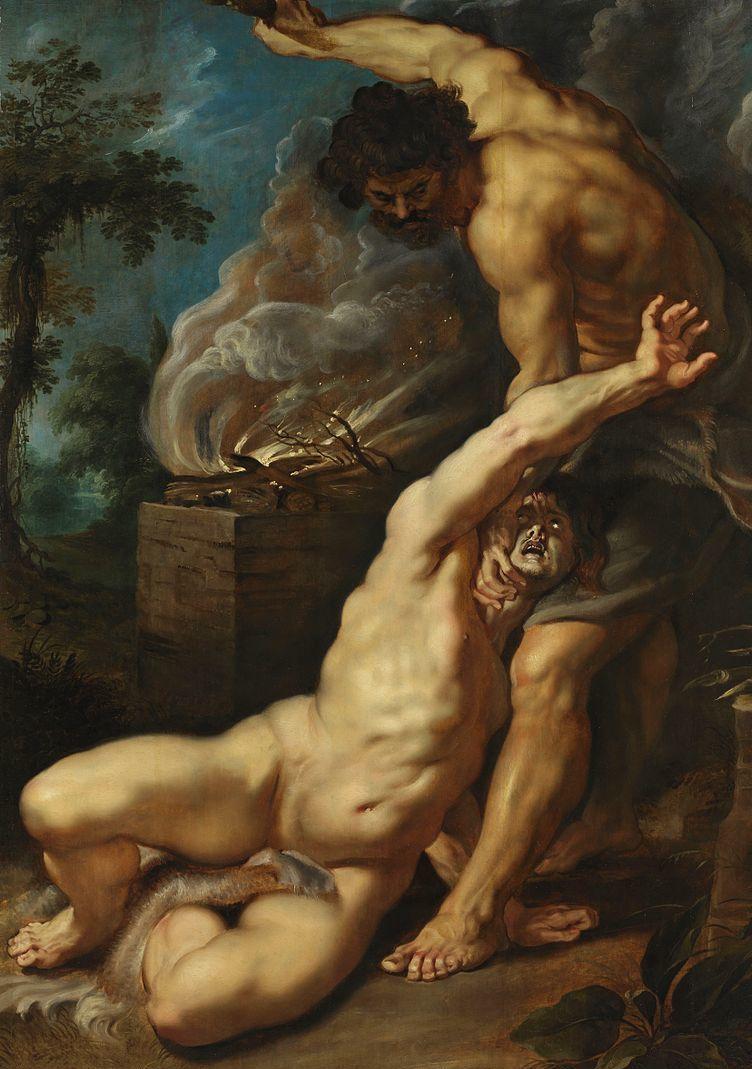

Let’s start at the beginning. Cain and Abel can be seen as a political killing. Biblical scholars and anthropologists now think the story might hold clues about the deep past of human history. Cain was a farmer, Abel was a shepherd. When the pair made offerings to God – Cain with crops and Abel with lambs – it was Abel’s gift which pleased God. Cain felt slighted and murdered his brother, and was cast out from society.

Some scholars suggest the story is symbolic of the violent clash between nomadic herdsmen, like Abel, and a new breed of people – stationary farmers who had developed agriculture, like Cain. Agriculture led to cities and monarchy. So, this story of fratricidal assassination may tell of one of the most significant, but unrecorded moments, in human history: the shift from a hunter-gather lifestyle to civilisation as we know it.

Biblical beheadings

The Bible also contains the story of one of the most daring assassinations ever – the killing of the Assyrian military commander Holofernes by the Jewish heroine Judith. Of course, as with much in the Bible there’s no proof it happened – nevertheless the story marks one of the first accounts of assassination having direct consequences on the political world.

In the story, the Assyrians, led by Holofernes, are terrorising the Israelites. Judith, a beautiful widow, goes to the Assyrian camp and charms Holofernes, getting him drunk and promising him intelligence on the Israelites. Holofernes passes out and Judith cuts his head off. The Assyrians flee and Israel is saved.

Knives out in Rome

The most famous assassination in history came in 44BC when conspiratorial Roman nobles stabbed Julius Caesar to death. Caesar had been named “Perpetual Dictator” just a few months earlier and it seemed the Roman Republic was about to end. How much the assassination really changed ordinary Roman life is debatable, but it ensured that Caesar was on the winning side of history even in death. The doomed republic wasn’t saved. Caesar’s heir, Augustus, became the first emperor. All emperors, from then on, would be known as Caesar.

Assassinations of emperors became routine. With each political murder little changed substantively. Over 500 years, some 20% of Rome’s 82 emperors were assassinated. Caligula was only the third emperor to rule. His reign was one of cruelty and sadism. Eventually, his own bodyguard cut him to pieces. Caligula was succeeded by his uncle Claudius – who was probably assassinated by his wife Agrippina so that her son Nero could assume the title. Agrippina in turn was eventually killed on the orders of Nero.

Killer gangs

Rome also prompted the creation of one of the first assassin organisations in history – the Sicarii, a word which today lends itself to the Latin American term sicario, a drug cartel hitman. The Sicarii were Jewish rebels fighting the Roman occupation of Judea, and they perfected the art of close-up killing of high-profile targets in broad daylight.

The spirit of the Sicarii lived on in the organisation which gives us the word assassin – the Islamic secret society known as the Hashashiyan. The name most likely derives from hashish as followers of the organisation are said to have used the drug. This order of assassins was set up around 1090 and would spread terror among European Crusaders, striking at will from mountain fortresses in Persia and Syria. They were masters of guerrilla warfare, and political murder.

The original assassins were similar to the medieval Japanese Ninjas, also known as Shinobi. The first ninja was the semi-legendary Prince Yamoto Takeru who dressed up as a beautiful young female servant to get close to two targets he intended to assassinate. In Japan, such tactics were seen as dishonourable and beneath the dignity of Samurai knights.

Religious murder

In Europe, the medieval era was a time of Christian zealotry and conflict so it’s no surprise that assassination in the Middle Ages took on a distinctly religious flavour. Henry III of France was killed by a fanatical monk in 1589, and Henry IV of France was killed by what we would today term a Catholic “terrorist” in 1610 after numerous failed assassination attempts. The Dutch protestant Prince of Orange, William the Silent, was also killed because of his religious beliefs, shot in the chest at close range by a French Catholic, Balthasar Gerard, in 1584.

Gerard’s execution was particularly gruesome: his hand was burned off, the flesh torn from his bones with pincers, he was quartered and disembowelled alive, his heart was torn from his chest and flung in his face and finally he was beheaded. The execution came after days of torture. Of course, despite these assassinations shaking the foundations of Europe, they altered little the course of the continent’s wars and religious conflicts.

The most infamous religious assassination of the medieval era took place in England, with the murder of the Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas à Becket in 1170. Becket had been a friend of King Henry II before he took office. Henry wanted the monarchy to have more control over the church, but when Becket became Archbishop he supported the Pope.

An infuriated Henry was overheard by a number of loyal knights saying of Becket: “Will no-one rid me of this turbulent priest?” The knights took it upon themselves to butcher Becket inside Canterbury Cathedral – an act so blasphemous it shook European society to its core. Becket became one of England’s most important saints and Henry had to humble himself before the church in penance. In the wake of the assassination, nothing substantively changed in terms of the relationship between the church and monarchy in England.

Elizabeth I was subject to plenty of assassination plots during the troubled religious period she ruled, but it was her successor James who survived perhaps the most audacious assassination plan in history – the 1605 Gunpowder Plot. If Robert Catesby, Guy Fawkes and the rest of their Catholic conspirators hadn’t been caught, the assassination would have taken out the entire government. Instead, the plot was foiled, the rebels executed, and the rights of Catholics were even more restricted than before. It took a further 200 years before the coming of Catholic emancipation.

Political killing grows up

The modern era made political murder much easier. Assassins didn’t need to get up close and personal to their heavily guarded targets, thanks to bombs, bullets, and sniper rifles.

America perfected assassination as the art of politics via murder. Four presidents died at the hands of assassins. Abraham Lincoln was killed by the Confederate extremist John Wilkes Booth – shot at point blank range in the head in 1865. President James Garfield was killed by a mentally ill assassin, and William McKinley by an anarchist.

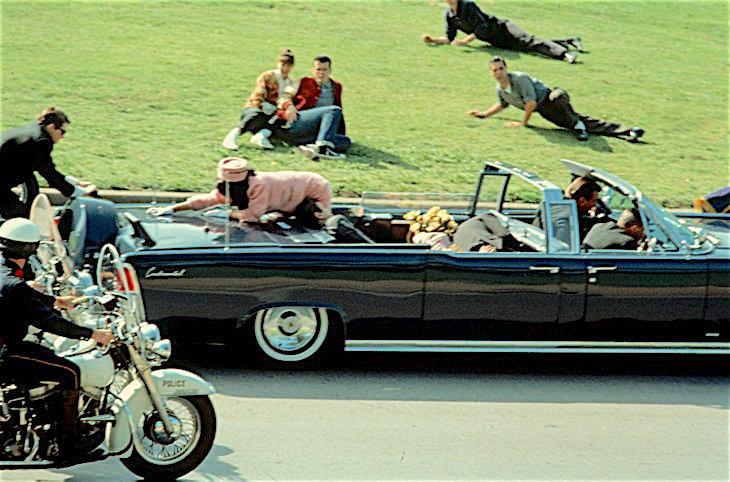

The assassination of John F Kennedy in 1963 ushered in a new era of political murder in America, which saw leaders deemed as the brightest lights of the progressive movement killed in cold blood. Bobby Kennedy followed his brother to the grave when a Palestinian gunman, Sirhan Sirhan, shot him dead while running for the Democratic nomination for president in June 1968. The killer was motivated by Kennedy’s support for Israel.

A few months before, civil rights leader Martin Luther King was killed by a sniper at a Tennessee motel. James Earl Ray was eventually convicted of the assassination, but many believe Ray didn’t act alone and there was a conspiracy to kill the man who represented the hopes of African-Americans.

These killings certainly scarred American society, but did they change American politics? Kennedy’s successor Lyndon Johnson, for example, stuck to a political programme pretty similar to JFK’s, and the civil rights movement didn’t lose momentum with King’s death. However, Bobby Kennedy’s assassination probably did change the course of history. Would he have taken the Democratic nomination and beaten Republican Richard Nixon, who won in 1968? Many think yes. No Nixon, no Watergate.

Throughout the 20th century world leaders fell like ninepins to assassins’ bullets, with India almost as traumatised by political murder as America. Gandhi, the father of the Indian nation, was murdered by a Hindu extremist in 1948. India’s first female prime minister, Indira Gandhi, was assassinated by Sikh extremists in 1984. Her politician son, Rajiv, was also killed in 1991.

Soon it seemed no leader was safe – not even the Pope. A Turkish hitman opened fire on Pope John Paul II in 1981.

Britain has only lost one prime minister to an assassin’s bullet – Spencer Perceval who was shot by a disgruntled businessman in 1812. However, the UK has lost plenty of top politicians to assassins. The Irish National Liberation Army killed the Conservative MP Airey Neave, a close friend and mentor of Margaret Thatcher, with a car bomb at the House of Commons in 1979. The same year the IRA killed Lord Mountbatten with a bomb in his fishing boat. Mountbatten was the uncle of Prince Philip, former chief of defence staff and the last viceroy of India. In 1984, the IRA’s Brighton bomb attack killed five including Sir Anthony Berry MP. These audacious killings all hardened Thatcher’s determination to defeat the IRA and led to the intensification of the Northern Ireland Troubles.

Wartime assassination

Of course, Irish republicans argued that they were at war and British leaders were so-called “legitimate targets”. It is during periods of conflict that assassination comes into its own and produces some of the most spectacular acts of political violence the world has seen.

During the Cold War assassination was part of the toolbox. The CIA infamously plotted time and again to assassinate Cuban leader Fidel Castro. Bulgaria’s version of the KGB assassinated defector Georgi Markov in the middle of London, with a stab from a poisoned umbrella tip. Britain and Russia plotted to kill Hitler during the Second World War, and MI6 trained the Czech commandos who assassinated one of Nazi Germany’s most brutal leaders, Reinhard Heydrich, architect of the Holocaust.

Today, Russia assassinates enemies of the Kremlin whether they are Chechens targeted abroad, or dissident spies like Alexander Litvinenko poisoned with polonium in London. Israel has also long used assassination as part of its military and foreign policy, most famously in the wake of the Munich Olympics massacre. After the Palestinian terror group Black September killed 11 Israeli athletes in 1972, prime minister Golda Meir authorised Operation Wrath of God which assassinated targets connected to the atrocity wherever they were.

These assassinations in the midst of conflict mostly hamper enemy operations, weakening their leadership and draining resolve and resources, rather than significantly altering the course of the conflict. The killing of Markov didn’t end the Cold War, it embarrassed the West. Heydrich’s death didn’t defeat Nazism or slow the Holocaust. Operation Wrath of God didn’t end conflict between Israel and Palestine.

And so we come full circle to the death of General Qasem Soleimani. All we know is that there will be consequences, but what they will be it is too soon to say. It could drain American power in the Middle East. It could increase the strength of Iran. It could spark a regional conflict. It could seriously hamper the fight against Islamic State. It could also lead to renewed negotiations, and a slim chance of a thaw in relations.

We don’t yet know if we’re living through a moment like the murder of James I which changed little about the world, or a moment like the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand which changed everything.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel