With fear of the coronavirus uppermost in the minds of the world’s most eminent scientists, Writer at Large Neil Mackay explores how mass outbreaks of disease have fashioned the world around us

THE outbreak of the coronavirus in China poses one huge and terrifying question: are we heading for a full-scale pandemic?

The World Health Organisation has declared the outbreak a global emergency, and the coronavirus has already come to the UK.

So far, there have been nearly 10,000 cases in China with at least 213 deaths. The virus has spread across the Far East, and made it to France, America, Canada, India and Finland.

Pandemics – defined as diseases which spread rapidly over a large area of the planet – aren’t just killers which claim the lives of millions. The death toll, the panic, and the grief unleashed by pandemics fundamentally reshape the societies they ravage.

Our best modern example is HIV/Aids which has killed around 32 million people worldwide. The disease reshaped how the world talked about sex, and caused a revolution in medicine. Cholera brought about advancements in public sanitation.

Here we look at some of the most virulent outbreaks in human history, and unravel why they happened, and how they changed the face of history, society and culture.

The plague of Athens

The history of the Western world would have been very different if it weren’t for an outbreak that turned the city of ancient Athens into the set of an apocalyptic horror movie.

To the ancient Greeks, the Peloponnesian War between Athens, the seat of democracy, and the militaristic state of Sparta, was the equivalent of the First World War. It was a titanic struggle between two superpowers and it engulfed the entire Greek world.

When the war began in 431BC, the Athenians, a naval power, knew they would be outmatched on land against the fabled Spartan army. So under the command of their famed leader Pericles, the people retreated within the walls of the city. The plan was to allow the Athenian fleet to grind down the Spartans.

The city was overcrowded with refugees from the countryside, and supplies were flooding in from across the Mediterranean to the Athenian port of Piraeus to keep the people fed.

In 430BC, a “plague ship” – carrying probably either typhoid or typhus – entered Piraeus unbeknown to the port authorities. Soon 100,000 people would be dead – at least one-quarter of the city’s population.

Chaos broke out in the city. The ancient historian Thucydides wrote in his History of the Peloponnesian War: “The catastrophe was so overwhelming that men, not knowing what would happen next to them, became indifferent to every rule of religion and law.”

The rich blew their money before they died. The sick were left unattended for fear of contagion. The bodies piled up. The people believed the Gods had abandoned them. Nobody was safe. Pericles himself died, leaving the Athenians rudderless. The plague returned twice more. Spartans watched while disease destroyed their enemies.

Sparta was eventually victorious, and the Athenian empire entered terminal decline – with it, democracy would soon be stifled. Who knows how the future of Europe might have been shaped if plague had not come to Athens, and it was democracy which triumphed over Sparta.

The Antonine plague

It was early globalisation which turned the Roman Empire of the second century into a mass graveyard. Rome’s troops were besieging the Mesopotamian city of Seleucia, now found in modern Iraq, in 165AD when illness began to sweep through the ranks. Roman legions were made up of soldiers recruited from across an empire which spread from Hadrian’s Wall to Syria.

Troops returning from Seleucia to their homelands brought the illness with them. It’s thought the plague was smallpox. In Rome, the plague was killing 2,000 people a day. One in four people died in the city, and across other areas the mortality rate was one in three.

The entire world had a population of around 200 million at this point. It’s thought that the plague claimed five million lives in Europe and the near east. The plague may even have spread to China.

The outbreak claimed the life of Emperor Lucius Verus. He had co-ruled with Marcus Aurelius Antoninus – who had the misfortune to find the plague named after him. The plague fatally weakened the Roman Empire, crippling the army, and disrupting trade and commerce.

When the illness hit what is now Germany, it brought refugees fleeing the plague south, piling pressure on the borders of the empire. It would be “barbarian” tribes which eventually brought Rome to her knees.

The virulence of the plague is thought to be down to the fact that this was the first major incursion of smallpox into Europe and inhabitants had zero resistance to the illness.

A century later, from around 250AD, the Plague of Cyprian further exhausted the Roman Empire, also hastening its collapse. Named after St Cyprian, who witnessed the suffering, the outbreak seems to have begun in Carthage, in what is now modern Tunisia. Identification of that plague ranges from measles to ebola.

At the time, early Christians were made scapegoats for the disease, and persecuted and murdered. At its height, the plague killed 5,000

a day.

The plague of Justinian

By the reign of Emperor Justinian, the western half of the Roman Empire had collapsed. Justinian ruled in the east from the Byzantine city of Constantinople. But Justinian was ambitious, and planned to reunite and rebuild the shattered superpower.

However, in 541AD, the first recorded outbreak of bubonic plague – Yersinia pestis – threw the emperor’s plans into disarray. Constantinople became the epicentre of the outbreak.

At its height, the plague was said to have killed 10,000 a day in Constantinople alone, and claimed up to 40% of the city’s population. The plague could have killed up to 50 million people in total, during multiple bouts of recurrence. It is thought the disease came on grain ships, bearing rats that carried infected fleas, from Egypt.

Agriculture broke down as farmers died and there was no-one to till fields and raise animals. The tax base collapsed as there weren’t enough people alive to fill treasury coffers. Expansionist tribes like the Goths and Lombards began claiming chunks of the old western empire as their own. Some believe that the plague hit Britain particularly hard and allowed for the success of the Anglo-Saxon settlement of England.

The strain of bubonic plague which would devastate Europe in the 1300s was a distant cousin, it is believed, of the plague which ravaged the reign of Justinian.

The Black Death

Bubonic plague has long been with us. Evidence of Yersinia pestis has been found in skeletons up to 5,000 years old. But never has the plague had such a profound effect on history as the toll wrought by the Black Death between 1347 and 1351.

The plague swept from the Russian steppe and Persian gulf to the highlands of Scotland and north Africa. At the upper end of estimates, around 200 million people died. Europe’s population was cut by up to 60%, and about one-fifth of the entire world’s population was lost.

The Black Death came down the trade route known as the Silk Road from China and then hopped on ships travelling the Mediterranean and throughout Europe. No other illness has so radically altered the course of humanity. It changed everything from culture to commerce, from economics to politics.

In most major European cities about half the population died. Archaeologists are still discovering plague pits used for mass burials today.

European culture was highly developed in the 1300s, and writers and artists responded to the plague with works like The Decameron by the Italian writer Giovanni Boccaccio, which tells of a group of aristocrats who lock themselves up in a country villa to weather the duration of the plague. Works of art began to feature skulls and skeletons. Ordinary people joined the ranks of the Flagellants, who would beat themselves with ropes and chains in order to purge the sins which they believed had brought the plague down on them. In essence, society went mad.

When the plague finally burned itself out on the land, Europe had been changed forever. With so many workers and peasants dead, survivors were able to demand much higher wages than before, severely weakening the feudal system, creating more social mobility and an emerging middle class. In England, such changes almost led to civil war in the clash known as the Peasants’ Revolt.

There have even been claims by academics that the sheer number of dead brought about a cooling of the climate. Less human activity and more free land led to reforestation, which some believe contributed to the Little Ice Age.

Inevitably, in an age with little science, scapegoats were sought during the Black Death, and in Europe those blamed were the Jews. In Strasbourg in 1349, 2,000 Jews were murdered. The same year the Jewish populations of Mainz and Cologne were exterminated. As a result, many Jews moved to Poland, where a large population built up, until the Second World War and the Nazi Holocaust.

The Great Plague of London was the last major outbreak of bubonic plague to occur on the British Isles. It claimed 100,000 people, which was about one-quarter of the city’s population, between 1665 and 1666.

In September 1666, the Great Fire of London devastated the city. Many still think that the inferno brought an end to the plague. However, most scientists believe the plague had all but run its course by the time fire struck.

In the wake of the plague and the fire, London became the epicentre of a semi-Golden Age, with a flourishing of the arts and science as the city was rebuilt as a modern European capital.

The third pandemic

Science now refers to the events of 1855 which began in China as The Third Pandemic. If the first pandemic was the Plague of Justinian, and the second was the Black Death, then the outbreak of plague centred on Asia and the Far East in the mid-19th century is the third plague pandemic.

At least 12 million people died in China and India alone, but nearly all parts of the world were affected. The plague spread to Saudi Arabia, Egypt, San Francisco, Australia, Russia, the Caribbean, and South America. Officially, the outbreak lasted until 1960.

There was even an outbreak in Glasgow in 1900. It arrived in the Gorbals in August that year. Soon 35 were infected. Sixteen died. Rats were killed en masse in the city, even though it seems the infection in Glasgow was spread by human contact. Coins, trams and ferries were disinfected.

Patient Zero in Glasgow was a “Mrs B, a fish hawker”. The authorities found anyone connected to Mrs B, or who had attended her funeral, and quarantined more than 100 people. The Catholic Church supported a temporary ban on wakes following plague deaths.

Rapid industrialisation in China helped spread the virulent disease at its outbreak, as workers began moving across the country. This coincided with a period of social unrest which saw more movement of people – both troops and refugees – on a greater scale than before. In March 1894, the plague killed 60,000 in Canton in just a few weeks.

The plague soon spread to India where special measures were put in place to contain the outbreak by the British. Quarantine, isolation camps and travel restrictions were enforced by colonial soldiers. Indians found the conduct of Britain highly repressive and it helped fuel the desire for independence.

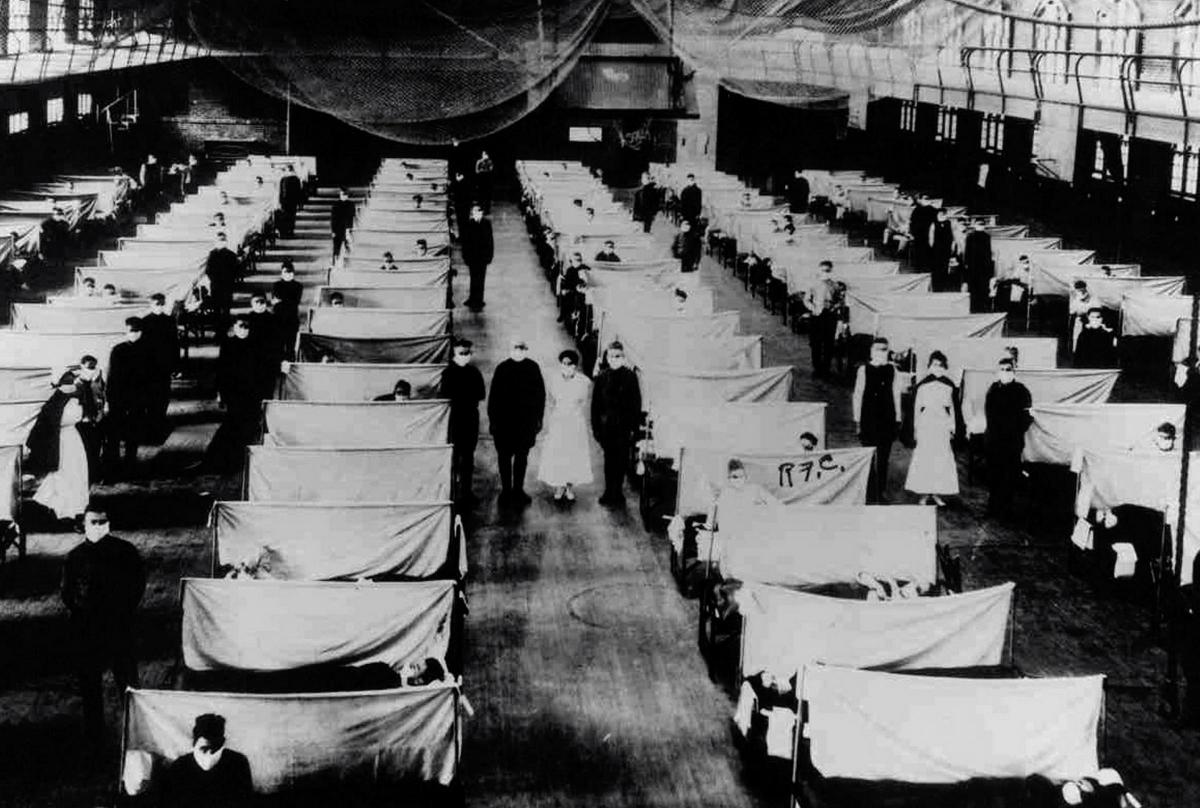

Spanish flu

The 20th century took all the contributory factors to the world’s previous pandemics and brought them together in one great confluence of bad luck and biology that became the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918.

War, globalisation, trade, transport – they all contributed to making Spanish flu, or the H1N1 virus, the most deadly outbreak of the 20th century.

The flu pandemic, which lasted until 1920, killed up to 100 million people – around 5% of the world’s population. Spanish flu claimed the lives of more people in 25 weeks than Aids killed in 25 years.

More people died from Spanish flu than in the First World War, which had an estimated death toll of around 40 million.

Science suggests that the possible epicentre of the outbreak was the Etaples military camp in France in 1917. Up to 100,000 soldiers passed through the camp each day. There was a hospital there, as well as a farm with pigs and poultry. Both animals harbour flu viruses which can mutate and jump to humans.

In the overcrowded conditions of the First World War, the contagion spread, moving among soldiers from dozens of countries. That’s when it went global, reaching even into the Arctic.

During wartime, newspapers in Germany, America, France and Britain censored material on the outbreak to keep panic low and morale high. The neutral nation of Spain was free to report as it pleased, and so many thought the outbreak had hit the Spanish hardest – thus the flu pandemic acquired its name.

With many soldiers badly debilitated by life in the trenches, the flu was able to claim many more victims than a “normal” flu. Spanish flu was made especially deadly as it hit out of winter season, was highly infectious and played havoc with the body’s immune system.

Although most flus kill the very young, very old and very sick, the elderly were partially protected from Spanish flu. A previous influenza pandemic – known as Russian flu – which hit in 1889/90, gave older adults partial immunity to the 1918 outbreak. So, in America, the vast majority of deaths were in the under-65 age range.

Victims had a bad death. There were cases of bleeding from the ears, and most deaths were down to pneumonia. At least 20% of those infected died, whereas “normal” flu kills about 0.1%.

There have been theories that Spanish flu aided the victory of the allies, and even helped speed up women’s rights, as so many victims were men. However, what it certainly did was set a template for what a modern pandemic looks like. It taught us that the one thing which imperils humanity is human activity. Transport, war, trade, travel – these are the things which the next great pandemic will exploit in order to spread and kill when it finally comes.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here