FIRST we had Ciara, now we have Dennis. Storm Ciara brought considerable chaos in its wake last week: hurricane-force winds and floodings, roads and rail lines closed, trees felled, domestic and international flights cancelled, householders left without electricity or water. Amber snow warnings were issued for parts of southern Scotland.

A section of a cafe and guest-house in Hawick gave way and collapsed into the fast-flowing River Teviot.

“It’s definitely the biggest storm in seven years and in terms of area affected it’s probably the biggest this century,” said Helen Roberts, a senior meteorologist at the Met Office.

Now Storm Dennis has been predicted to strike this weekend, though it is not expected to be as severe as Ciara.

As they shivered through Ciara last week, and turned up the heating and burrowed deeper under the duvet, older Scots could have been excused for recalling, even briefly, a major weather event that struck 52 years ago. Hurricane Low Q, it was called.

It occurred in the very early hours of Monday, January 15, 1968. It was, in the words of the Scottish journalist Ian Jack, who witnessed it, "probably modern Scotland's biggest natural disaster".

The front page of every newspaper in the country on the Tuesday morning related the scale of the hurricane. "20 dead, 1,000 homeless in hurricane", read the stark headline in The Glasgow Herald.

Gusts of up to 125mph were recorded in Dumfriesshire and 110mph on Clydeside. In Glasgow, nine people died. Two mothers and two of their young children were killed when a chimney head from an adjoining building crashed through their home in Dumbarton Road. Other people who were killed by falling masonry included a girl of five, and a Malaysian physiotherapist.

There were two deaths in Edinburgh, one in Cambuslang, one in Dumfriesshire. In the capital there were 800 calls reporting damage. Thirty-four people were moved out of a Leith tenement after a chimney stack crashed through a skylight and tore away part of the stairs, but four families on the top floor were trapped for five hours and had to be rescued by firemen using ropes and ladders.

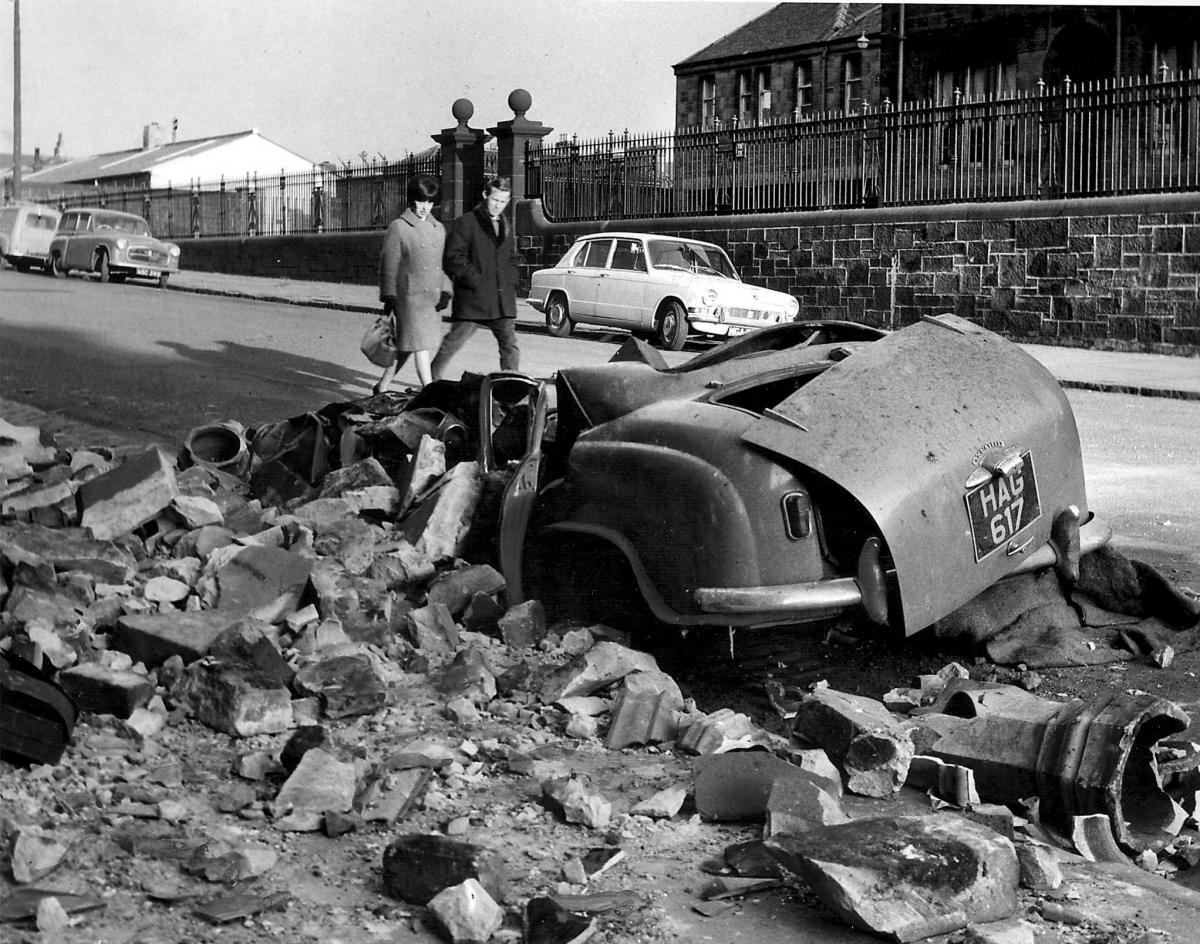

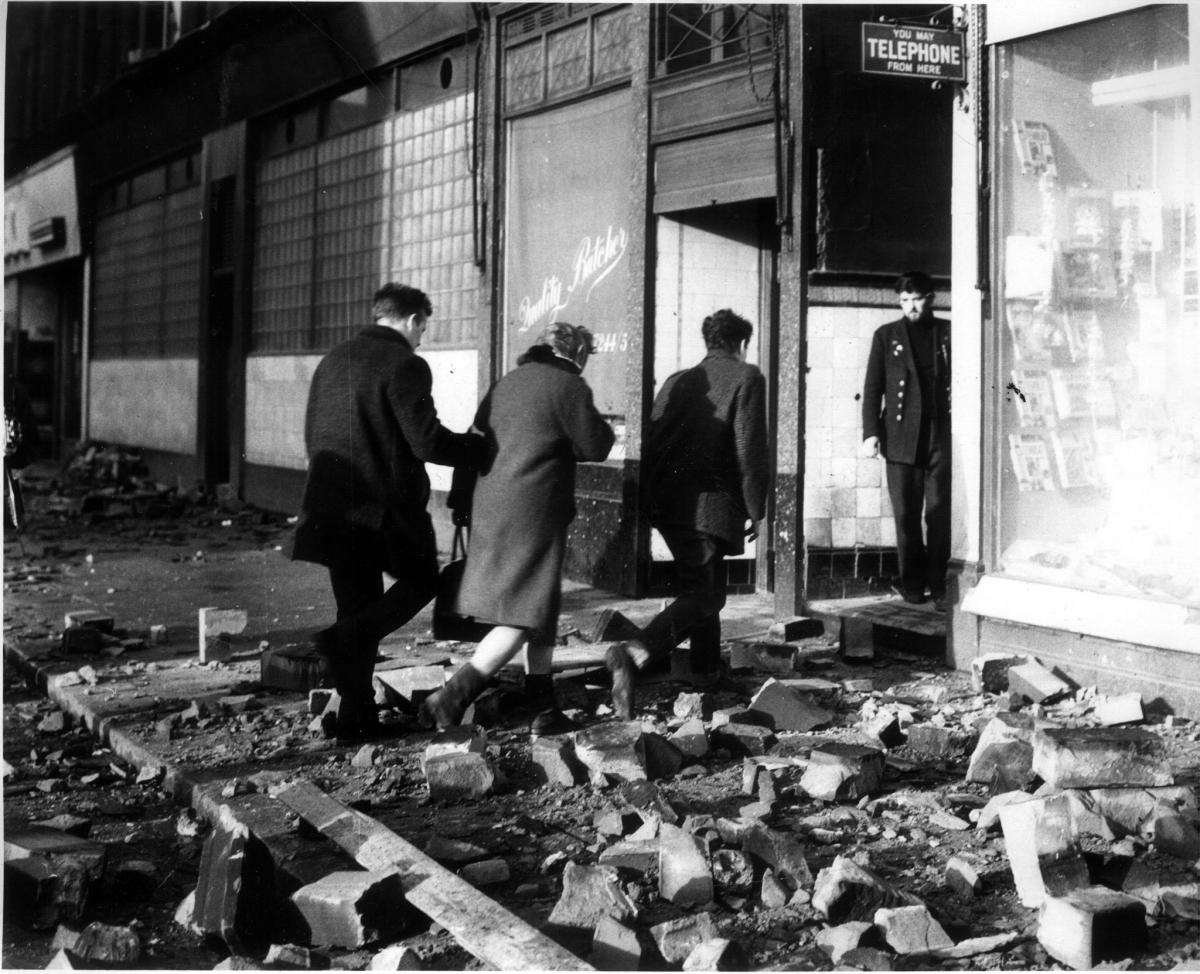

Photographs captured the chaos that had been caused by the storm: collapsed cranes and pylons, cars shattered by falling masonry, church spires lying broken on the street. One picture showed the gaping hole torn through a tenement, from top floor to bottom, that had been caused by a falling chimney-head. Glasgow police said the chaos had been worse than the Blitz.

As the clock ticked over from Sunday to Monday, Ian Jack was working the late shift at his then paper, the Scottish Daily Express, in Albion Street. He and his colleagues noticed that the windows began to rattle and thud, "as though an angry crowd were pounding on them". One or two of the windows began to crack and cave in.

"An office car delivered us home through a dark townscape or rolling chimney pots and flying slates", Jack recalled.

In all, 21 people died in Scotland as a result of the storm. Among them were three men who died when a dredger, the Cessnock, capsized off Greenock. The town was described as a battlefield. Garages and cars had been lifted by the unstoppable gusts of wind and deposited elsewhere. Between 2,000 and 3,000 local houses were seriously damaged.

A reporter on The Herald received a call from a 20-year-old Glasgow woman who was working as a nanny in Jericho, Long Island, New York. She wanted to know if her mother and her brother, who lived in the Gorbals, had been injured by the storm. By chance, the reporter had, two hours earlier, taken a call from the mother, complaining that her top-floor flat was being flooded by rain through a hole in the roof caused by a collapsed chimney-head; he was able to reassure the young woman that her family were uninjured.

As troops moved in to help clear debris from city streets, a handful of allegations of looting in evacuated, hurricane-damaged houses were reported to one Glasgow councillor. "These looters are lower than vermin", he said.

The website of the National Records of Scotland (www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk) says that Hurricane Low Q damaged a quarter of a million homes across the country, with almost 2,000 people becoming temporarily homeless.

Many thousands of properties were considered to be unfit for habitation or became irreversibly sub-standard in their condition, the records website adds. For over a year after the storm, a lack of workmen available to mend the damaged properties left families to live with tarpaulins over the holes in their roofs. The total cost of damage to property across Scotland was £30 million.

Had Hurricane Low Q been foreseen? The Herald reported on the 16th that the severity and range of the storm had been unexpected, although weather forecasters on the Sunday had warned of gales.

The cause of the devastation was a secondary depression, charted on Sunday, moving in a north-easterly direction towards the British Isles, the paper said, but it had been expected to pass over St Kilda and the Faroes. Winds in higher altitudes, however, had turned the depression in an easterly direction, and it kept deepening.

A forecaster at Glasgow Weather Centre said: "We knew there was a depression there and at 6pm on Sunday I forecast gales for the west coast of Scotland". Even so, The Herald noted, Low Q surprised everyone with its ferocity. And the emergency services were unprepared.

Politicians expressed their sympathies with those who had suffered. In the Commons on February 7, Ted Heath, then the leader of the Opposition, outlined the scale of the damage.

"The Secretary of State for Scotland has already told the House that the total damage in town and country is estimated at £25 million," he said. "It may well be that when the opportunity occurs to make the full calculation the damage will be seen to be greater. Certainly, the task of reconstruction following this damage is daunting.

"Therefore, I submit that this, alas, is a disaster on a national scale. It is a disaster beyond the resources of the people of Scotland to meet on their own. We in the rest of Britain would not wish them to do so, nor to face the consequences of a national disaster on this scale solely on their own resources.

"The consequences of Hurricane Low Q are all human problems", Heath added. "We can talk in terms of buildings – and, of course, much more than houses and tenements are involved; schools, churches, docks and factories are also concerned – or we can talk of stock, crops and timber. I found in the countryside, particularly in Stirlingshire, the feeling that there had been insufficient recognition of the damage which those who live in the country had suffered as a result of the storm."

Prof Esmond Wright, the MP for Glasgow Pollok, was not alone in pointing to the neglect suffered by the housing stock. The hurricane, he said, "seemed to blow wide open the whole policy of political and financial neglect, not only of Glasgow's housing but of Scotland's housing".

Shortly afterwards, he declared, "I am sure that very few hon. Members are not aware that every time one sails up the Clyde one meets the City of Glasgow 20 miles out, in that low cloud below which rests the grime and soot of two centuries of the industrial revolution. The red sandstone and grey sandstone buildings are paying the price for at least 70 years of neglect". Glasgow Govan MP Jon Rankin said that many of the tenements that collapsed were more than a century old.

Reading the coverage of the 1968 storm, one thing is of course noticeable by its absence: any mention of climate change. In that Commons debate, 'climate' gets one mention, courtesy of Prof Wright, who said there was "a problem of climate in Glasgow. There is a recurrent wind force of high velocity and at this time of the year it seriously handicaps existing private and corporation tenements. It is a tenemental problem".

Back then, there was no Greta Thunberg, of course, no Extinction Rebellion. Friends of the Earth had yet to be established. And yet, some warnings were being delivered: in 1968, as The Guardian reported two years ago, the Stanford Research Institute warned in a report that rising CO2 levels could, if left unabated, result in such "climatic changes" as melting ice-caps and rising sea-levels.

It would not be until 1975, the paper added, that the term 'global warming' appeared in a peer-reviewed academic journal; and it was in 1988 that Nasa scientist James Hansen warned US Congress that "global warming had begun".

Today, of course, we are all much wiser about the climate emergency. Documentaries, climate activists, news stories, footage of melting ice-caps, and authoritative accounts of the state of our oceans, all have brought home to us the perils we face. It is a message reinforced by such disasters as the bushfires in Australia, where rising temperatures have brought about hotter, drier conditions across the vast country.

In some quarters, there is a strong belief that the floods and gales witnessed last week were the "reality of the climate crisis".

Labour's Shadow environment secretary, Luke Pollard, said: “The reality of the climate crisis is that more extreme weather will happen more often and with devastating consequences".

Scientists, however, are more cautious. “With this exact storm it’s only just happened so it’s very hard to say if it’s climate change or not,” Kate Sambrook, climate researcher at the University of Leeds, told the i newspaper this week.

“But the research into Storm Desmond in 2016 shows that there is a human fingerprint on the storm and that they are being made more likely with climate change.”

“The bottom line is that climate change and with this warmer atmosphere we are going to see more extreme rainfall events like Storm Ciara and Storm Desmond in the future".

.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here