The monks of Papa Stronsay are preparing to welcome an influx of visitors seeking heavenly peace, finds Sandra Dick.

Only six minutes by boat and several hundred years separate the ultra-traditional monks of windswept Papa Stronsay and the outside world.

Far from temptation, removed from the distractions of modern life on their little piece of Orcadian heaven, little has changed in the 20 years since they arrived to convert an old herring gutting shed into Golgotha Monastery, and make the newly acquired 180-acre island of Papa Stronsay – bought for £250,000 – their home.

Soon, however, a little more hustle and bustle could be about to descend on the Transalpine Redemptorists’ stark and deeply traditional way of life.

The monastery is currently in the grip of a mini boom, with rising numbers of people seeking to retreat from the rat race and find heavenly peace with the monks in their "desert in the ocean".

Such is the demand to spend time within the remote monastery’s walls that plans are currently under way to build larger facilities to cope.

For those who make the journey, there will be no luxuries. The deeply traditional monks rise at 3am, eat in silence, even wash dishes to the sound of Latin hymns.

They dress in identical ankle-length black habits, shun possessions and retire to a small, basic cells with just a bed, a desk and a toilet.

Monastic life – apart from their regularly updated blog and occasional YouTube video – has barely changed since the early monks of Papa Stronsay repelled Viking invaders who dared to interrupt their precious way of life.

Work to create new accommodation to meet demand is expected to be carried out by hand by the monks, who have already transformed a former herring gutting shed into a chapel, and who rely on a small private vessel to link them to the nearest island, Stronsay.

With no connection to the National Grid and just a generator to provide power, the monks also have plans to enter the modern age and install wind turbines on the island and to explore other forms of renewable energy.

“We have seen the number of retreat requests increase significantly over the years,” says Fr Magdala Maria, rector at Papa Stronsay, which means "priests’ island of Stronsay".

“There is a plan for a church to be built. There will be larger facilities to cater for a larger number of retreatants.”

In addition to soaring interest from people seeking to spend time in retreat with the monks, the monastery also appears to be a magnet for tourists seeking to explore their remote island.

“There are different types of visitors; they who specifically come to the monastery for some time away, spiritual retreats or peace and quiet. We receive our fair share of visitors as well from the curious, to those who are interested in historic sites, to those who come for religious reasons,” he adds.

“We are always receiving requests for visits even in the windy winter months in Orkney.”

Attractions for visitors to Papa Stronsay include Earl’s Knowle, the longest chambered cairn in the UK, the remains of 11th century St Nicolas’s Chapel, and a rare and perplexing duo of kelp-burning kilns connected by tunnels.

The Transalpine Redemptorists, also known as The Congregation of the Sons of The Most Holy Redeemer, formed in 1988 in order to continue the tradition of celebrating Latin mass. They bought Papa Stronsay 10 years later for around £250,000.

Old herring industry buildings were converted to become a refectory and chapel, and a row of cells were built containing simple furnishings to accommodate up to 40 monks.

Fr. Magdala Maria adds: “We have a steady number of young men joining which is always encouraging to see, so the future seems secure.”

Any rise in visitors and interest in Papa Stronsay is likely to be welcomed by the 350 islanders of Stronsay, just six minutes away by boat, where efforts have been under way for the past two years to lure more tourists.

The seven-mile-long island, known as "Orkney’s Island of Bays", currently attracts around 600 tourists a year to its rugged coastline, dramatic seascapes, sheltered beaches and history – flint arrowheads believed to be 12,000 years old have been found on the island.

However, reaching Stronsay can be challenging: the five-times-a-week flight from Kirkwall to Stronsay takes just eight minutes, but spaces are limited; the ferry may be cheaper but it’s an hour and a half just to get there.

Reaching the monastery at Papa Stronsay means calling ahead and arranging for a boat.

“Stronsay has put in quite an effort to lift its profile both as a holiday destination and somewhere to live and work. As well as housing and better ferry services, we need employment,” says Stronsay-born and bred North Isles councillor Graham Sinclair.

“What holds tourism back is the lack of Scottish Government funding for a better ferry service. It’s woefully poor compared to the Western Isles.”

Fresh hope has come from a controversial source: in October, go-ahead was given by Orkney Islands Council for two new fish farms – the first in the Stronsay area.

Located in two of the island’s three large sandy bays, they will occupy picturesque spots where grey seals, harbour seals, otters and other wildlife currently thrive undisturbed.

The Mill Bay and Bay of Holland fish farms will each comprise 16 circular cages, each 100 metres in circumference and both serviced by their own 300-tonne feed barge.

Cooke Aquaculture’s new farms will create up to nine jobs – however, some have questioned the impact on seals, fish stocks, crab and lobster, as well as expressing fears about the potential visual scar on the unspoiled landscape.

However, Cllr Sinclair says the farms are largely welcomed: “There’s a buzz on the island just now. The fish farms are in development stage, and that’s brought a buzz over the prospect of new jobs in a small community.”

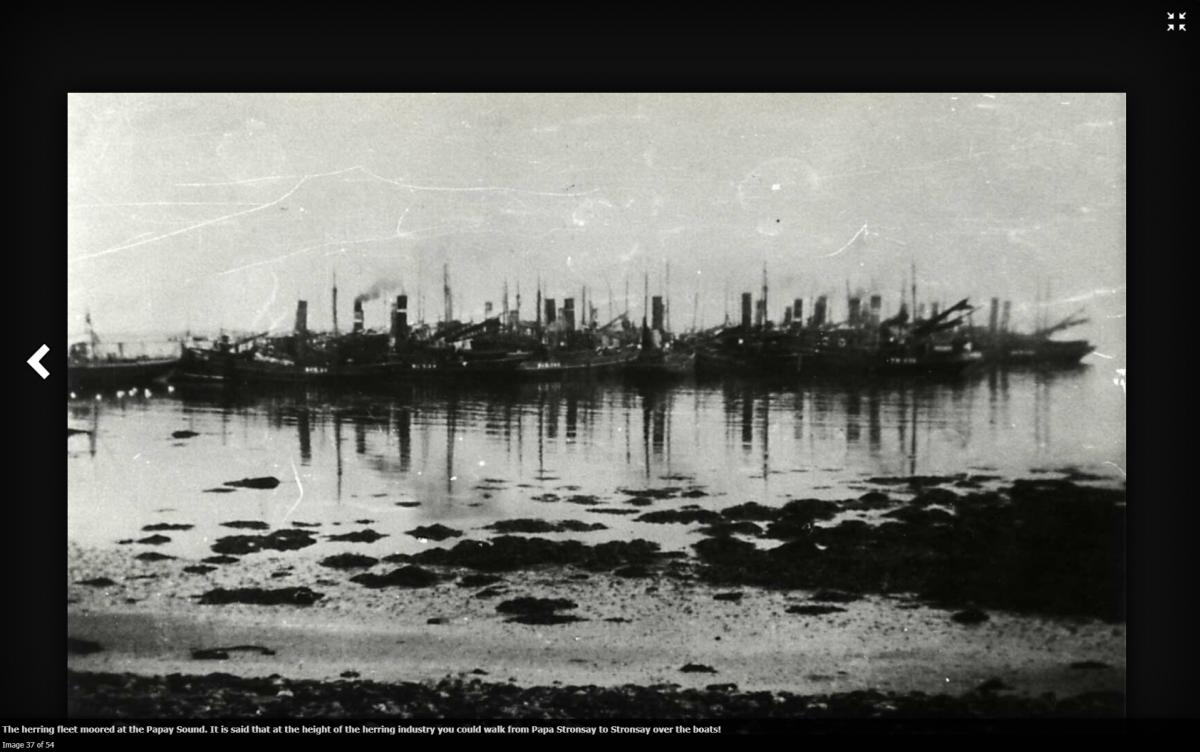

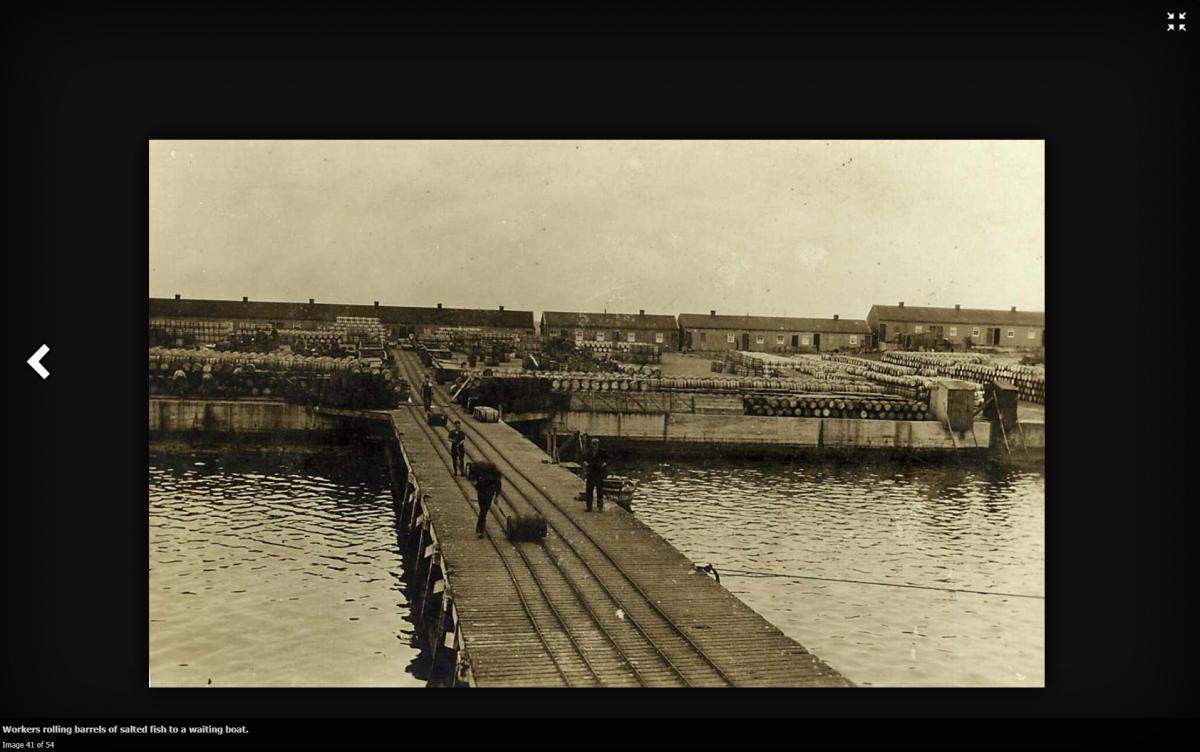

Fish have always played a role in the islands’ industry: Papa Stronsay was once a centre for the herring industry, and at its height in the 1920s, up to 1000 people lived and worked there.

At peak times, so many herring boats packed into the Sound of Papa that it was possible to walk across the boats from Stronsay to Papa Stronsay without touching the water.

The fishing industry collapsed after the Second World War and native islanders left. Today, around 70% of Stronsay’s population is said to be made up of non-native Orcadians.

According to Fr. Magdala Maria, a rise in visitors to the two islands would not adversely affect their peaceful solitude.

“We are not concerned about an increase of tourism, in fact we welcome it,” he says.

“One can say that we have contributed to the influx of visitors to the island of Stronsay over the years. Many of our family members and friends have visited from all over the world, being an international community of monks.

“We always encourage visitors to our island.

“At the same time we want to keep our treasure, Papa Stronsay, a place of joyful silence and solitude, where people can come here to enjoy peace, tranquility and experience the presence of God.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here