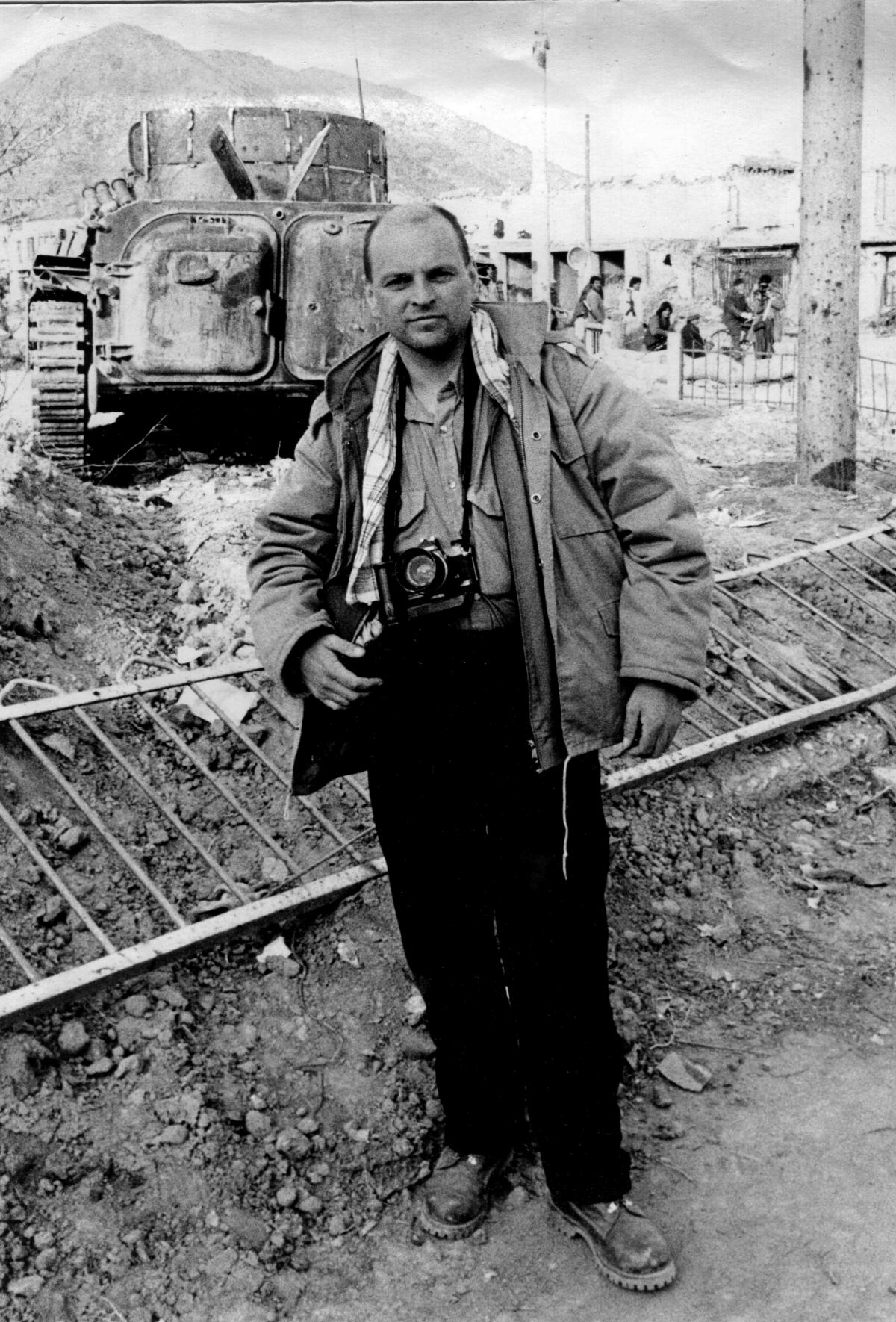

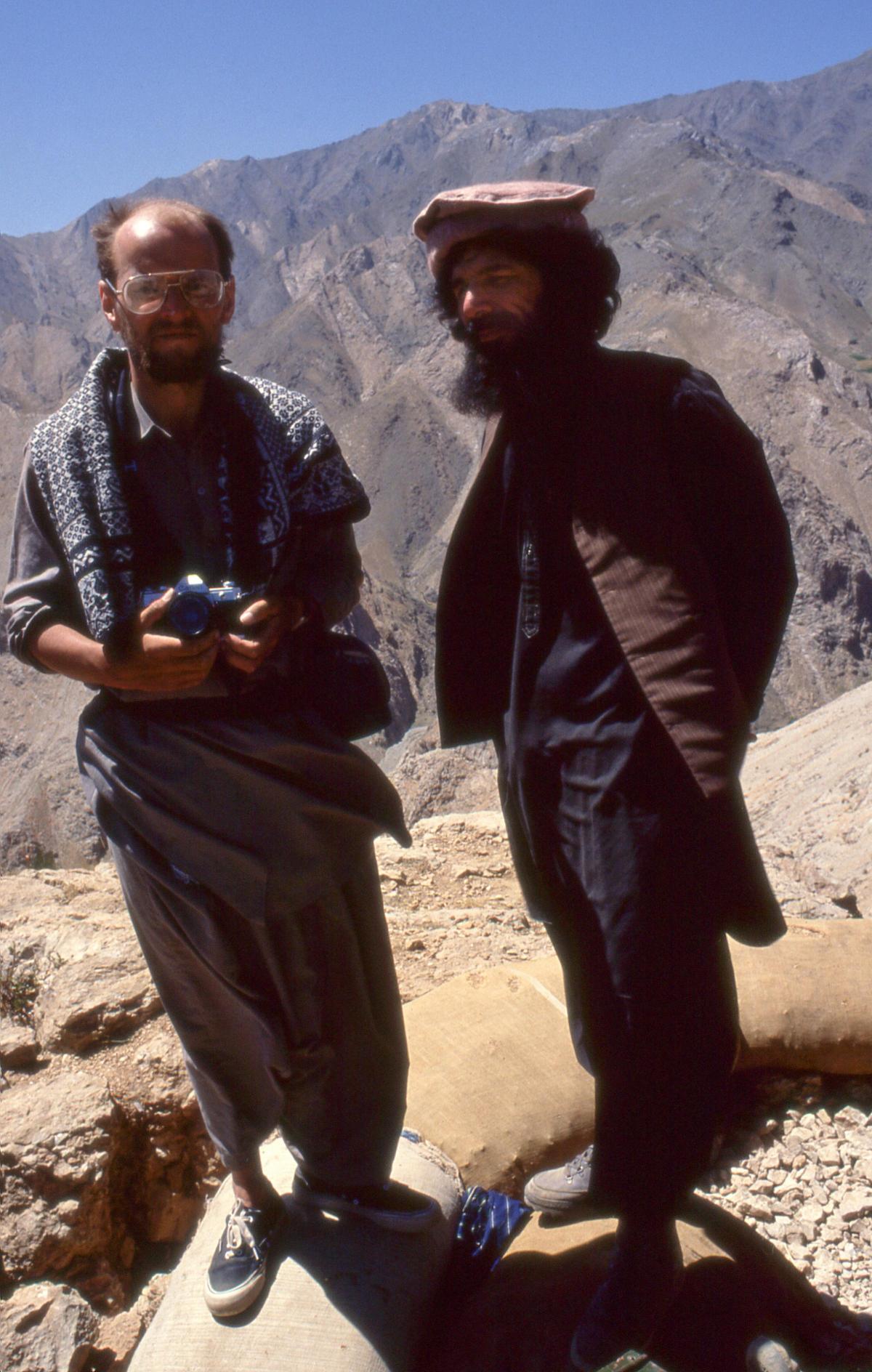

THERE’S a moment in Pictures From Afghanistan, a BBC documentary about The Herald’s acclaimed war reporter, David Pratt, where he meets up with the son of the mujahideen commander, Sayed Anwari, with whom he had formed a strong bond in the 1980s. Anwari is now dead, from cancer, but he dines with his son and some veteran mujahideen. The footage speaks volumes about the passage of time in a country where, throughout all the time Pratt has been visiting, there has been no peace.

Pratt observes: “It’s 40 years that country has been at war. There are kids that I was with in the early 1980s who if they’re still alive will not have known one day of peace. Anwari’s son is 40-ish and he’s never known it. It was the 40th anniversary of the Soviet invasion on Christmas day.”

Readers of this paper, The Herald on Sunday, The Herald and the former Sunday Herald will be familiar with Pratt’s extraordinary photojournalism and reports from war-torn parts of the world – Iraq, Gaza, Syria, Somalia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Bosnia.

The title of a recent exhibition of his photographs, Only With The Heart, was taken from a quote by Antoine de Saint-Exupery: “It is only with the heart that one can see rightly, what is essential is invisible to the eye.”

There are few journalists with more heart, or more commitment to the stories they report on. The focus of this first documentary about his work is Afghanistan because it’s a country he has been visiting for over four decades. It’s where a piece of his heart is.

The idea, he tells says, of reporting from Afghanistan first entered his imagination when he was lying in a bed in a hospital in Nicaragua, feverish with malaria, after he had gone out there, just out of art school, to cover the revolution.

As he suffered in the stifling heat, he came across a copy of National Geographic with Steve McCurry’s iconic image of a young Afghan woman on the cover.

“I flicked through and I remember the pictures were of snowy mountains in Afghanistan – and I was sweltering in this hospital from malaria and, God, it looked so inviting almost by contrast,” he recalls.

Pratt wasn’t a stereotypical war reporter from a privileged background. He was a working-class boy who had grown up in the Hillhouse scheme near Hamilton, which, he says, they used to call “Beirut or Hellhouse”. The first time he was ever shot at, he describes, was in the street there, when he was seven years old and someone “took a pot shot at the postman who had failed to deliver his giro benefit cheque”, and he happened to be walking nearby.

His background is one of the things that makes his early trips all the more remarkable. “Working-class people were not meant to do what I was doing,” he says. “Every foreign correspondent at that time was middle or upper class. There were times when I didn’t have the price of a tube fare to come in from my flat in the southside of Glasgow for meetings in the city centre, but I was planning to go to Afghanistan in a few weeks’ time.

“You would beg, borrow and steal to get the money to get to these places. I felt if I ended up getting clobbered in Afghanistan at least they’re not going to come looking for my overdraft. There was a degree of fate about it.”

Pratt was looking out at the world at a particular political moment – the early 1980s, following the revolution in Nicaragua, the Iranian revolution, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, all of which had taken place in 1979. “Afghanistan wasn’t really known at that time,” he recalls. “It was still an obscure backwater. The only thing you’d read about it was the hippy trail. But the politics of the region weren’t known.

“The religious aspect of it was misunderstood. A lot of the mujahideen groups were Islamist, but they weren’t absolutely rabid fundamentalists like the Taliban. They just didn’t like the bloody Russians. And can you blame them?”

Pratt didn’t head out there looking for a specific story – though he had an interest in guerrilla movements and underdogs. “I wasn’t looking at the grand politics of things,” he says. “I was very interested in how people lived. Although the irony is that by the stage I went to Afghanistan, I was very left-wing. I was actually a card-carrying member of the communist party.

“If the mujahideen had known I was a communist it would have been curtains. They wouldn’t have waited to find out that I was interested in the notion of resistance and guerrilla movements.”

His route into Afghanistan involved illegally crossing the border from Pakistan. The way Pratt tells it, it sounds like after a small amount of research. He flew to Peshawar on a wing and a prayer – with few connections. “Afghanaid was my first port of call in Peshawar and they kind of sent me in the direction of one or two mujahideen, but I had to make those approaches myself.”

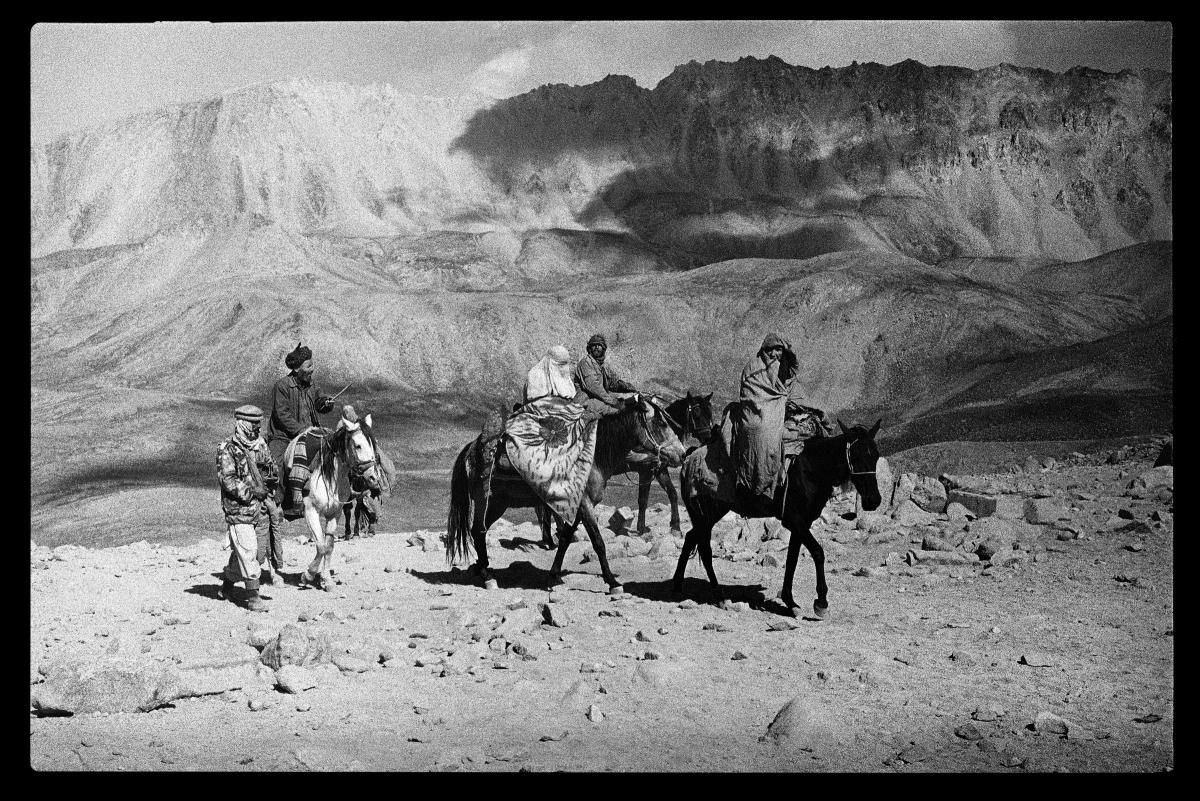

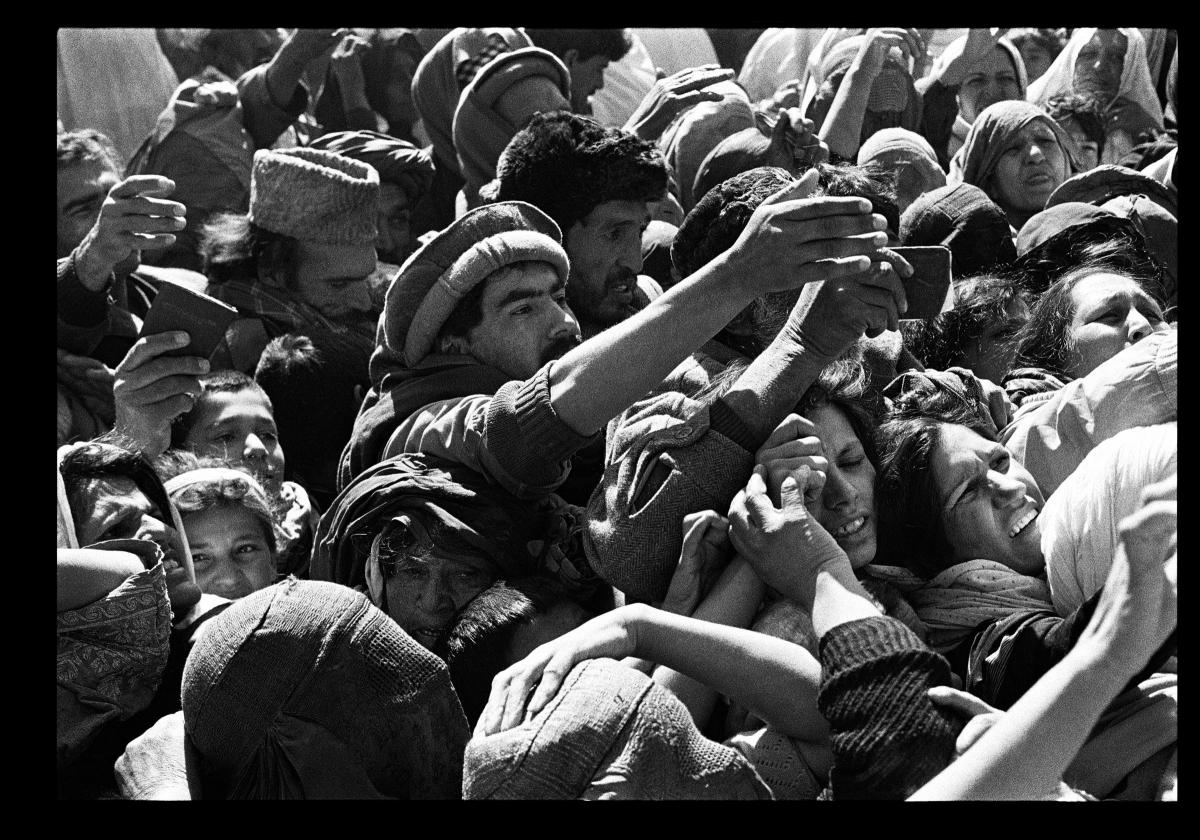

What strikes you almost immediately is how risky his forays into Afghanistan were. He travelled with small groups of mujahideen, slept in caves, moved at night, and, when he fell ill, which he did, would have to be smuggled back out of the country. Often the groups he was with were making 14-hour marches through the Hindu Kush.

He was also highly dependent on the mujahideen guerrillas who took him into the country, people like Sayed Anwari, with whom he formed a close friendship. “Without them, it would have been impossible. I went back and forward across the border in all these different guises. I got caught dressed as a woman in a burka. I went in a coffin, behind grain sacks. Anwari would organise these elaborate ways of getting in and out. I was completely dependent on them.”

His life was at risk on countless occasions. In the film, he describes one occasion when he and the group he was with had to beat a retreat from mortar bombardment. “Rounds were landing all around you – people were going into the air, pieces of them coming off, body parts everywhere.”

As he and the others around him ran, he passed a man whose knee had been blown off. The man put his hand out as if to ask for help, but shells were still landing all around him and he had to run on. “There is a kind of guilt about that,” Pratt says in the film.

You can’t help but wonder what his parents and friends must have been thinking. In those times, if you travelled in remote areas, you were essentially dropping off the map, cutting all connection with home. “There were no mobile phones,” he says. “There was no contact. Some of the trips were months on end, and you would cross the border illegally into Afghanistan and disappear off the radar. I might never have come back.”

His parents however, were already used to these disappearances. At 13 years old, already a keen mountaineer, he was hitchhiking to Glencoe, sleeping under bridges and tackling serious rock-climbing routes. “I was already doing that, so the idea of prolonged absences was no shock to my parents,” he says.

The assumption when he was growing up had always been that he would join the military. “It was a very male-dominated family,” says Pratt. “My uncles were in the military. My father had done his national service in the Middle East.” That upbringing instilled in him “an urge to see the world”. He goes on: “The military may have been a way of doing that, but in the end I got really politically opposed to things military.”

Instead he did “the polar opposite” and went to Glasgow School of Art, and that was where his journey towards documentary photography began. “Some of my close student friends could see my increasing interest in documentary work. They were seeing a drift towards the political and the fact that a painting was too contemplative for me. The camera was a more immediate tool.”

Pratt made scores of trips into Afghanistan during the 1980s. Some were for only two or three days, but his longest was for over three months.

What does he think he learned in those early years?

“It was mostly finding out about myself,” he says. “It was physically and psychologically very hard. I was on my own. You would be three months in the mountains. My interpreter was a young engineering student from Kabul University who did not want to be a guerilla and didn’t want to be hoofing over the Hindu Kush mountains, so when he was given the task by Anwari he actually loathed me because I’d got him into this situation. We became great friends. So those long hikes over the mountains were finding out about ourselves.”

Pratt kept going back to Afghanistan even after the Soviet withdrawal in 1988. “From the 1990s, the mujahideen were bickering among themselves,” he recalls. “It was horrendous and the West was not really interested. I was determined to cover it simply because it wasn’t getting covered. No-one was interested now it was Afghans fighting Afghans, not Afghans fighting the Communists any more.”

Afghanistan remains war-torn, a precarious and unstable democracy. What happens there is little talked about in the West – a recent New York Times editorial described it as “The Unspeakable War”. Meanwhile, the Taliban wages violence and controls many parts of the country.

In the documentary, Pratt talks with a Taliban leader by telephone, and is told that peace will only be possible in Afghanistan if the barriers to it are lifted – and that this would “require all foreign troops to leave Afghanistan”. In recent days that possibility has come closer with the announcement from the Taliban that they are on the threshold of a historic agreement with the USA which would involve withdrawal of troops.

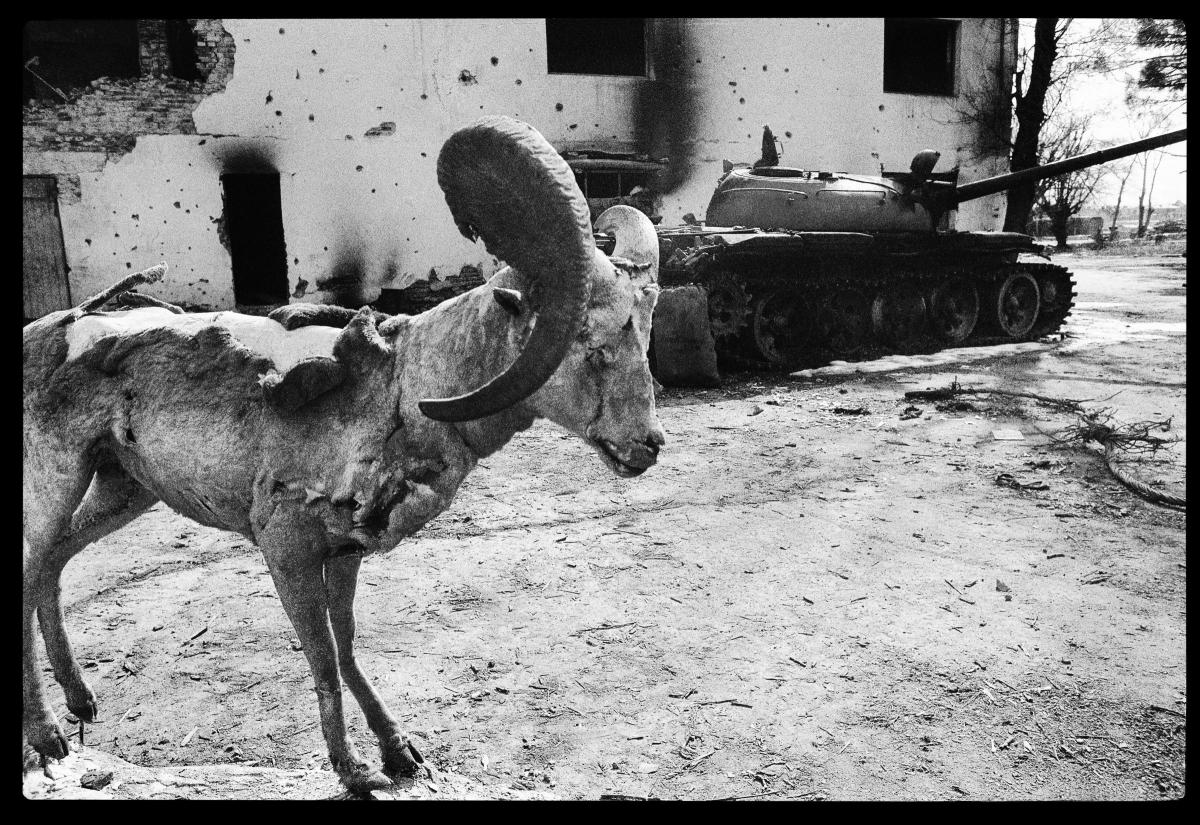

During his film, Pratt returns to many of the frontlines from which he reported. The zoo, the site of his startling 1995 image of a sheep wandering across a background of rubble and armoured tank, now feels like a bustling attraction in any city. But, he says, Kabul remains a scary place. When his documentary team visited the Puli Mahmood Kahn district, another former frontline, they were told by their security officers that people up the street were making calls on their mobile phones.

“That area is Taliban central. We bundled into the car and shot off. We had to get up the street and we did a right on to the main highway and the security guy told the driver to do a complete U-turn in the middle of the street and then go back the other way because otherwise the Taliban could ambush us further on. You’re living with that all the time in Kabul.”

Pratt went on to cover conflicts in many other parts of the world. The longer he went out for, he says, the harder it would be to adjust. “After I was kidnapped in Bosnia, I went to ground for about six months.”

He also found it hard sometimes to be sympathetic when people back home were stuck on petty concerns.

“I remember coming back from Nicaragua,” says Pratt. “I was really quite sick and there was a woman on the last leg from Madrid to London and all she went on about was whether the driver she had would be waiting for her at Heathrow airport. Three days earlier I’d been in a refugee camp and I’d watched them put a machine gun in an adjacent area and fire on the refugees in the camp. It’s difficult not to get angry. But people’s problems are relative.”

For Pratt, the process of making the documentary has been “cathartic”. The story it tells is of world events, but also his own life. Part of it happens back home, in Glasgow, with his partner, Caron, who has stuck with him through his repeated disappearances – a fact he says is “amazing”. Recently, he says, he overheard Caron talking about how miserable he was because he was waiting for a visa to go out to Iraq. If he’s not there when something is happening, she observes, he’s always miserable.

“I remember talking to Marie Colvin about that,” he says. “Marie was the worst if something was happening elsewhere. Even when she was on a job she was thinking of the next job. And if it’s a part of the world you’re really familiar with – Afghanistan or Israel-Palestine – it’s twice as bad.”

Did he ever think about doing anything else? “Not really. Once I got into it that was it. The experience of arriving in Nicaragua at dawn, swaying palm trees, and humidity and crickets. Straight out of Graham Greene. Wonderful. You can’t go back from that, really.”

The Glasgow Film Festival premiere screening of Pictures From Afghanistan followed by a Q&A with David Pratt, chaired by Allan Little, is at the Glasgow Film Theatre on Sunday, March 1, at 1.15pm. Tickets available on the GFF website

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here