By Maggie Ritchie

JIMMY Reid was haunted by memories of desperate poverty all his life. His early childhood in the Glasgow Gorbals slums, where three of his sisters died in infancy, drove him to fight to improve the lot of working-class people.

Born into severe poverty in 1932, Reid was drawn to radical politics as a way to bring about social reform, his heroic efforts for social change earning him the title “the best MP Scotland never had”.

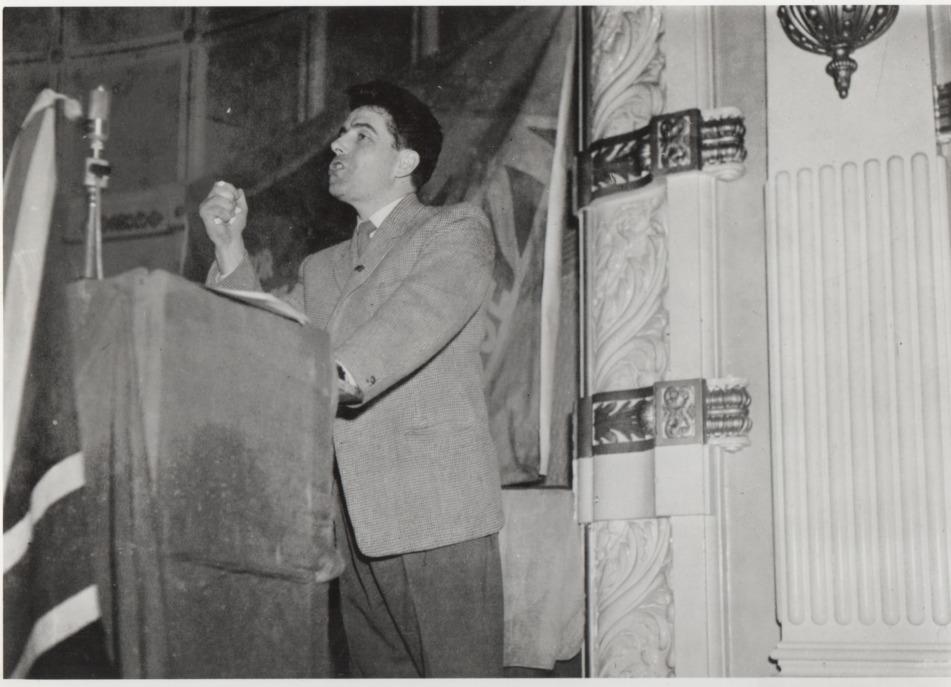

His passion and charisma, allied to a fearless ability for public speaking, made people from all walks of life sit up and listen – even if they didn’t necessarily agree with him.

Now a new biography traces Reid’s remarkable life from a poverty-stricken background in Glasgow to being thrown into the national limelight as the spokesman for the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders’ work-in.

The authors of Jimmy Reid: A Clyde-built Man, who will be appearing at the Aye Write! festival next month, interviewed family members, friends and comrades, as well as delving into the University of Glasgow archives to shed new light on how Reid became a symbol of working-class defiance.

“We were bowled over by the audacity of the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders shop stewards and by Reid’s role as leader and political icon in his own right, and he was arguably one of the greatest political orators since 1945,” said Dr William Knox, honorary senior lecturer in Scottish history at the University of St Andrews.

His co-author, Professor Alan McKinlay, professor of human resource management at Newcastle University Business School, said: “I was a schoolboy when the UCS work-in happened between 1971 and 1972, and we were one of the schools that collected money for the shipyard workers.

“My dad worked at Rolls-Royce and, like the UCS men, had faced redundancy, and I admired these audacious men who stood up to market forces.”

Researching the book uncovered some startling revelations about the man who, along with fellow shop stewards Jimmy Airlie, Sammy Gilmore and Sammy Barr, led and won a major industrial struggle.

For McKinlay, one of the most striking aspects of Reid’s life that emerged from the research was how intensely personal his politics were.

“The image that stayed in my mind was of Jimmy as a young boy watching his father cradle his dying sister in his arms just as midnight struck on Hogmanay and Auld Lang Syne rang out in the streets outside,” he said.

To Reid, his three infant sisters “had been murdered – whatever it said in the death certificate, they should have put down ‘social conditions’ as the cause”.

“His visceral personal politics came down to this bedrock of morality,” said McKinlay.

“It was the devastating impact of poverty and the desire to eradicate it that shaped his politics from an early age,” he added. “Even in his last years he never ceased to be emotional when the bells rang out to announce the arrival of the New Year.”

When the family moved to Govan, their circumstances improved and Reid did well at St Gerard’s Senior Secondary, where he was streamed for university and read widely. Once asked by Jonathan Miller, the theatre director, at which university he’d been educated Reid told him: “Govan public library.”

Despite his obvious intelligence, Reid left school at 14 as his “expectations never involved higher education. I did not know anybody who went to university from the streets of Govan”, he would say.

Knox was struck by Reid’s contradictory nature – a product of the macho culture of the shipyards who loved cricket and played the saxophone.

“I was surprised to learn that Reid started his working life in a stockbroker’s office, where his employer recognised his ability,” said Knox.

The young communist firebrand struck up a rapport with the senior partner who promised him a bright career as a future partner if he stayed on, but Reid’s socialist convictions were incompatible with working in a stockbroking firm.

However, this early training proved invaluable as it gave him an understanding of the workings of finance capital. He said: “I’ve always been able to read the stock exchange, and in debates with people it has become quite useful.”

Reid signed up as an engineering apprentice in the Govan shipyards, but the Scottish shipping industry was already in decline. There were 28 shipyards on the Clyde in 1950 but by 1968 only nine remained.

In 1971, the Heath government attempted to close Upper Clyde Shipbuilders, which had been merged from five yards.

Refused further state support, UCS was forced into liquidation despite the yards having a full order book and a forecasted profit for 1972. The shop stewards, including Reid, came up with the idea of a work-in rather than a strike, which would hand victory to the government.

They would have “cheered us out of the yards”, said Reid. “If we go out on strike, once we’re out on the street, they’ll padlock the gates. We’ll have done their job for them.”

“The University of Glasgow archives gave us access to tape recordings of the shop stewards’ private meetings,” said McKinlay. “They were very conscious that what they were doing was unprecedented, and that they were taking on a huge burden that they couldn’t mess up.

“The humour of these men really came through – that rough, caustic Glasgow humour. People often underestimated Reid because of this sense of humour, and when they heard his accent. But behind all that was an intellect and a breadth of learning.”

Reid’s intelligence and oratorical powers came to the fore during the work-in, and his electrifying address to the workforce became famous: “There’s a basic elementary right invoked here – that’s our right to work. We’re no strikers. We are responsible people and we will conduct ourselves with dignity and discipline. There will be no hooliganism. There will be no vandalism. There will be no bevvying, because the world is watching us.”

The subsequent government climbdown was viewed as a tremendous victory, but the responsibility for saving the livelihoods of thousands of families took its toll on Reid, who was twice admitted to hospital. His daughter Eileen told the authors he was “public property ... we hardly ever saw him ... our whole lives were taken over ... no normal stuff like going to the swimming baths”.

His widow Joan said: “He always whistled coming up the stairs. And if he wasn’t whistling then you knew something was wrong. He never whistled during the work-in.”

Despite being a household name after helping to save around 8,000 jobs, Reid was rejected when he stood as an MP for Central Dunbartonshire. He left the Communist Party but was also defeated in Dundee East as a Labour candidate in 1979 by the SNP and began a career as a columnist and broadcaster. Disillusioned by New Labour, he resigned from the party in 1998 and joined the SNP in 2005.

When Reid died in 2010, Govan shipyard workers lined the road as his cortege went past. At his funeral, former Prime Minister Gordon Brown said: “The fact there is still a shipbuilding industry in Scotland today is in large measure because of the inspirational campaigns that he waged.”

McKinlay said: “If his life had a message it was that morality rather than economics should be the bedrock of policymaking.”

•William Knox and Alan McKinlay will discuss Jimmy Reid: A Clyde-built Man at Aye Write! on Sunday, March 22 at 8pm.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel