TODAY, Germany joins a growing list of countries where vaccination is compulsory. After a spike in measles cases in recent years, Berlin has passed a law which requires all pre-schoolers, school children, and adults who work in schools and hospitals to be immunised against the disease.

Vaccination rates are falling in the West, and immunisation for measles is now mandatory in 12 European countries, including France and Italy.

Measles is on the rise in Britain too. So should we follow suit? Should compulsory vaccination be the norm? The UK Health Secretary, Matt Hancock, has already said that he’s “looking very seriously” at compulsory vaccination for school children.

Figures show that childhood immunisation rates are dropping across Scotland, and the rest of the UK.

The question about whether Britain should follow Germany’s lead is timely – as the rapid spread of coronavirus underlines just how vulnerable society is to mass outbreaks in the era of globalisation.

A coronavirus vaccine is still some way off, but if one was developed tomorrow, there would be queues outside clinics across the country.

Yet, at the same time, the so-called anti-vax movement is on the rise, as growing numbers of parents turn their back on the idea of immunising their children for fear of causing some greater harm, or because of religious beliefs.

Many anti-vaxxers are convinced that they risk “giving” their child autism if they have them vaccinated. That belief, however, is scientific nonsense.

Why Germany?

The decision was made in the midst of a global rise in measles cases. From today, if a parent refuses to get their child immunised in Germany, they’ll face a fine of around £2,000 and their child will be banned from nursery or school.

The German law was passed after the nation listened to months of parliamentary debate, including testimony from medics who spoke both for and against compulsory vaccination.

Germany’s health minister described the move as both “child protection” and a bid to ensure that all members of society were protected. The World Health Organisation says 95% of any given population must be vaccinated to prevent mass outbreaks. It’s called “herd immunity”.

Measles is surging in Europe. In 2016, there were 5,273 cases. By 2018, that had risen to 84,462. In the first six months of 2019, there were nearly 90,000 cases and 37 deaths. In the same period, there were 489 cases of measles in the UK – many linked to European travel.

The moral dilemma

At the heart of the issue of compulsory vaccination lie two huge moral questions. First, should any parent have the right to refuse vaccination and endanger the life of their child?

Second, does any parent have the right to put the rest of society at risk by refusing vaccination for their child?

If the answer to those questions is no, then the path starts to open up towards a policy of compulsory vaccination.

The main parties in Germany – the Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats – supported compulsory vaccination legislation. However, the Green Party offered an alternative.

Greens were very critical of compulsion as a public health policy, and suggested instead a major education campaign. However, any attempt to raise “public awareness” about the necessity of vaccination is an uphill struggle in the age of online conspiracy theories, which is where most anti-vax propaganda springs from.

The return of measles

Last summer, WHO announced that measles had officially returned to four European nations previously deemed free of the disease – Britain, Albania, Greece, and the Czech Republic.

The WHO announcement was made in the lead-up to Germany voting for compulsory vaccination. The loss of the UK’s measles-free status is surely a warning sign that something is going wrong when it comes to vaccination.

Prior to widespread measles vaccination being introduced in the early 1960s, the disease killed around 2.6 million people globally every year. By 2017, measles was killing only 110,000 a year around the planet.

Across the Western world measles is making a comeback. Even though the United States officially “eliminated” measles in 2000, there were outbreaks across the country last year. Portland, Oregon, saw officials declare a public health emergency after one outbreak.

In 2018, there were 349 cases of measles in 26 states. The Centre for Disease Control (CDC) confirmed this was “the second-greatest number of annual cases reported since measles was eliminated”.

Most had not been vaccinated against measles. The CDC says US outbreaks are down to travellers bringing measles back from overseas, and the virus then finding a breeding ground among the unvaccinated.

In some parts of America, such as Washington state, only 76% of children were fully vaccinated in 2016 – although in other areas the rate is as low as 70%.

In Washington, only 1% of children were exempt from vaccination on medical grounds – the rest refused vaccination because of their parents’ religious or philosophical beliefs.

WHO has described the anti-vax movement as among the 10 biggest global health threats. “Measles, for example, has seen a 30% increase in cases globally,” WHO said.

“The reasons for this rise are complex, and not all of these cases are due to vaccine hesitancy.

“However, some countries that were close to eliminating the disease have seen a resurgence.”

Global dimension

In January 2019, health officials blamed distrust of vaccine for an outbreak of measles among New York’s Orthodox Jewish community. Some 58 people were infected after a child caught the disease.

“The initial child with measles was unvaccinated and acquired measles on a visit to Israel, where a large outbreak of the disease is occurring,” the New York City health department said.

“Since then, there have been additional children from Brooklyn who were unvaccinated and acquired measles while in Israel.”

Measles is still relatively common in Africa and Asia. Some 81 people brought measles back to America from other countries in 2018.

A study in the medical journal BMC Medicine, in May 2019, into measles-immunisation policies in seven different healthcare systems, found that “recent policies aimed at increasing childhood immunisation rates through the introduction of compulsory vaccination are certainly producing positive effects, by raising the proportion of children protected against measles”.

Publications by the British Medical Association have referred to the anti-vaccination movement as a “needless waste of life”.

Some 7% of the world’s population thinks vaccines are dangerous. But in some Western countries – where online conspiracy theories proliferate most – opposition to vaccines is much higher.

In France, one in three disagree when asked if vaccines are safe. France has seen a 462% rise in the number of measles cases, from 518 in 2017 to 2913 in 2018.

Of the 301 people diagnosed with measles between April and June last year in England, 266 were aged 15 or over and had not been vaccinated.

The 301 cases of measles represented a substantial increase in the rate of infection in just three months compared with January-April of the same year.

Nearly half of those who contracted mumps in Britain were unvaccinated. Last year, between April and June, some 2,028 people were infected by mumps. The previous quarter saw just 795 people contract the illness. The 2,028 figure represents a 12-fold increase on the 170 diagnoses of mumps in the last three months of 2018.

“These stark rises in mumps and measles cases show that complacency about vaccines is misplaced and dangerous,” said Simon Stevens, the chief executive of NHS England. He has promised to “tackle the fake news peddled on social media”.

Lies, damned lies

Much of the anti-vax panic goes back to the discredited claims of medical doctor Andrew Wakefield. He claimed in The Lancet in 1998 that the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccine was linked to autism. The General Medical Council later found that Wakefield had been dishonest in his research. The Lancet retracted the article. Wakefield was later struck off.

The British Medical Journal described Wakefield’s claims as “an elaborate fraud”. Wakefield was accused in reports of intending to financially profit from his bogus research. The scandal did little to silence Wakefield. He directed the documentary Vaxxed: From Cover-Up To Catastrophe in 2016.

Ian Lipkin, professor of epidemiology and director of the Centre for Infection and Immunity at Columbia University, compared the film to “science fiction”, adding: “As a documentary it misrepresents what science knows about autism, undermines public confidence in the safety and efficacy of vaccines, and attacks the integrity of legitimate scientists and public health officials.”

The scientific evidence in favour of vaccination is insurmountable. Vaccines eradicated smallpox, which once killed one in seven children in Europe. Vaccines have also nearly wiped out polio. Estimates have been made that if every child in the United States was given full vaccinations from birth to adolescence some 33,000 lives would be saved and 14 million infections prevented.

However, Facebook’s use of micro-targeting algorithms allows anti-vaccine groups to aim adverts at the parents of young children, and undermine science. One fairly typical ad read: “Healthy 14-week-old infant gets 8 vaccines and dies within 24 [hours].”

What history tells us

We just need to look back into the past to see how dangerous the anti-vax movement is – take Stockholm in 1873. Religious objections led to an anti-vaccination campaign. This resulted in a drop in the take-up of vaccination in Stockholm to just over 40%, compared to around 90% in the rest of Sweden.

A major smallpox epidemic broke out. That led to a rise in vaccine uptake, and the epidemic came to an end.

In the UK in the 1970s, questions were raised about the risks and effectiveness of the whooping cough vaccine. Vaccination dropped from 81% to 31%. The result was whooping cough epidemics and a number of deaths of children. Vaccine uptake then increased to above 90% and the disease declined dramatically.

After the MMR controversy, there was a measles outbreak in Ireland. Immunisation levels had fallen to below 80% nationally. In some parts of Dublin the uptake was as low as 60%. There were more than 300 cases and three children died.

In Wales in 2013, there was an outbreak of measles in Swansea. Some 1,219 were infected, one died. In 1995, the uptake of MMR in Wales was 94%. In Swansea by 2003, however, in the wake of the MMR panic, uptake was as low as 67.5%.

What’s to be done

Australia tackled the anti-vax movement by introducing “no jab, no pay” and “no jab, no play”. This withholds state payments like child care benefit, child care rebate and family Tax benefit for parents who have children not fully immunised. It also penalises childcare centres which admit non-vaccinated children.

“No jab, no pay” was introduced in 2015. By July 2016, 148,000 children who had not been previously fully immunised were vaccinated.

Many people understandably feel uncomfortable with this level of parental coercion. The British Society for Immunology’s chief executive, Dr Doug Brown, favours public information campaigns.

“To make this compulsory in the UK, there are concerns that it could increase current health inequalities and alienate parents with questions on vaccination,” he said.

“There are also major doubts about how such a policy could be implemented and monitored and risks resulting in unintended consequences as well as a loss of public confidence in vaccines.”

Shirley Cramer, chief executive of the Royal Society for Public Health, says: “Compulsory vaccination should be a last resort.”

The politics

Aside from the politically problematic fact that health is a devolved matter, there’s one issue which complicates the idea of compulsory vaccination across the UK – regional disparity.

In Scotland and Northern Ireland the take-up rate for MMR is 95%. Although that figure is high for Scotland, overall vaccination rates are still dropping here. In northeast England the take-up rate is 94.5%, but in London it is just 83%.

On such a small group of islands, compulsory vaccination would be rendered ineffective without all four UK nations taking part. But why should Scotland and Northern Ireland – which have herd immunity – consider compulsory vaccination when the issue is primarily a problem elsewhere?

Public opinion will be the big test. In the age of coronavirus do we have the tolerance, as a nation, for those of us who would put others, as well as themselves and their own children, at risk when it comes to health?

What we know for sure is that the German experience of compulsory vaccination which begins today will be watched closely by politicians and health professionals around the world.

The rise in measles cases, coming at a when the world is focused on coronavirus, may create a tipping point where the public feels health outweighs parental liberty. We can already see how little opposition there is in the West to health-enforcement measures such as quarantine in the face of coronavirus.

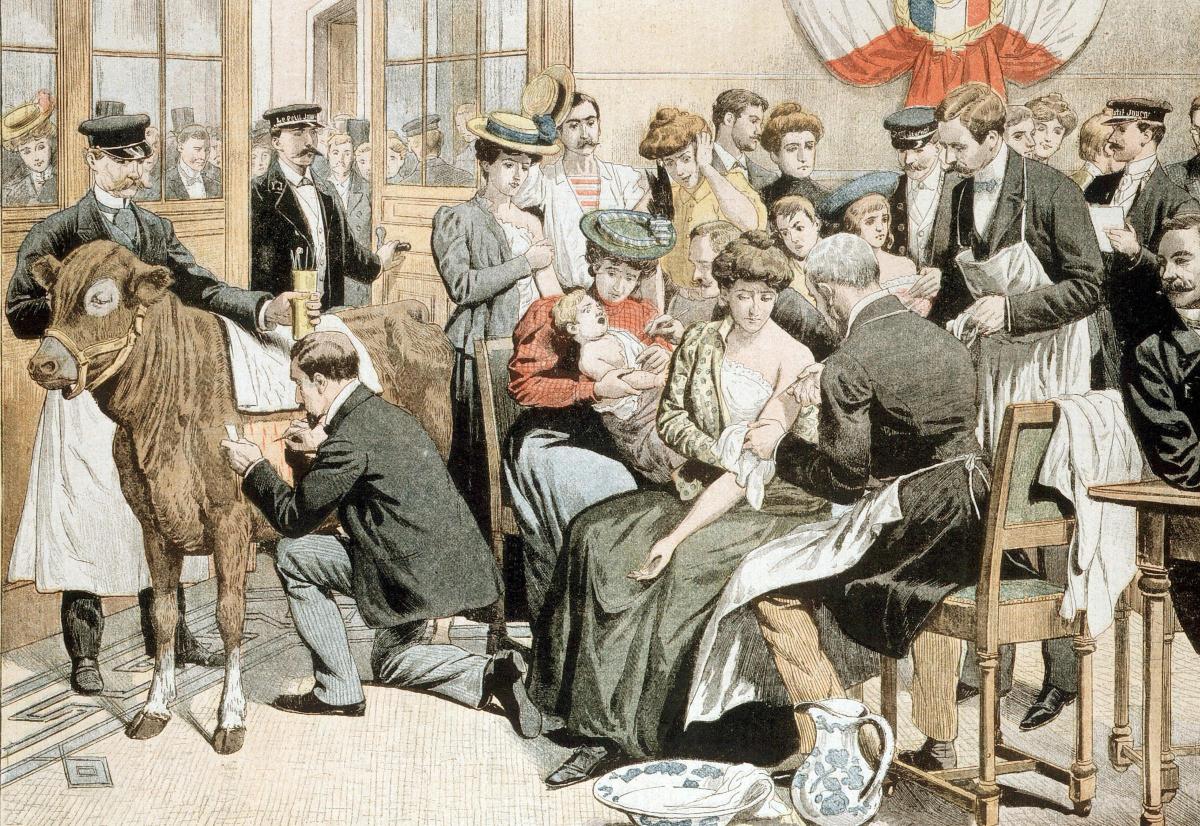

We should also remember that Britain has made vaccination compulsory in the past. In 1853, the Vaccination Act required that all children be vaccinated against smallpox. Refusal resulted in a £1 fine – a lot of money in Victorian times. Mandatory vaccination only came to an end in 1948 ... once smallpox was deemed effectively eradicated in Britain, and public health secure.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel