Layer upon layer of wallpaper is shedding new light on the lives of New Lanark’s residents, reports Sandra Dick

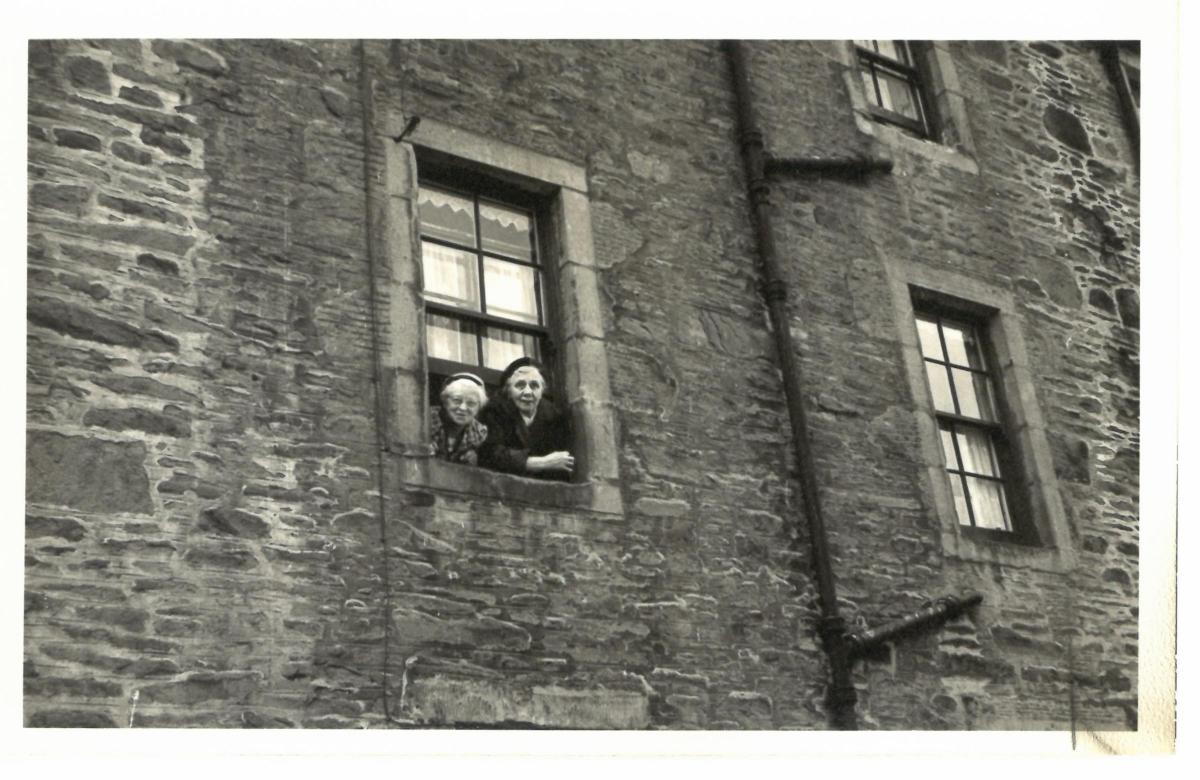

Viewed through grainy black and white pictures and across the decades, life in Scotland’s mill village of New Lanark might seem a little grey.

But new research at one of the village’s tenements for workers has uncovered signs of how the residents revelled in a blaze of colour, with an unexpected pride in decorating their simple homes.

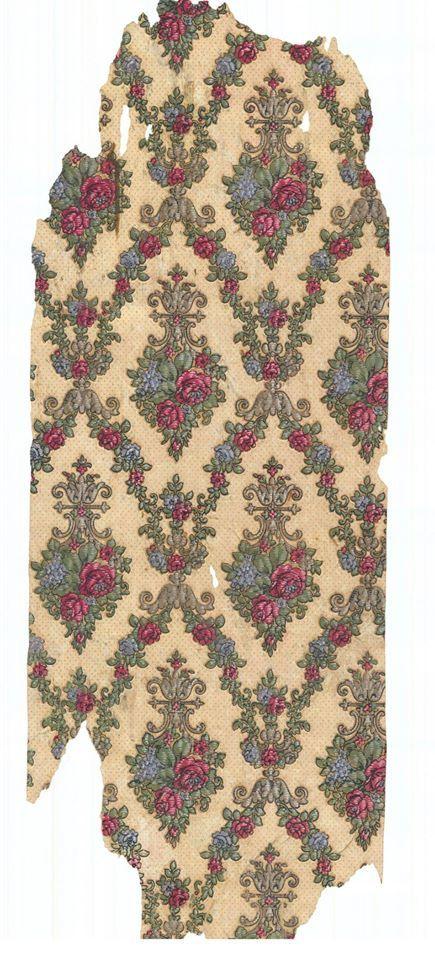

Layer upon layer of fragile but vividly coloured wallpaper with designs and patterns that reflect fashions of the time have been carefully uncovered in tenement homes which, from the outside at least, look uniform, a little dull and far from vibrant.

The discovery suggests families living in at least one particular tenement of the time capsule village took great delight in following interior trends, perhaps even indulging in a degree of “keeping up with the Joneses” as they ensured their tiny homes were at the very cutting edge of fashion.

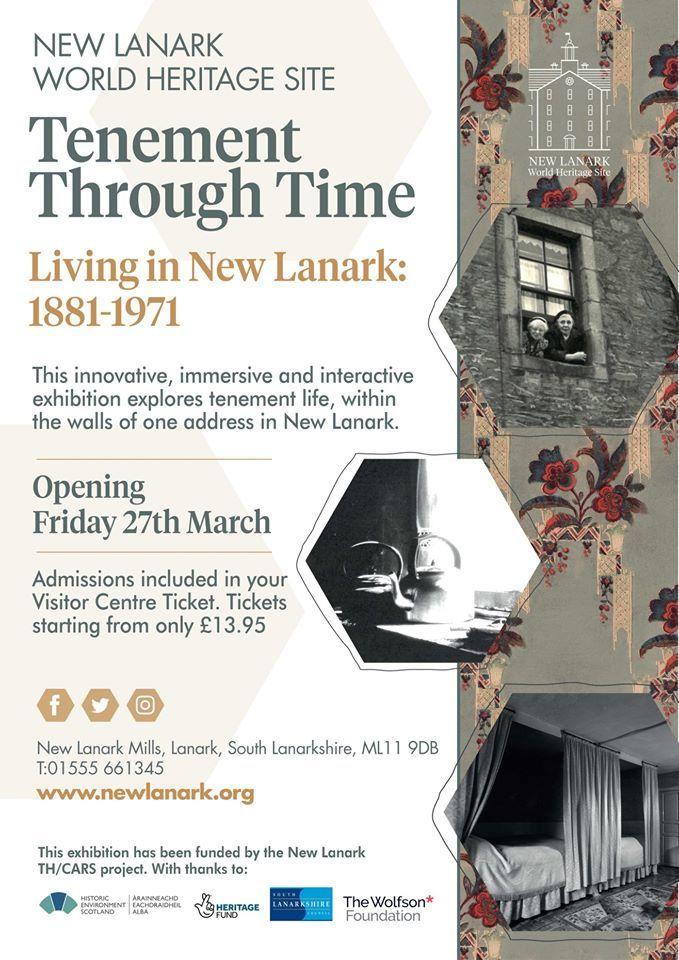

The fascinating insight into how families lived in and loved their humble abodes will be revealed in full in a major new exhibition set to be launched at the World Heritage Site later this year.

Tenement Through Time: Living In New Lanark 1881-1971 will spotlight four of families who lived in one building known as “The Museum Stair”, a beautifully preserved example of early industrial housing but which is so fragile that it is only open to a handful of specialist visitors.

The exhibition will offer the public a chance to see it recreated in an immersive and high-tech permanent presentation spanning 90 years of its residents’ lives, right up to the point the last one packed her bags in the early 1970s and left.

According to Shona Walker, who is project co-ordinator of the New Lanark Townscape Heritage/Conservation Area Regeneration Scheme (TH/CARS) project, research into village life has uncovered an unexpected and very colourful glimpse into the lives of New Lanark families.

“Our research uncovered personal artefacts, photographs and family trees. We found out about the variety of jobs they did and their children’s achievements at school.

“A lot of people will think of working-class houses like these as being very poor and very shabby, all looking the same. But that is not the case.”

Researchers were surprised to uncover more than 180 different wallpaper samples in the one tenement, most of them high-quality papers which have retained their vibrancy despite being papered over multiple times. They range from grand designs reflecting the late Victorian era to Art Nouveau papers, jazzy sixties and early seventies designs.

“Every house has different paper,” adds Walker. “We have got paper from 1880 that would have been very expensive.

“The late 19th-century papers are very heavily ornamented, with large patterns.

“From the twenties and thirties, there are real ‘art deco’ papers, while by the forties and fifties they become very floral and ‘Festival of Britain’ in style. Then by the early sixties, the colours are more mottled and it’s not as big and bold as it was.”

As well as highlighting families changing tastes and enthusiasm for keeping up with interior fashions, the findings shine a light on the way they lived and the choices they were able to make.

It also raises the question of how families could seek out the latest styles of wallpaper, and the influences travel and their employers’ links with far-flung locations may have had on their choices.

“It shows they decorated frequently,” Walker continues. “We can see that they often changed their wallpaper every five or 10 years – which is possibly more than some of us do now. We can see that they took real pride in their houses.”

While decorating seems to have been a regular event, stripping off existing paper and carefully preparing the walls for a new layer – much to the researchers’ delight – was not. “One wall was found to have 22 layers of paper,” adds Walker.

Such is the scale of the find that there are plans to digitise the uncovered paper to create an archive for researchers interested in the history of the New Lanark site, but also designers concerned in long-lost patterns, colour trends and interior fashions.

“There are very few photographs of inside families’ homes so the wallpapers are a very interesting way of finding out more about inside their homes.”

Once the exhibition opens, visitors will be able to stand in a virtual room while the walls shift to show the evolving wallpaper styles.

Wallpaper conservator Allyson McDermott said: “Within the building there is a remarkable survival of a wealth of original materials and artefacts such as paint, wallpaper, linoleum and fireplaces offering an extraordinary insight into the decorative history of the ‘ordinary’ domestic interior.”

Work on the exhibition has been funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund and Historic Environment Scotland through the New Lanark

TH/CARS project. It also explores the lesser-known history of The Gourock Ropework Company, the last company to operate at the site.

The New Lanark cotton mills were founded in 1786. By the early 19th century they were in the hands of a partnership that included Robert Owen, an influential social reformer. In Owen’s time, some 2,500 people lived at New Lanark, many from the poorhouses of Glasgow and Edinburgh. They benefited from services and schools.

By the early 1900s, New Lanark was owned by the Lanark Spinning Company, which went on to merge with The Gourock Ropework Company which remained in control until the mills closed in 1968.

In the early 9th century, an entire family would have lived one room. However, living conditions gradually improved and in the early 20th century the village’s proprietors provided free electricity.

By 1933, the houses had interior cold water taps for sinks and the communal outside toilets were replaced by inside facilities, and by 1955 New Lanark was connected to the National Grid.

The Tenement Through Time exhibition was to have opened this spring but, as with many events, it has been postponed until later this year.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here