It was surely the most fateful and fanciful 48 hours in Scottish history and although the events were separated by centuries they reverberate to this day. There were tragedies, double dealings, legends created, unimaginable power unleashed, machinery constructed, demolished along with job and, oh, here also be monsters.

The days opened with the bells of St Giles' Cathedral ringing out on May the First in 1707, legally uniting Scotland and England as the Act of Union came into force. The tune the bells played was at the very least ambivalent about the newly-forged connection, Why Should I Be Sad On My Wedding Day.

The contemporary historian Simon Schama described it thus: “What began as a hostile merger, would end in a full partnership in the most powerful going concern in the world ... it was one of the most astonishing transformations in European history.”

Well, maybe, although the hostility to the conjoining is underestimated. However you view the creation of what was to be Great Britain there is no doubt it was vigorously and violently opposed by the majority of Scots.

Riots in Edinburgh and other Scottish towns in the months and years leading up to it had become a feature of everyday life. The Duke of Hamilton, who led the nationalist opposition (although the cad was actually in the pay of the English), was cheered along the Royal Mile as he passed each day in his carriage, whereas the Duke of Queensberry, who supported the deal, required round-the-clock protection from hostile mobs chucking not just epithets but anything they could lay their hands on.

When Daniel Defoe arrived in the city in 1706 in his day job as an English secret agent, he described “a Scots rabble is the worst of its kind”, while conceding that “for every Scot in favour of the union there were 99 opposed”.

Scotland had been all but bankrupted by the Darien scheme to build a colony on the plague-afflicted isthmus of Panama although as most of the population had nothing to lose, their level of poverty remained as crushing and deadly as it had before. It was the nobles and rich speculators, who had gambled and lost in the mad venture, who were hustling it through on the promise of a better time, mainly for themselves as they were to receive more than half of their losses returned.

The Edinburgh parliament represented Scottish opinion only in a theoretical sense, made up as it was of self-perpetuating noblemen and landowners, but this was true of all parliaments wherever they existed. By the eve of the Union there were 302 parliamentarians, some 143 hereditary peers, 92 "shire" or county commissioners, and 67 burgh commissioners.

The rough head count at the time reckoned that the majority of the parliament would be agin the deal, which is where blatant bribery was employed to buy votes and pay spies and agents provocateurs, £20,000 sterling (£240,000 Scots) of which was distributed by the Earl of Glasgow.

As Robert Burns famously put it, “Such a parcel of rogues in a nation” they were “bought and sold for English gold”.

By then, the Scottish and English thrones had been united under one monarch for more than 100 years, since the Union of the Crowns in 1603, when James Vl also became king of England when Queen Elizabeth died childless.

James was Mary, Queen of Scots' son, although he hadn’t seen her since he was an infant. The doomed Mary, taking advantage of May Day, wassailing and general drunkenness in Lochleven Castle where she was being held a prisoner in 1568, managed to escape and head south. She was heedless of her advisers telling her not to go to London and she ended up, of course, heidless.

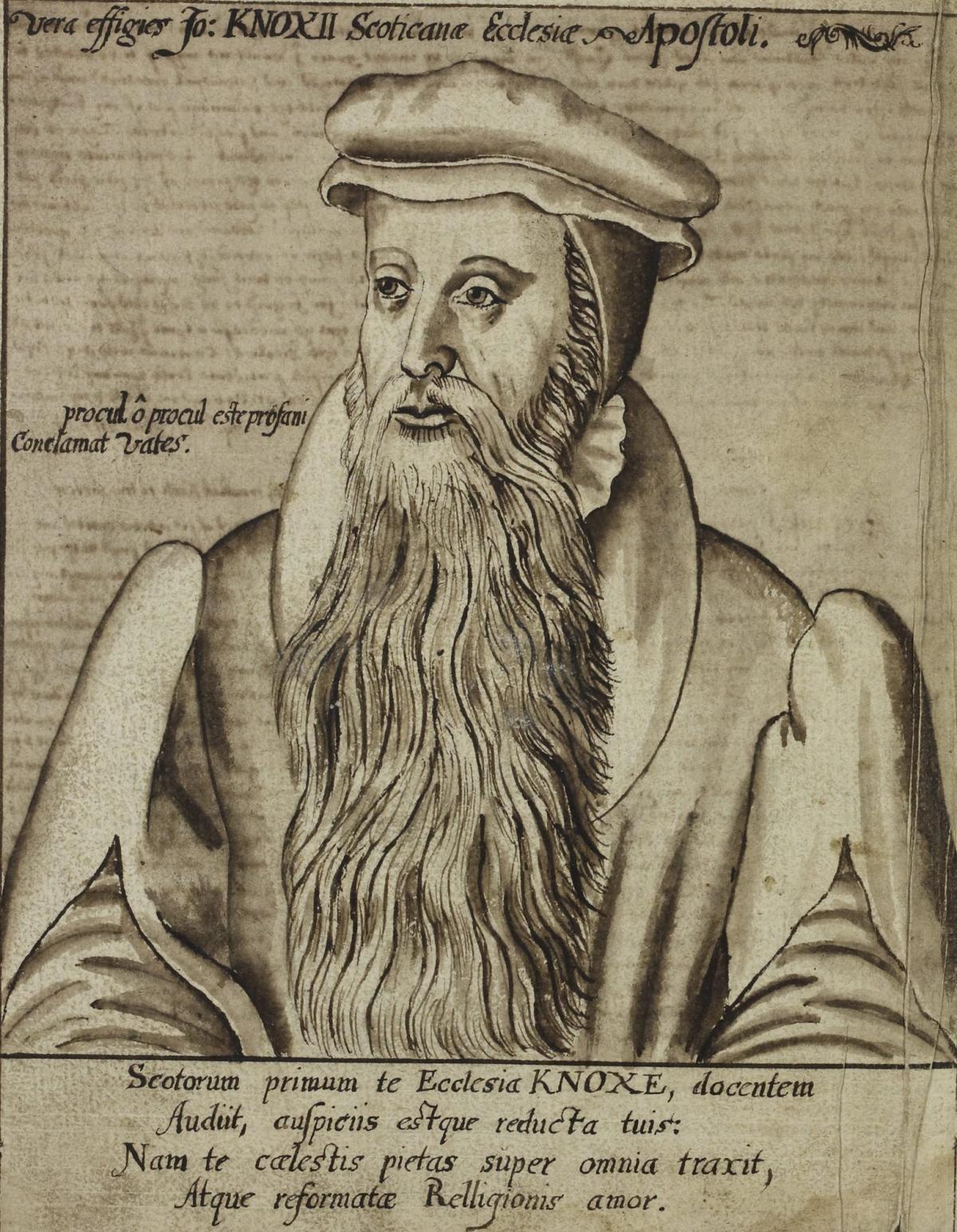

May 2, eight years earlier, had seen the return of John Knox from exile to lead the Scottish Reformation. And as Gandhi would probably have said had he been around to be asked: “I think that would be a good idea.”

Knox believed that having a woman ruler – as he blasted in his famous tract The First Blast of the Trumpet against the monstrous regiment of women – was a violation of the natural order. Following Mary’s escape from Lochleven he joined the chorus condemning Mary as an adulteress and murderess and for the rest of his life spoke of her as “that wicked woman”.

May 2 in 1611 was also the day the King James Version of the Bible was published in London.

There have been monsters throughout Scottish history, usually of the two-legged kind. On May 2 in 1933 while one of most evil in history was starting a reign of terror on his people by first taking over German trade unions, here we were looking to the north of the country and Loch Ness, not to Hitler, and the legend of the serpentine monster began.

There may have been local mutterings and sightings before but when the Inverness Courier ran a story about a large “beast” or “whale-like fish” it was christened Nessie. The writer was Alex Campbell, a water bailiff on the loch and part-time journalist, and the article covered an alleged sighting by Aldie Mackay of an enormous creature writhing about the water as she and her husband drove along the shore.

In Campbell’s words, “The creature disported itself, rolling and plunging for fully a minute, its body resembling that of a whale, and the water cascading and churning like a simmering cauldron. Soon, however, it disappeared in a boiling mass of foam.”

Not for long, however, because it was to reappear with regularity in the years that followed, to be photographed – although some of the shots were hoaxes or genuine misinterpretations of innocent logs and waves – and see surveys and expeditions camp on the shore for months, and to be written about until this day.

The latest "sighting" was in 2014 when Apple Maps showed a satellite image of what appeared to be a 30-metre-long monster, although it might just have been the wake of a boat, ripples caused by seals or floating wood.

On that same day in 1959, a monster capable of both destroying the world and powering it opened in southwest Scotland. It was the Chapelcross nuclear station on a former Second World War airfield near Annan, commissioned to produce weapons-grade plutonium for the UK’s weapons programme and also to generate power for the National Grid.

The plant was decommissioned in 2014 but the final demolition and site clearance won’t be complete until at least 2095, but more likely the new century. Hope you’re around for that.

On May 2 in 1963, the first Hillman Imp rolled off the production line at the new Rootes factory at Linwood. It was meant to compete with the highly-successful Mini, but it was hastily designed and badly executed. It was rear-engined and handled badly – some customers placed a bag of cement under the front bonnet to keep it stable – and it had an inadequate cooling system, gearbox and clutch problems, faulty chokes and a tendency to leak water. No surprise the Imp developed a reputation for unreliability.

It wasn’t all bad as it provided work in an industry-ravaged area although that was not to last and, in 1967, the company donated 100 Imps, painted green and white, for Celtic fans to drive to Lisbon to watch their team lift the European Cup.

After 12 years it was over – “Linwood no more” as the Proclaimers sang in Letter From America – when Chrysler, which had taken over from Rootes, closed the factory and, in its words, put an end to that “damned poorly-designed automobile”. And damned the 11,000 or so who were directly or indirectly employed by the company to the dole queue.

Another carmaker, Henry Ford, said that history is bunk. The future isn’t looking so bright either.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel