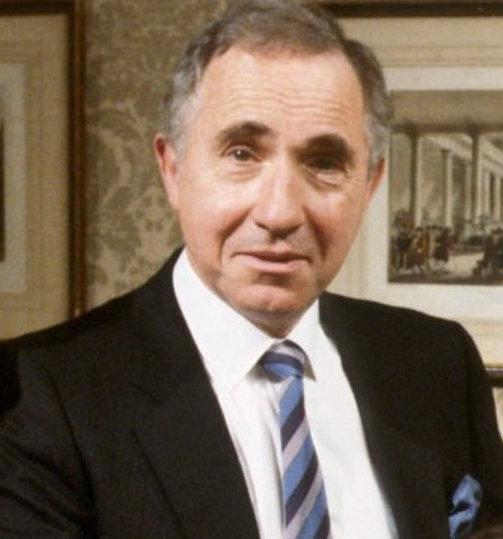

Lord Armstrong of Ilminster

Born. March 30, 1927

Died. April 3, 2020

Lord Armstrong, who has died aged 93, was the confidante and adviser to three prime ministers: all with very different characters but serving them all with respect and diligence.

His tact, diplomacy and patience were, however, often required. He was much involved in many major public events – notably, the famous ‘economical with the truth’ – in a court room in Australia in 1986.

A former embittered MI5 officer, Peter Wright, published his memoirs, Spycatcher, which the UK government alleged leaked confidential secrets.

Wright’s cunning defence lawyer, Malcolm Turnbull (later Australia’s prime minister) quizzed Armstrong ruthlessly and when asked the difference between a lie and a misleading impression Armstrong replied, “perhaps being economical with the truth.”

He immediately pointed out that the phrase was not his – but that of the 18th century philosopher Edmund Burke. The off-hand remark was to haunt Armstrong all his life.

In fact, he was known outside Whitehall as the original for the fast talking and manipulative Sir Humphrey Applebey in the BBC drama Yes Minister.

Turnbull directly compared Armstrong to Appleby and chose to refer to Armstrong in his summing up, “If he is an honest man, then he appears rather like a well-educated mushroom”. Later Armstrong described the experience as “the most disagreeable time”.

Robert Temple Armstrong was the only son of Sir Thomas Armstrong a former principal of the Royal Academy of Music. He attended Eton where he was a King’s Scholar and then read Classics at Christ Church, Oxford. In 1953 he was appointed private secretary to Reginald Maudling, the future chancellor of the exchequer and then served both RA Butler and Roy Jenkins when they were chancellors.

Armstrong’s quick mind and eye for detail marked him out as a high-flyer in Whitehall. So, it was no surprise when he was appointed principal private secretary to the new prime minister, Edward Heath, in 1970 (until 1974). His distinguished career saw him at the centre of government serving Harold Wilson from 1974 to 1975 and, as cabinet secretary, to Margaret Thatcher from 1979 and 1987.

It is thought he did not remain under Wilson as his secretary, Marcia Williams, wanted more control of the administration in Number 10. In 1975 Armstrong worked for the reforming Home Secretary Roy Jenkins until 1979. That year he became cabinet secretary and in 1983 head of the civil service under Thatcher.

Armstrong was the ultimate behind-the-scene-fixer. He played an important role in Thatcher’s bid for peace in Ireland. She entrusted Armstrong with the secret negotiations in 1981 (insisting that nothing was written down during discussions) which took place in the heated atmosphere of the time and after the hunger strikes. In Charles Moore’s extensive biography of Thatcher, he calls those Anglo-Irish talks, “Armstrong’s greatest legacy – that led eventually to the Good Friday Agreement in 1998.”

Armstrong was involved in many of the high-profile events of the era: he was with Heath throughout the negotiations to enter the EEC in 1973; he was taking the minutes when Michael Heseltine walked out of the Cabinet in high-dudgeon over the Westland affair. The Prime Minister then appointed Armstrong to conduct an inquiry into the sorry affair. Armstrong concluded that the Trade Minister Leon Brittan had leaked a letter damaging to Heseltine, without saying that Thatcher knew about the strategy.

Significantly, Armstrong was adamant that Thatcher should not give a knighthood to Jimmy Savile. His opinion prevailed until after he had retired.

Throughout his years as head of the civil service Armstrong passionately believed in the need for total secrecy within Whitehall. Leaking was a complete anathema to him and he took a robust line against anyone who talked to the media. He issued firm guidelines instructing civil servants that they were, “servants of the Crown. For all practical purposes the Crown in this context means, and is represented by, the government of the day.”

Armstrong was the archetypal Mandarin. Incisive, intelligent and able to weigh up important events and present them with succinct clarity. Under his management meetings were controlled and worked like clockwork. A minister who worked with him has written, “Robert really was a remarkable public servant, one of the best I have dealt with. Firm, honest, tough, but much warmer than most of the others.” Armstrong was always very proper in dealing with his prime Ministers. Despite seeing Thatcher two or three times a day he always addressed her as “prime minister” and she in turn called him “Robert”.

Armstrong remained passionate about music all his life. He was secretary of the board of the Royal Opera House and then served on its board. He was a very knowledgeable opera fan and regularly attended performances. His friendship with Edward Heath was firmly founded on their mutual love of the piano: the two often played piano duets at Chequers of an evening with little or no conversation.

On retiring Armstrong served in various capacities and was knighted in 1978 and made a life peer 10 years later.

In 1985 Armstrong married Patricia Carlow, and she survives him along with his two daughters, Jane and Teresa, from his first marriage, to Serena which was dissolved.

Alasdair Steven

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here