COLOURFUL fishing boats bob in Ullapool’s busy harbour, their colours offset by the whitewashed buildings that line the shore, a reminder of its long links with a once-thriving herring industry.

Loch Broom, either dark and brooding or postcard pretty depending on your luck, provides a perfect view for visitors to relish as they wait for the red and black colours of the Caledonian MacBrayne ferry to appear in the distance.

Most will have arrived in one of Scotland’s most treasured northwest coast spots by travelling the 32 miles of the A835 from Garve.

The twisting road will have swept them up and down hills, past Ben Dearg and Ben Wyvis, alongside the Black Water river, Loch Droma and past the Glascarnoch Dam.

Some might have stopped at Corrieshalloch Gorge, 12 miles east of Ullapool, parking just off the edge of the A-road to walk to the spectacular Falls of Measach.

Of those who make that extra effort, most will almost certainly have stood on the 82ft suspension bridge that spans the gorge and provides a perfect view of the waterfall.

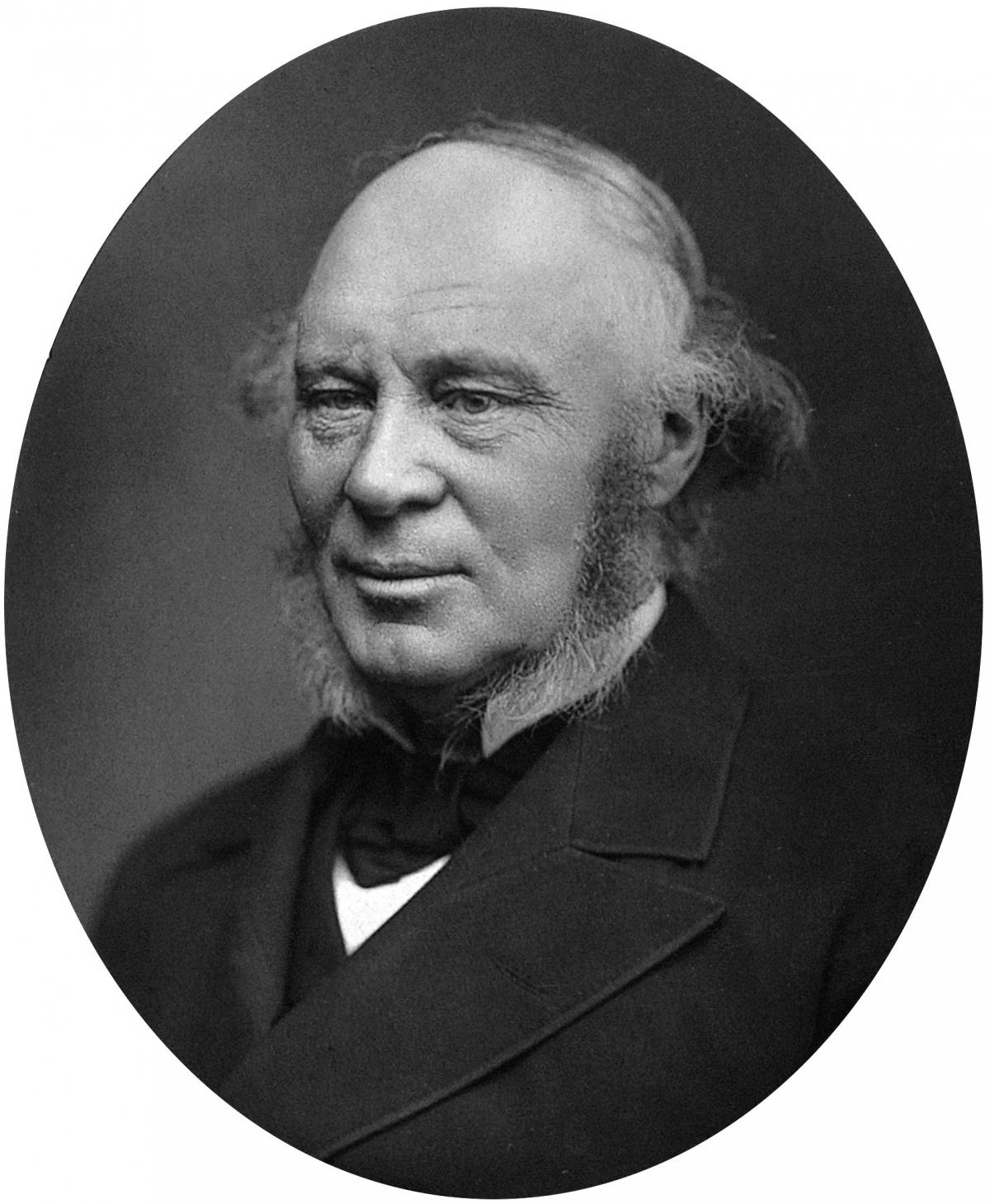

Constructed by pioneering engineer Sir John Fowler, joint designer of the Forth Bridge and who created the world’s first underground railway, the bridge sways gently as just six pedestrians at a time look over the 200ft drop.

READ MORE: Glasgow rail disruption as Highland cow blocks line between Busby and Pollokshaws West

An ingenious construction of wire-rope cables, pylons and suspension rods, Fowler's bridge has stood the test of time – yet another symbol of good old Victorian engineering prowess.

It is a skill for engineering which could, had history taken its own brief off-road detour, have completely transformed that far distant corner of Scotland.

For had Fowler and a group of visionary colleagues had their way, it would not have been just that busy, winding road crammed with caravans, motor homes, trucks and cars that would have brought visitors and business to Ullapool.

Instead, the route to that prized northwest corner, where tourists now flock to see glorious coastal scenery, dark lochs overlooked by dramatic hills and rolling moorland, might well have been via one of the most spectacular rail journeys in the world.

It is 130 years ago this year since an Act of Parliament paved the way for the construction of an ambitious but achievable rail link that could have transformed Ullapool and brought a host of potential economic and social benefits.

Devised by Fowler, his son Arthur and a group of well-heeled companions including Lady Mary Matheson of the Lews, widow of James Matheson, co-founder of Hong Kong-based conglomerate Jardine Matheson & Co and owner of the Isle of Lewis and much of Ullapool, the railway could have solved a longstanding problem: how to transport massive quantities of herring being landed by local fishermen to market as fast as possible.

Steamships took too long. Railways were new and fast. A railway, they believed, could have brought prosperity to desperately poor crofters and cotters, opened up the Isle of Lewis to new trade, and helped extinguish troublesome land raids and civil disobedience which had become an all too familiar element of island life.

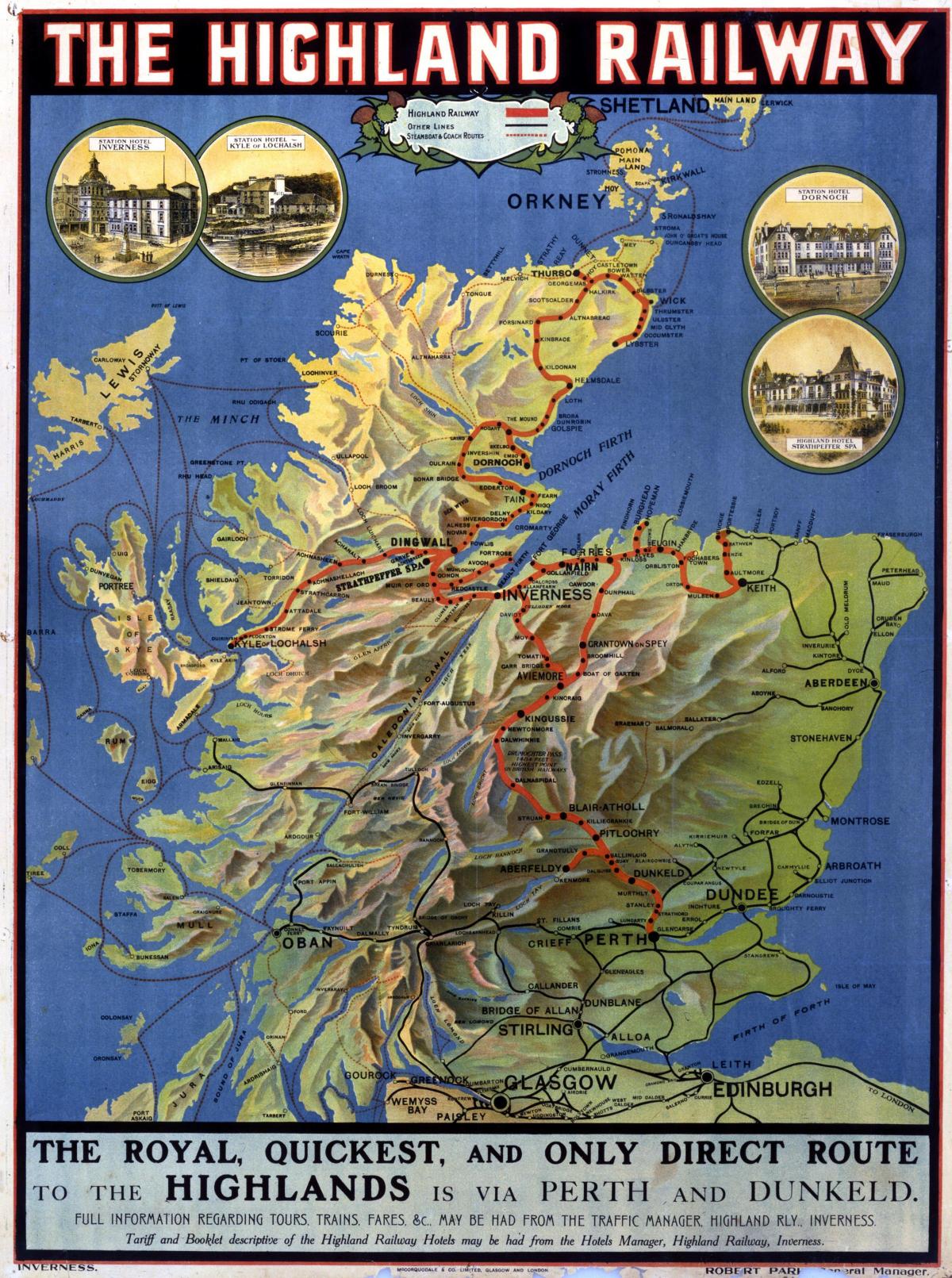

Branching off the Dingwall-to-Skye line slightly east of Garve station, the proposed track would have powered steam trains upland, following the road past the Black Water river, through the Glascarnoch glen and rising to 900ft towards Braemore Lodge and the estate owned by Fowler, already celebrated as one of Britain’s most acclaimed engineers.

If the scenery didn’t take the breath away from railway passengers, surely the prospect of a steep descent towards the head of Loch Broom would have.

Or, the engineers’ preferred option, a tunnel carved through the hillside which would bring them, blinking, into glorious sight of the mouth of the River Broom sprawling before them.

READ MORE: Scotland’s 10 best train journeys

Once in Ullapool, rail travellers would simply have stepped from their carriages at a terminus built at the junction of the town’s Shore Street and Quay Street, mere steps away from the ferry to the Isle of Lewis, and potentially one of the most magnificent settings imaginable for a railway station.

However, as a forthcoming book written by Andrew Drummond, the best-laid plans of even one of the nation’s most celebrated engineers was set to go horribly wrong.

And a combination of competition, lack of funds, divided communities and a frustrating lack of support from Westminster would eventually see plans stop, start, run out of steam and then hit the buffers for good.

“It was all a bit of guddle,” says Drummond, whose book, A Quite Impossible Proposal: How Not To Build A Railway, will be published this year.

“There were a lot of shenanigans between government, promoters, the Highland Railway Company and other people sticking their oar in.

“There was the extraordinary attitude of civil servants in London, who were very dismissive of the whole thing.

“In fact, the title of the book – A Quite Impossible Proposal – was one of the comments made by one of the chaps in London.”

The Ullapool-to-Garve railway proposal was the first of what would eventually become half a dozen railway schemes touted for the area during a boom time in Victorian engineering which unlocked areas of Britain which previously would have taken hours of discomfort by carriages and carts to reach.

While the prospect of a train to Ullapool might have tourists today regretting decisions of the past, its vision was not built around their needs, but in herring, crofting and poverty.

“The scheme for the Garve-to-Ullapool railway goes back at least 10 years before it was given Royal Assent in August 1890,” he says.

“The crofters and fishermen of Lewis and Skye had been in revolt. Crofters were invading land, taking it back for themselves and the government was sending troops in to sort it out.

“In the early 1880s, the government had become a bit anxious and the Napier Commission was tasked with looking into the social and economic problems around crofting and fishing.”

Centred on Stornoway, the fishing industry’s biggest problem was getting freshly-caught herring to markets in London, Liverpool and Manchester.

The idea of switching from steamers to steam trains captured the imagination of Sir John Fowler. Yorkshire-born, he was one of those Victorian masterminds who appeared capable of just about anything.

As chief engineer of the Metropolitan Railway in London, he created the world’s first underground railway and laid the foundations for routes which today form most of the London Underground’s Circle Line. In return, he was paid handsomely: the equivalent of almost £30 million in today’s money, leading to comments that “no engineer in the world was so highly paid”.

The money helped him to buy the sprawling 40,000-acres Braemore and Inverbroom estate near Ullapool, where, as well as the suspension bridge across Corrieshalloch Gorge, he put his engineering skills to work building Braemore House on a mountainside 700ft above sea level, from blue-coloured stone retrieved from a nearby quarry.

Surely if anyone could oversee the construction of 33 miles of railway track from Garve to Ullapool it had to be him?

“The line from Garve to Ullapool would have had three sections. The first, Garve to Braemore, would have been very straightforward,” adds Drummond.

“But at Braemore, there’s this steep descent to sea level before the final stretch to Ullapool, again fairly straightforward.

“The tricky part was going down the hill.

“There were all manner of exciting ideas involving both the north and south sides of the valley, but both were steep.

“The southside would have used tunnels and viaducts. It would have been a bit like a helter skelter, but if I have confidence in anything it would be confidence in Victorian engineers to do anything they wanted.”

While some huffed and puffed over the challenges of creating the line, others questioned the suitability of Ullapool as a harbour for the ships arriving to transport countless tonnes of herring.

“One inquiry (into the railway) said Ullapool was beset by rocks and reefs so ships could not possibly get in there, which clearly isn’t the case.

“But the really difficult thing wasn’t so much the engineering, it was getting the money together and the government did not want to help.”

Despite various commissions and committees to probe ways to improve the fortunes of poverty-stricken island and Highland communities, few positive suggestions were taken up and even fewer received funding.

If they wanted to push ahead, the proposers of the Ullapool rail link faced funding the £200,000 project themselves – around £20m in today’s money – or finding an established railway business willing to take it on.

“The Highland Railway Company virtually had a monopoly in the north and west of Inverness, and they were not keen on competition,” adds Drummond.

“They wanted to extend their line from Dingwall to Stromeferry, on to Kyle of Lochalsh. They didn’t want any other lines going to the west coast.”

Yet common sense and geography should have made the Ullapool route the more attractive. “Stornoway to Ullapool is 40 miles at most, but Stornoway to Kyle of Lochalsh is closer to 100 miles,” says Drummond.

If financial support was proving challenging, so too was getting everyone on board the Ullapool express.

Some simply preferred the Kyle of Lochalsh option, others argued that shifting herring stocks made it difficult to predict the best locations for a rail link.

“Lewis was practically riven down the middle,” adds Drummond.

Meanwhile, angry letters were exchanged in newspapers from both sides arguing for and against.

“The Act of Parliament of 1890 had a clause that if work wasn’t undertaken within three years, it would be null and void,” says Drummond.

While the Ullapool backers fumed, the Highland Railway Company pressed ahead with its Kyle of Lochalsh extension. The 12-mile section of railway took three years to build and opened in 1897 – due to the challenging landscape, it did receive government support.

“That was the galling thing. Someone else got some money but the engineering difficulties were just as bad,” explains Drummond.

Determined not to be beaten, the proposers of the Garve-to-Ullapool railway carried on. There were further attempts to achieve their dream in 1896, 1901, 1918 and 1945. Of course, none were successful, leaving the question: what might have been?

“The railway would have brought not just fishing trade through Ullapool but all the stuff that hangs off that,” says Drummond. “There was the potential for people travelling to and from work, the provision of education, and medical facilities might have been so much better.

“And, of course, opening up the railway would open up tourism earlier.”

Dr Iain Robertson of the Centre for History at the University of the Highlands and Islands, agrees the railway could have brought a long-lasting positive impact.

“It would have been a real tourist asset,” he says.

“Just as there’s the Glenfinnan Viaduct that has become a huge attraction, the line towards the head of Loch Broom would have been really spectacular.

“You can certainly imagine a steam train rumbling through the glens on its way to Ullapool.”

Parallels between opposition and debate over the Ullapool line might well be drawn with today’s controversial HS2 high-speed link between London and the north, he adds.

“The Garve-to-Ullapool line was very, very divisive – it’s a theme that runs through big railway developments wherever you find them. In this case you have a strong crofting culture, the area is allied to the Free Church, and there may be opposition to any attempt to modernise and change.

“People had a strong feeling for the land and for crofts – fishing was seen as something that was temporary.

“Herring shoals can come and go without any warning. And basing your economics on an unpredictable species like herring would have been risky.”

Drummond, meanwhile, believes Ullapool, with its scattering of whitewashed buildings at the end of a long, twisting road, could today easily have been reaping the benefits of a rail link and still retained its charm.

And if other railway proposals to open up sections of Lewis and Skye had also materialised, road congestion from too many tourists would certainly not have posed the same issues as they do today.

“The rail extension to Kyle of Lochalsh didn’t cause Mallaig to suffer,” adds Drummond.

“You can only wonder at what difference a railway to Ullapool might have made.”

A Quite Impossible Proposal: How Not To Build A Railway by Andrew Drummond will be published in September by Birlinn.

What might have been: the lines that were never built

A spate of railway proposals emerged at around the same time which would have transformed the northwest corner of Scotland.

Others would have created rail links between communities now booming thanks to the North Coast 500 road route.

One suggested a rail link between Achnasheen in Ross-shire and Aultbea on the shores of Loch Ewe while another proposed a connection on the Far North Line between Lairg in Sutherland with Laxford.

A further plan was lodged for a link between Culrain and Lochinver.

Meanwhile, the Hebridean Light Railway Company had plans for Skye and Lewis, with routes that would have transformed island life and tourism.

It suggested a line in Skye would have connected the port of Isleornsay with ferries at Mallaig, and another at the port of Uig on the northwest to link with ferries to Stornoway.

Another line was proposed between Stornoway and Carloway on Lewis, with branch lines at Breasclete and Dunvegan.

None, however, would be built.

The only one proposed was an extension of the West Highland Line from Banavie near Fort William to Mallaig. This was recently voted the greatest rail journey in the world and includes the iconic Glenfinnan Viaduct which featured in the Harry Potter movies.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel