IN June 1965 six bored boys, aged between 13 and 16, all pupils of a strict Catholic boarding school called St Andrew’s in the Tongan capital Nuku‘alofa, decided to go on an adventure. Taking two sacks of bananas, a few coconuts and a small gas burner, they “borrowed” a boat from a local fisherman and set sail for Fiji some 500 miles away.

That night they all fell asleep onboard, only to wake in the dark with the weather on the turn. Waves were crashing over them. They quickly hoisted the sail, but it was shredded by the wind. Then the rudder broke.

The small fishing boat began to drift. For the next eight days, the boys tried to catch fish and collect rainwater in the hollowed-out coconut shells. And then they saw an island, a 1000ft-high mass sticking out of the sea. This was the uninhabited island of Ata. The boys managed to guide the boat to this unforgiving lump of rock in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. And then they had to work out how to survive.

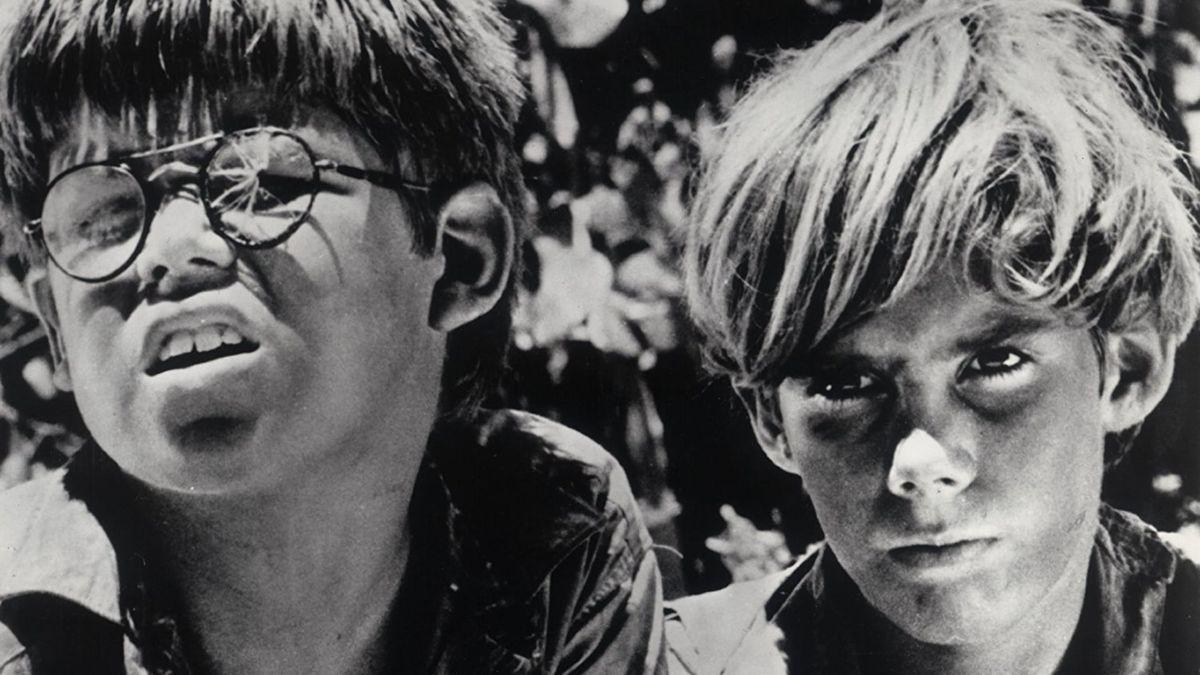

At which point we might think we know where this story goes. We have all read Lord of the Flies, or at least know the story about a group of schoolboys who end up on an uninhabited island (after a plane crash in their case) who go wild, argue, divide, form opposing tribes, and who, ultimately, revert to savagery and eventually murder.

“Man produces evil as a bee produces honey,” William Golding, the author of Lord of the Flies, would later suggest. In short, violence and destruction are in our nature. His 1951 novel is therefore a chart map of the descent of man (or boys in this case).

Except that isn’t quite what happened on the island of Ata. On Sunday, September 11, 1966, the Australian captain of a passing ship noticed burnt patches on the island’s green cliffs. Intrigued, he sailed closer and through binoculars he saw a naked boy who promptly jumped from the cliffside and started to swim towards the ship. He came onboard and told the captain, “My name is Stephen. There are six of us.”

In their 15 months on the island, the six boys hadn’t reverted to savagery. Rather, they managed to start a fire and kept it alight for more than a year. They drew up a roster for garden, kitchen and guard duties. They worked out a solution to resolve arguments. They survived storms and lack of water. When the captain found the boys, they were all in perfect physical health.

This story, a real story, is one of survival. But it’s also a story of co-operation, of boys working together, helping each other out, of finding a way through.

That’s why Rutger Bregman retells it near the beginning of his new book, Humankind. Subtitled “A Hopeful History,” it is a book that sets out to challenge the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves, one that suggests we are not as selfish and self-interested as we are told we are, that posits that our instincts are primed for co-operation rather than competition, that argues for altruism, that believes in the concept of human kindness. “It’s time for a new realism,” he writes. “It’s time for a new view of humankind.”

Rutger Bregman lives in Houten, “a small place in the middle of the Netherlands, a very boring provincial town,” he says, with his wife and a growing reputation. His last book, Utopia for Realists, argued for a universal basic income and a shorter working week. Last year he addressed the World Economic Forum and told the global elite that if they really wanted to address global inequalities, they could start by facing up to their tax avoidance. The real issue, he told them, was “taxes, taxes, taxes, and all the rest is bullshit”.

Bregman is an articulate thirtysomething whose book is a challenge to many of our preconceived ideas about humanity. In a way, he suggests, our current pandemic crisis is a perfect illustration of one of the main themes of his book. It’s the Ata story played out on a global scale.

“What we are seeing right now reminds me very much of this whole body of sociological research. Since the 1960s, scientists have known that in a moment of crisis it’s not everyone for him or herself. Actually, people co-operate really well.

“But, somehow, we forget this again and again. I was just reading about why Britain was so slow to go into lockdown and one of the reasons [given] was the public couldn’t handle it, that they would become tired of it. They underestimated the resilience of the public.

“This reminded me of what happened before the Blitz because that was exactly the same situation. The military experts thought the British people would go nuts once the Germans started to bomb the population. But pretty much the opposite happened. The keep calm and carry on spirit.

“And then they thought, ‘It must be British culture. We’re so special.’ No, it’s human nature. Exactly the same thing happened when they started bombing the Germans.

“Somehow elites make this mistake again and again. They think, ‘How will people behave?’ They look in the mirror, they see themselves, and they think, ‘What would I do? Well, probably I would panic and act really selfishly. That’s how most people will behave.’”

The sort of thinking, in other words, that means you get in a car and drive to Durham during a lockdown.

But that is not what most of us do, Bregman suggests. When Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in August 2005, killing 1836 people, the media was electrified by reports emerging from the Superdome where 25,000 people had sought shelter. Reports of gun shots, stories of roving gangs, of rape and murder. The chief of police stated that the city was descending into anarchy.

Months later, it emerged that none of this was true. Six people had died in the Superdome, four from natural causes, one from an overdose and one poor soul committed suicide. The police chief had to admit there had been no official report of a single rape or murder. Instead, people came from as far away as Texas to help. “Catastrophes,” Bregman writes, “bring out the best in people.”

It’s a theme he returns to in our conversation. “On 9/11 we have extraordinary accounts of altruism while the towers were burning. You literally have people saying, ‘you go first’ as they went down the stairs of the burning twin towers.”

In short, Bregman takes issue with the 17th-century view of humanity outlined by the philosopher Thomas Hobbes that we are driven by fear and self-interest. Veneer theory is the more contemporary description; the idea that civilisation is a thin crust on the surface of humanity’s worst instincts. Bregman thinks we are better than that.

At which point, you might be forgiven for simply saying, “look around, mate.”

“I think that we are not only one of the friendliest species in the animal kingdom, we are also clearly the cruellest,” Bregman accepts. “There is no other species that I know of that likes to lock up groups of other people and then exterminates them. If you think about wars and ethnic cleansing and all the horrible things human beings are capable of … I’ve never heard of a penguin that does that.

“I believe there is a real connection between our capacity for kindness and empathy and our most cruel behaviour, because so often we do these cruel things in the name of loyalty and comradeship and friendship.”

This is our Achilles heel, he says. We are co-operative and friendly, but only with those we recognise as being like us. Those who are presented to us as “other” are suspect. And once we see them as different, well, we know where that can lead – to concentration camps and the industrialisation of murder.

Bregman’s fascinating, very readable, broad-brush history ranges from our hunter-gatherer days to the present day. He examines the psychological experiments that have been used in support of veneer theory; the infamous Stanford university prison experiment which saw the volunteers who were chosen as guards begin to torture the “prisoners” and Stanley Milgram’s Yale University experiment in which normal people were found to be willing to give an electric shock to people even though they knew it was causing pain. Both experiments (and their findings), he suggests, were deeply flawed.

He also examines the reality of conflict rather than the Hollywood recreation. In war, he points out, most soldiers never fire their weapons. After the Battles of Waterloo and the Somme there was little evidence of bayonet wounds among the dead. “Most of these victims were victims of artillery,” Bregman suggests, “because it is psychologically much easier to push a button and have an explosion far away.”

Even so, we must still negotiate the black horror of the Holocaust. “I think there are a lot of mechanisms that we have to look at," he says. "On the one hand this capacity we have for tribal behaviour and doing things in the name of loyalty. So, Wehrmacht soldiers kept on fighting, not because they were brainwashed or ideological fanatics, but because they were fighting for their friends.

“But then it’s obviously not true for the fanatical SS Guards, right? So, you need a layered explanation for so many phenomena.”

Psychological distance is part of it, he says. “This whole process of dehumanisation where you look at other people and don’t see people but see animals, or things.

“The social psychology experiments of the 1960s tried to make the case that there’s a Nazi in every one of us just below the surface. I think that totally trivialised the actual historical phenomenon of the Holocaust.

“These things are possibilities, but they are at the end of a very long and dark road where evil becomes normalised and people become adjusted to things they should never become adjusted to and often destroy themselves in the process.

“Because this is another thing we know; that killing another person often kills something within yourself as well, which suggests to me that we’re not born to do that.

“We like sex because it’s good for us, we like food because it’s good for us, but with violence we know soldiers who kill someone else often come back with PTSD.”

For Bregman, then, humanity isn’t made of as many crooked timbers as we seem to think. And yet that’s how we see ourselves. Why?

“Firstly, you have to look at the systems of information we have and most of us consume daily news, and the news is mostly about things that go wrong. It’s mostly about corruption and violence and terrorist attacks, etc. And we know from quite a bit of research that people who watch the news become more cynical and a bit more depressed. There’s even a term for it in psychology: they call it ‘mean world syndrome’. I think that partly explains it.”

Secondly, he suggests, it's deeply rooted in the culture, in the Christian idea of original sin, and in Enlightenment philosophy. “And then you look at the current system we live in. You could call it the neo-liberal capitalist model. Well, what’s the central dogma of that? It’s that people are selfish, and we just have to deal with it, right?

“Then the question is, who benefits from this? And I think the answer is that those in power benefit. The cynical view of human nature is a really important legitimisation of hierarchy, because if we can’t trust each other, then we need hierarchy. We need people to keep us in check.

“But if people are pretty decent, we can have a revolution to a much more egalitarian kind of society.”

It’s maybe no surprise that Bregman is the son of a Protestant minister, though he himself is an atheist. “Sometimes I think religion can have terrible consequences, but if you meet my parents you will discover it can have pretty wonderful consequences and help people become better versions of themselves.

“And that’s partly what this book is all about. It’s about the performative power of ideas. Because if we have this selfish view of human nature, we create a society that brings out the worst in us.

“If we have a more hopeful view of human nature – and I think a big part of the New Testament is infused with this more hopeful view – then we can create a very different kind of society.”

How might that manifest itself? Bregman makes a case for participatory democracy, which advocates more citizen participation and greater community political representation than traditional representative democracy. It is now in place in 1,500 cities around the world, including Porto Alegre in Brazil. And yet Brazil, of course, is currently led by an authoritarian leader in Jair Bolsonaro.

“I see lots of reasons for pessimism,” agrees Bregman. “Especially if you live in the United States and Brazil. These ‘strong men’ are doing such a terrible job. I also think it’s very visual and it grabs our attention, so we think this is the biggest story that is going on in the world. And the problem with participatory democracy is that it’s very calm and quiet. Many people won’t have heard of it. Most journalists hate it because it’s really boring. It’s just people sitting together around a table, whether they’re left-wing or right-wing, young or old, and they have these sensible discussions while they drink tea. It’s terrible reality television.”

But in the end, he is arguing that boring can be good. And if we can believe in our goodness, we can improve things. There is a Dutch lay preacher in him somewhere.

Bregman argues his ideas are tougher than they are sometimes portrayed. “People think, ‘Oh, this guy has written this nice and happy, warm book about the power of kindness and how you should follow your intuition.’ Well, actually, I’m also arguing for the opposite. I’m also arguing how intuition can lead us astray.

“If you follow your intuition you would never build a prison system like they have in Norway where they treat criminals with kindness. That is not what my intuition says if you have a rapist or a murderer. But it is the most effective prison system in the world.

“And that goes back to the other point; what it means to be a realist. I figure that’s the central objective of the whole book. To redefine that.

So often we say, ‘Oh, you’re too idealistic, you’re too hopeful, just be a realist. We equate realism with cynicism.

“We need to move to a very different definition of what it means to be a realist.”

Humankind: A Hopeful History, by Rutger Bregman is published by Bloomsbury, priced £20.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel