My memoir Starchild has been considered “timely”.

This is well-intentioned but, equally, an unsettling reaction. A few years back, publishers were reluctant to take a chance on the book, until it fell across the desk of an American publisher who, unbeknownst to me, had an adopted black daughter.

Suddenly, within a matter of weeks, racism and anti-racism are the ‘buzz’ words of the times, and my story of growing up with my black African brother Frankie in Scotland, has finally sparked some interest. But I feel dismayed at the tragic circumstances which have led to that interest.

Until a few weeks ago, I had to explain that my parents were ‘brave’ to have adopted my brother in1968, during the height of the American Civil Rights Movement, and in the same year that Martin Luther King was assassinated. Images of terrifying riots filtered across the Atlantic to the UK then, just as they have been doing now. Frankie had been reluctantly given up for adoption by his Ugandan mother, a visiting student, and, in late 60’s, he was deemed a “hard to place” child, but my parents took a quiet anti-racism stance and adopted him.

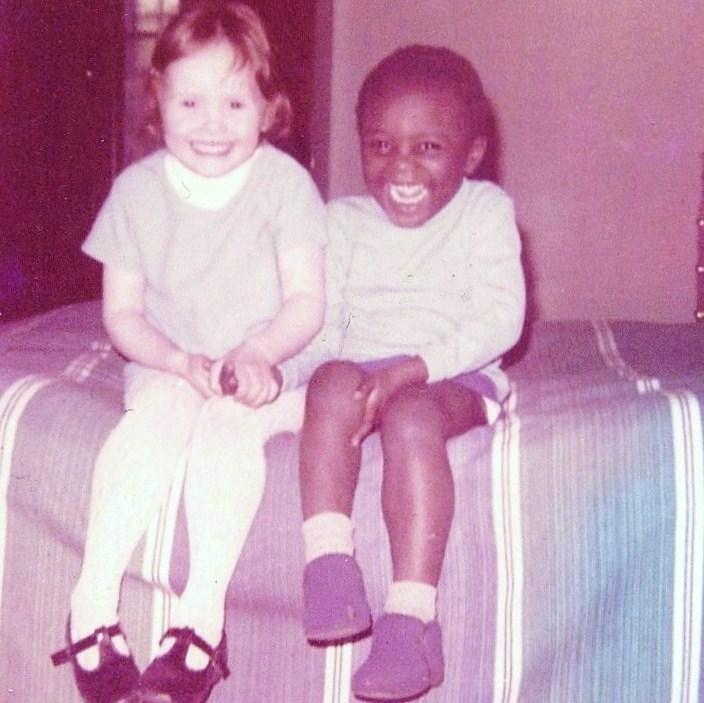

With only weeks between us in age, Frankie and I were pushed around Glasgow in a twin pram. We were an unusual sight and aroused much curiosity; few had seen transracial adoption at the time.

Now, this story which began in the late 1960s, has become a story for today.

What has changed? Sadly, in many ways very little, it seems.

Frankie was my twin in every sense of the word but, tragically, he died in an accidental house fire, aged 27. I was devastated. However, through a twist of fate, 18 years later, I travelled to Uganda and miraculously found his biological family. It felt like I had found a part of my own lineage. Overnight, I ‘inherited’ three new brothers. Frank and David live in Uganda, but Paul now lives in Minnesota, minutes away from where George Floyd was murdered. No strangers to everyday racism, Paul and his family now exist in a permanent state of fear because of recent events. Paul says this has brought back childhood trauma from his days of living under the abusive regime of Dictator Idi Amin in Uganda.

The world is glimpsing the reality of racism, and people everywhere need educated about its history. I just pray that the present events bring about some genuine change, and are not only a temporary noise while the world is watching for five minutes. I hope the energy can continue constructively past all the social media posts without it becoming diluted.

I know there has been racism in Scotland. I have been there when a knife was wielded in front of my brother because of the colour of his skin. I remember how we left bars and clubs because we knew we were in a hostile environment. Frankie, too, was often arrested for crimes he did not commit, because he was black. He never looked for trouble, but sometimes it found him.

But Frankie was also shown a great deal of love and respect in Glasgow. He had friends who would have defended him to the death. He did not have a chip on his shoulder, but maintained his smile, his charm, his humour and his hope that people could and would drop their colour barriers. He was a very popular person, and when he died that untimely death more than 800 people came to his funeral.

Details of the horrific history of the slave trade on which so much of Glasgow is built, and the daily reports of the abuse of black people everywhere today are very, very difficult to see and hear, but I am glad these issues are being addressed at last. But neither do I think we need to shame and divide this country. Dismantling the country isn’t going to help anyone.

Some strong, calm black voices that know what they are talking about are finally being given a platform. What we do not need is ill advised rhetoric, misguided ‘white saviour syndrome’, or even inverted racism which would only lead to more separatism and destruction.

There is a lot to be said for leaving the past where it belongs. If we want to change our cultural story we have to alter the story we keep telling ourselves about who we are and how life is. We have to educate our children and ourselves in a new way and reimagine ourselves with new ideas and visions about what it means to be human today and how we share this planet.

Experiencing true identity has nothing to do with the colour of your skin. Perhaps we are being called to expand our consciousness and free humanity from its old paradigm of fear, separations, anger and violence. Many yearn for a more peaceful expression of life with more equality. Perhaps as a human race, we are outgrowing the old ways. This creates social stress. Anxieties are heightened which feeds extremism.

Right now, we are gathering information, assimilating and beginning to articulate a growing sense of unease at the way we have been going about things. The blinkers are coming off. And, so now, perhaps the real work can begin.

In amongst the pain, stress and angst of the present situation, there are positive stories of anti-racism just waiting to be heard; stories like mine. My love for Frankie knew no boundaries of any kind, nor his love for me. And there are acts of courage, love and devotion taking place in many places which are not necessarily making the news. Some of these stories might help us heal and realise that we are all much more connected than we might believe.

So, perhaps my book is ‘timely’. It honours the deep love and connection between a black child and a white child. I hope it can be read by people of all colours without prejudice or racially motivated judgment. Otherwise we have learned nothing.

Michaela Foster Marsh is the author of Starchild and the founder of the Starchild charity which runs several projects for young people in Uganda

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here