Scotland has failed. Last week we were once again given a chance to have a grown-up talk about foreign interference in our politics.

We did not take it. As Westminster’s Intelligence and Security Committee published its long-delayed Russia Report, our tribal politicians, with a few worthy exceptions, dived in to their trenches and mortared their enemies with jibes as easy as they were dumb.

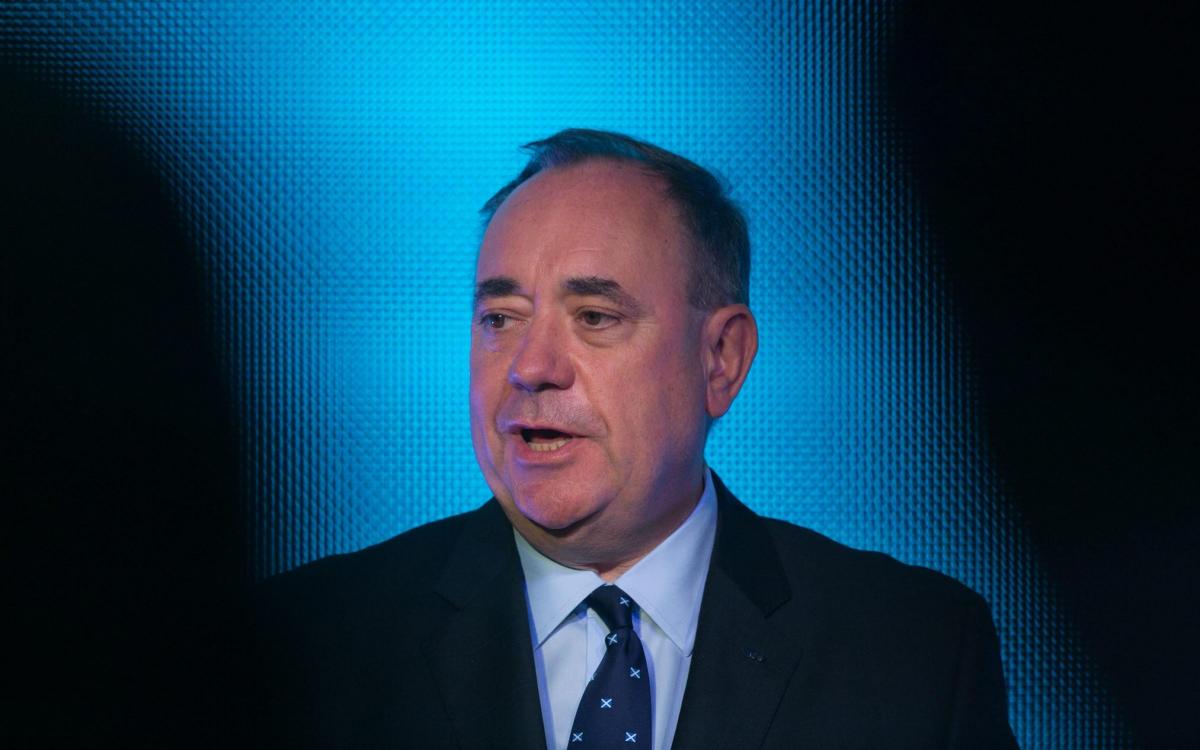

The SNP has questions to answer about Alex Salmond’s show on a Kremlin propaganda channel, yelled Tories in suspicious unison.

Conservatives, retorted an equally well-rehearsed chorus of nationalists, must come clean about their funding from rich Russians and David Cameron’s plea to Vladimir Putin to get the indyref on the agenda at 2014’s G8 summit.

Like all the best propaganda, these barbs stung because they were, like old true-life TV movies, “based on fact”.

READ MORE: Russia and the Scottish question: A timeline

After all, the current authoritarian regime in Russia really has elbowed its way in to our public life – even if smart people quibble about by how much, to what end and to what effect.

But a bigger truth got lost as insults flew across Scotland’s constitutional frontline, as we retreated to politics-patter-as-per-usual: that nobody, no party and no cause is immune to outside forces which would wish to use them for their own ends.

It is worse than that. These hyper-partisan responses, the finger-pointing and the digital yaboos, are not a sign of resilience to foreign interference: they are a symptom of vulnerability.

Putin’s government – as expert after expect has warned for years – has a tactic, a familiar one. It weaponises our existing divisions or – as the Russia Report called them – “wedge issues”. And “issues” do not get more “wedge” than the Scottish question.

Scotland is a big story, a big international story, and one that is not happening under a Perspex dome. What we do has impact elsewhere. And, yes, a whole variety of bad actors – not just Vladimir Putin – can affect us.

Our politicians, our media, our social media and our commentariat sometimes seem to revel in Russia as a political bogeyman, whether they think it is real or imagined. So this week we got all the usual Twitter jokes about MI5 agents and all the usual breathless and sometimes partisan reporting, some of it under naff faux Cyrillic headlines.

We should start thinking about defence, how to make our society, our economy and our democracy less vulnerable to outside meddling. And not just from Russia, and not just how intelligence agencies deal with what they call “hostile states”.

That is because Vladimir Putin is not forever. And it is also because other leaders elsewhere, not least China and rival Middle Eastern powers, are learning some of his government’s meddling tricks – and developing their own.

Other nations, some, like Estonia, smaller than Scotland, have built resilience. We can too. At the risk of sounding corny, we should start a national conversation about how to do so. This is not a job for spies and spy-catchers. It is for all of us.

Some of the things we meed to talk about are going to make us uncomfortable: our ignorance of the rest of the world; our complacency about dirty money; our degraded political discourse, our social media radicalisation; our institutional and regulatory over-reliance on good faith.

The Russia Report gives us a few starting points for some solutions. The document was ostensibly about Russia but really about Britain. Looking at Russia’s offensive capability had forced its authors to reassess the UK’s defences. They were found wanting. We do not know much about the scale of interference – beyond what everyone can see in the public domain – because nobody in power decided to take a close look.

“It has been surprisingly difficult to establish who has responsibility for what,” the report concluded. “Overall, the issue of defending the UK’s democratic processes and discourse has appeared to be something of a ‘hot potato’, with no one organisation recognising itself as having an overall lead.”

This should spark a reasonable discussion over whether the UK – or a future independent Scotland, for that matter – would need a powerful, independent public office to oversee things like campaign and party finance or political advertising .

But democracy is too important to leave to politicians or watchdogs or spies. The Russia Report said Kremlin interference was the “new normal” and it raised vulnerabilities across society.

It rehearsed the tactics of meddling: dark or dirty money in politics and our financial system; cyber attacks; and disinformation through covert social media and state propaganda channels. In short: lolly, leaks and lies.

READ MORE: Russia report: The key points from the ISC report

After years working in the former Soviet Union, Joanna Szostek, a lecturer in political communications at Glasgow University, has seen these three vulnerabilities before. “The most serious types of foreign interference are, in order, foreign states directly buying influence from politicians and parties (by offering, cash, gifts, business opportunities or other perks); ‘hacking and leaking’ which can shift the news agenda at critical moments and influence the way a lot of people vote; and covert operations on social media which may spread false information or promote division,” she said.

“Each type of interference obviously needs its own solutions.”

So what might they be? There is a lot of discussion to be had on this and no newspaper article can cover all its aspects. So here we’ll stick to the basics.

Take money first. “Transparency, auditing and journalistic scrutiny of where politicians and parties are getting their money from is crucial,” said Szostek. This, of course, is easier said than done. Journalist and writer Peter Geoghegan has been digging for years into the UK’s weak defences on political funding. Next month he publishes a new book, Democracy For Sale: Dark Money And Dirty Politics. Geoghegan reckons Britain’s political finance rules are based on what sounds like an old British sense of fair play.

“What we are relying on is good chaps acting like good chaps,” he said. “The maximum fine for breaking electoral law in the UK is £20,000. In America you can go to prison. Here you get a slap on the wrist. It is just the cost of doing business.”

Geoghegan used to think that Britain was more resilient than America because it has less money flushing through his politics. Now he thinks it is the other way around. “You can buy you a meeting with a Cabinet minister for £10,000,” he said.

“It is as cheap as chips.”

A parade of Conservative ministers and politicians have taken money for their campaigns from figures with past links to the Russian state. There is no suggestion any individual has done anything illegal or improper. But it’s worth thinking of the potential dangers here, and again, not just about Russia.

Then there are wider issues about Britain’s vulnerabilities to dirty money. The Russia Report references “laundromats”, the huge UK and international machinery used to wash filthy lucre coming out of various countries whose people are being ripped off. This is not just a problem for the City or for Westminster legislators.

Scottish white-collar professionals sometimes provide key services for the laundromat, including providing shell companies to conceal ownership and avoid tax. Kleptocrats have an army of little helpers in nice suits, lawyers, accountants, company formation agents and PR specialists. (It is not just the money that is laundered; reputations are too). Is there a role here for professional bodies to up their game on raising awareness of bad actors, state or otherwise?

“Hack and leak” campaigns might be a Russian speciality. But, again, we cannot assume they will only be carried out by Russia, or even state actors. “For cyber attacks, this solution is mainly a question of putting good IT security systems in place to protect sensitive information,” says Szostek. True.

But how does our politics and media bubble deal with a “hack and leak”? Typically, such an operation will vomit a mix of real, false and misrepresented information through old-school propaganda channels and mass fake social media accounts. Is our politics mature enough not to fall for spun kompromat from a foreign state actor when it is oh-so-tempting to do so? Are our politicians and journalism leaders getting any training to spot the talking points of overseas regimes or identify their fingerprints on “hacks and leaks”?

The new online threat is the one we know least about. Twitter and Facebook have taken down pages and accounts linked to several state actors, not just Russia. Experts have tracked disinformation campaigns in Scotland, notably a Kremlin operation to try to discredit the results of the 2014 indyref. But analysts have also concluded some suspicious online activity is indigenous, so-called McBots.

“Dealing with online disinformation is perhaps hardest, because it’s extremely difficult to identify sock-puppet accounts on social media and we rely heavily on Twitter and Facebook to do this for us,” said Szostek before suggesting better online literacy at school.

However, it is not just children who need to learn to spot the talking points of bad faith actors, from hostile states or otherwise. Late last year, a General Election candidate and now MP was suspended from the SNP for sharing anti-Semitic content. It was from Sputnik.

A lot of political polemics revolves around this channel and its sister outlet RT, the former Russia Today, where Salmond still has a show, albeit with minuscule ratings. Labour this week called for them to be taken off the air. Others fear that might spark tit-for-tat reprisals on free media in Russia.

Szostek stressed their very public nature – and regulations governing broadcasting – make RT and Sputnik less of a threat than dirty money, “hack and leaks” or online disinfo. But they are part of the disinformation machinery. And other state actors are also investing in similar tools.

Here is just one “red flag” that might be worth raising about such media in Scotland. There are two list-only tickets being proposed for next year’s Holyrood elections.

One, a pro-UK slate, is being fronted by George Galloway, a regular presenter on RT. The other list-only alliance, which backs independence, features Tommy Sheridan, who writes for Sputnik.

Both Galloway and Sheridan have had long political careers as socialist firebrands which transcend those jobs. But they also both echo key talking points of Russia’s current government, including on last week’s report, on Russian outlets. So, are we going to talk about this?

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel