“THE first time I smelt Jap was in a deep dry-river bed in the Dry Belt, somewhere near Meiktila. I can no more describe the smell than I could describe a colour, but it was heavy and pungent and compounded of stale cooked rice and sweat and human waste and ... Jap”.

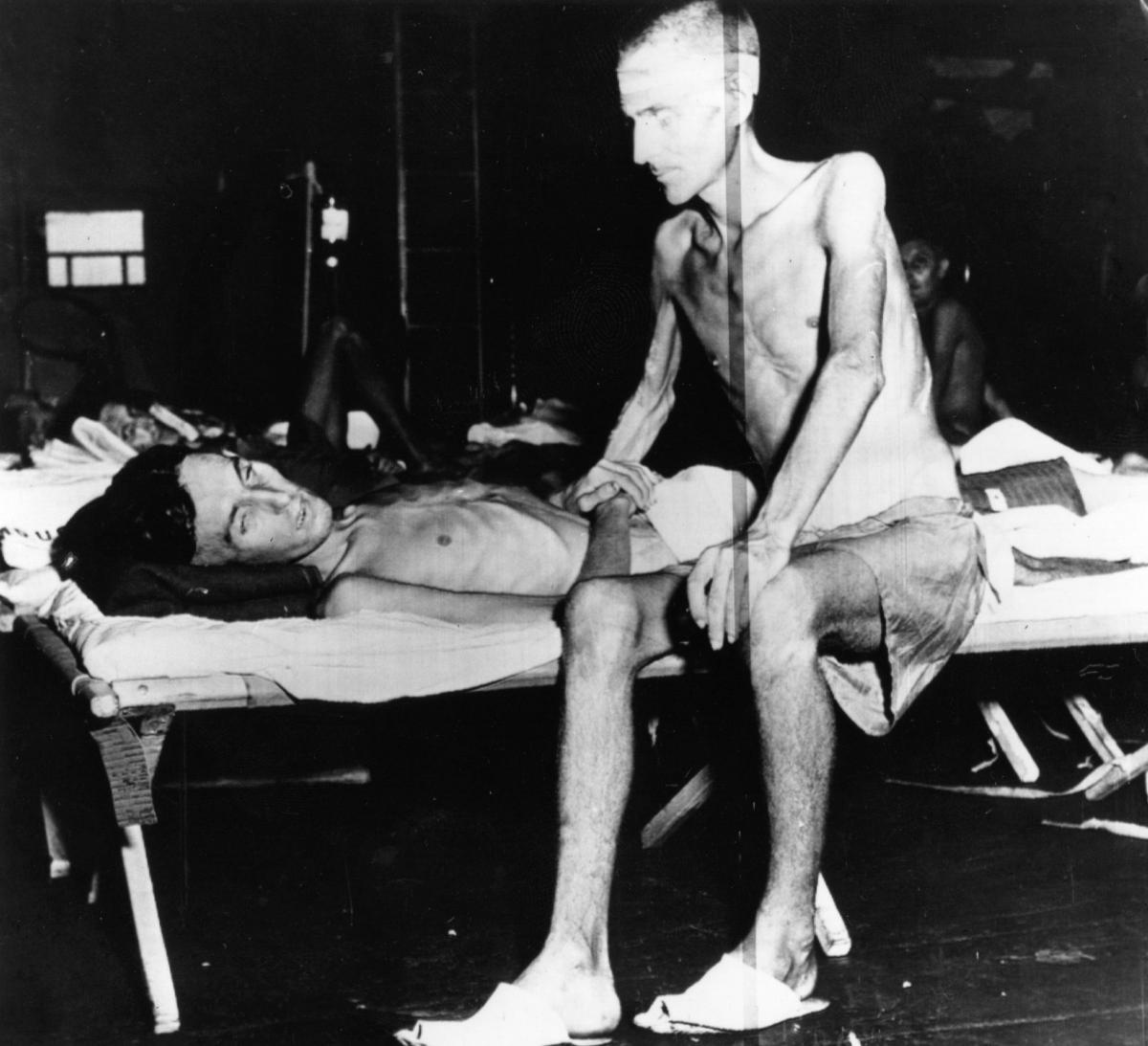

Burma, 1945. George MacDonald Fraser, 19, was a private in 9th Border Regiment, part of 17th Division, which itself was part of the massive 14th Army under General Sir William Slim. America, Britain and France were building up their forces for a concentrated assault on Japan, “the last enemy of democracy”, the tables having decisively been turned on Hitler.

In later life George would become a journalist – he occupied the deputy editor’s chair at this very newspaper – as well as a bestselling author, creator of the Flashman novels. The words quoted above form the opening to Quartered Safe Out Here (a phrase borrowed from Kipling), his riveting memoir of his time in Burma.

Until 1941 the conflict had essentially been a European one, but when Japan inflicted severe damage on the US Pacific Naval Fleet at Pearl Harbor, in Hawaii, that December, the war became a worldwide one. The US and Britain declared war on Japan.

The Japanese forces preceded to take Malaya, Hong Kong, Manila, and then Singapore, which was strategically important to the Allies. Churchill had urged General Sir Archibald Wavell, Supreme Allied Commander in the region, to ensure a fierce resistance there: “There must at this stage be no thought of saving the troops or sparing the population. The battle must be fought to the bitter end at all costs ….” But his words were to no avail.

British Burma was also taken by the Japanese after a prolonged action. Allied forces under Slim and huge numbers of refugees then embarked on a two-month long retreat to safety in India. “Slim conducted his retreat with some skill,” writes Max Hastings in All Hell Let Loose, his history of the Second World War. “But the Japanese now occupied Britain’s entire South-East Asian empire, to the gates of India”. Japan’s Asian conquests in 1941-42, he adds, “shocked and appalled the Western Powers”.

One of the Scots involved in the action in Burma was a young man named Eric Yarrow, who at the time was in the Royal Engineers; he would later run the family shipbuilding company in Glasgow. Writing in his memoirs, A Few Memories, Yarrow recalls: “At the start of the retreat, it was soon evident that the Allied forces were up against a well-trained, well-equipped Japanese army who had already been engaged in jungle fighting with the Chinese.

“There was an early disaster when the bridge over the Sittang River was blown up with two-thirds of the 17th Division on the wrong side of the river. When Rangoon [the Burmese capital] fell shortly afterwards, there was one objective – to hold up the advance of the Japanese into India until the monsoon had broken. This was, in fact, achieved, although it was a humiliating defeat”.

One of Yarrow’s assignments during the long retreat were to blow up bridges “and, more ironically, blow up ships of the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company built by Yarrows; it was quicker to blow them up than to build them!”. When he joined Yarrows after the war, he asked – tongue in cheek – his manager, “What about a commission on this new order we have received from the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company to replace those that I sank?”

“Why the hell did you not sink more?”, the manager replied.

All that Yarrow carried out from Burma were his revolver, a water container, an empty brandy flask, a battered old camera, and a towel with which to mop up sweat. The trek took place over mountainous country and across the Kabaw valley, “one of the unhealthiest parts of the world, described by a Chief of Staff as where ‘death drips from every leaf’. On reaching the Imphal plain, conditions were very rough for the monsoon had broken and accommodation had to be made from jungle materials, mostly bamboo and branches, in pouring rain”.

Despite its triumphs Japan did not have everything its own way. There were two key sea-battles with the Americans in May-June 1942. The first, in the Coral Sea, was a draw; the other, at Midway, resulted in a heavy defeat for the Japanese. The Americans invaded Guadalcanal in early August, and finally secured it in early February the following year.

By the time George MacDonald Fraser was in Burma, Japan’s fortunes on land had taken a turn for the worse.

“I had never seen a live Japanese at this time”, he writes in the first page of his book. “Dead ones beyond counting, corpses sprawled by the roadside, among the huts and bashas of abandoned villages, in slit-trenches and foxholes, all the way, it seemed, from Imphal south to the Irrawaddy.

“They were what was left of the great army that had been set to invade India the previous year, the climax of that apparently irresistible tide that had swept across China, Malaya, and the Pacific Islands; it broke on the twin rocks of Imphal and Kohima [where 30,000 Japanese were killed], were Fourteenth Army had stopped it and driven it back from the gates of India. [I imagine that every teenager today has heard of Stalingrad and Alamein and D-Day, but I wonder how many know the name of Imphal, that ‘Flower of Lofty Heights’, where Japan suffered the greatest catastrophe in its military history? There’s no reason why they should; it was a long way away]”.

He continued: “While I was still a recruit, training in Britain, this battalion had fought in that terrible battle of the boxes [defensive positions], and their talk was still of Kennedy Peak and Tiddim and the Silchar track, and ‘duffys’ – the curious name for what the Americans now call fire-fights – in the jungles and on the khuds [jungle hills] of Assam. There they had fought Jap literally to a standstill, and now we were on the road south, with Burma to be retaken”.

A key role in the campaign to retake Burma was played by special forces known as the Chindits, who were led by Major-General Orde Wingate DSO. They “fought behind enemy lines in northern Burma during 1943 and 1944 …. and were unconventional due to their total reliance on airdrops for their supplies and complete dependence on wireless for communications”.

Operation Loincloth, the first long-range penetration operation staged by 77 Indian Infantry Brigade, as the Chindits became known, took place in 1943 and saw them reach 1,000 miles into amid the Japanese lines succeeded in “carrying out a prodigious programme of destruction”, damaging railways and killing the enemy, though at high cost to themselves. The second, Operation Thursday, carried out the following year, was bigger and even bolder, but Wingate himself died in a plane crash on March 24. He was 41, and had been distantly related to Laurence of Arabia.

The Glasgow Herald said of Wingate that “he was the first man to match and outwit the Japanese at their own methods of jungle warfare”. He had been “hailed by some as ‘the new Lawrence’, he has been described by others as ‘a man of legends’, ‘a dreamer and man of action in one’, ‘a brilliant, puritan fanatic’, ‘a genius of the desert’, and ‘a Cromwellian captain’.”

His wife, Lorna Paterson, came from a prominent Aberdeenshire family and had been educated at St Leonard's School in St Andrews.

At the point when George MacDonald Fraser was in Burma, no-one knew when the war in the Far East would come to an end. (The atomic bombs would not be dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki until August). Some speculated that the war might have to be taken onto Japanese soil, as had happened in Germany.

A flavour of what it was like be an ordinary soldier seeking to reclaim Burma from the Japanese, a formidable enemy, comes in this passage from his book: it is worth quoting at length.

“What I had been trained for”, he writes, “was to be an obedient cog in the great highly-disciplined machine that was launched into Europe on D-Day. That would at least have been in civilised countryside, among familiar faces and recognisable environment, close to home and the main war effort, in a campaign whose essentials had been foreseen by my instructors. The perils and discomforts would have been no less, probably, but they would not have been unexpected.

“It is disconcerting to find yourself soldiering in an exotic Oriental country which is medieval in outlook, against a barbarian enemy given to burying prisoners up to the neck or hanging them by the heels for bayonet practice, among a friendly population who would rather turn dacoit than not, where you could get your dinner off a tree, be eaten alive by mosquitos and leeches, buy hand-made cheroots from the most beautiful girls in the world,… wake in the morning to find your carelessly neglected mess-tin occupied by a spider the size of a soup-plate, watch your skin go white and puffy in ceaseless rain the like of which no Westerner can imagine for sheer noise and volume ….”

It seemed, he added, a terribly old-fashioned kind of war. There was a strong sense of isolation out there, too; perhaps this came from being called The Forgotten Army – “a colourful newspaper phrase which we bandied about with derision; we were not forgotten by those who mattered, our families and our country. But we knew only too well that we were a distant side-show, that our war was small in the public mind beside the great events of France and Germany”.

Max Hastings writes that Slim’s army, which was dominated by Indian troops and included three divisions recruited from Britain’s African colonies, was larger than Japan’s: 530,000 men to 400,000. Furthermore it was supported by powerful air and armoured forces. Air-drops by US planes were a key factor in Burma’s mountainous and densely-vegetated terrain.

As the Burma Star Association records, the army launched a successful offensive down the Arakan Coast at the beginning of the year, followed by a major advance deep into central Burma. The soldiers retook Mandalay on March 20 after a battle that had lasted two days short of a fortnight. Rangoon itself was reclaimed on May 3.

“Burma Trap Closing on Japanese”, the Glasgow Herald reported on May 4, next to the dominant story that day, which had as its headline, in bold capitals, ‘Reich crumbling to its Doom’.

The Burma story began: “The fate of the Japanese still resisting in West Burma has been sealed with the entry yesterday of Allied land forces into Rangoon, the capital of Burma, and the capture of Prome, 178 miles to the north-west.

“A few stragglers may filter through the Allied line running down the Mandalay-Rangoon railway, but the bulk of the Japanese in the Irrawaddy Valley and the Arakan coastal area are cut off … Rocket and cannon-firing strafing planes of Eastern Air Command took a big toll of Japanese transport and materials as the enemy, fighting against time, strove desperately to remove accumulated stocks from Rangoon … The swift advance had compelled the Japanese to move vehicles and supplies by daylight to prevent their falling into British hands.

“Without air cover and in country ideal for low-level strafing, the enemy paid a high price. Pilots said that there was a trail of burned-out and wrecked transport stretching three miles southwards from Pegu on a main escape route”.

In a leading article the paper observed that when Rangoon fell in the spring of 1942 it had seemed unlikely that it would be recovered by means of a land campaign, yet that is exactly what had happened.

“The battle for Burma began as an infantry battle; it is ending as such”, the leader continued. “It is true that it was conditioned by a wise exercise of sea power in the early stages, and by the superiority of Allied naval forces towards the end.

“It is also true that the land offensive was supplied and sustained by air power from the date of the Wingate expedition. But Burma was a ‘grudge fight’, in which the 14th Army proved to itself and to the world that the Japanese could be beaten on ground of their own choosing, and by methods not greatly dissimilar to those which confounded us three years ago”.

Burma was the longest British land campaign of the entire conflict, having begun with a defeat and ended with a victory and the demise of Japan's imperial ambitions.

Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Allied Commander, South-east Asia, announced in an Order of the Day that though isolated pockets of the enemy remained, their doom was now sealed. “You have killed 97,000 Japanese and inflicted 250,000 casualties”, he informed the 14th. “The liberation of Burma, in which we have had the active assistance of the Burmese, marks not only the successful accomplishment of the first stage of your advance. It will also be your springboard for further and greater victories”.

Less than three months later, on August 6, an atomic bomb nicknamed ‘Little Boy’ was dropped over Hiroshima. Some 80,000 civilians died immediately or shortly thereafter. Three days later, it was the turn of Nagasaki. Less than a week after that came the unconditional surrender of Japan. The war, finally, was over.

* Sources: George MacDonald Fraser, Quartered Safe Out Here; Max Hastings, All Hell Let Loose: The World at War 1939-1945; World War II: The Definitive Visual Guide: From Blitzkrieg to Hiroshima (Dorling Kindersley); The Chronicle of War (Imperial War Museum); Eric Yarrow, A Few Memories; https://www.burmastar.org.uk/burma-campaign/; http://www.chindits.info/

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel