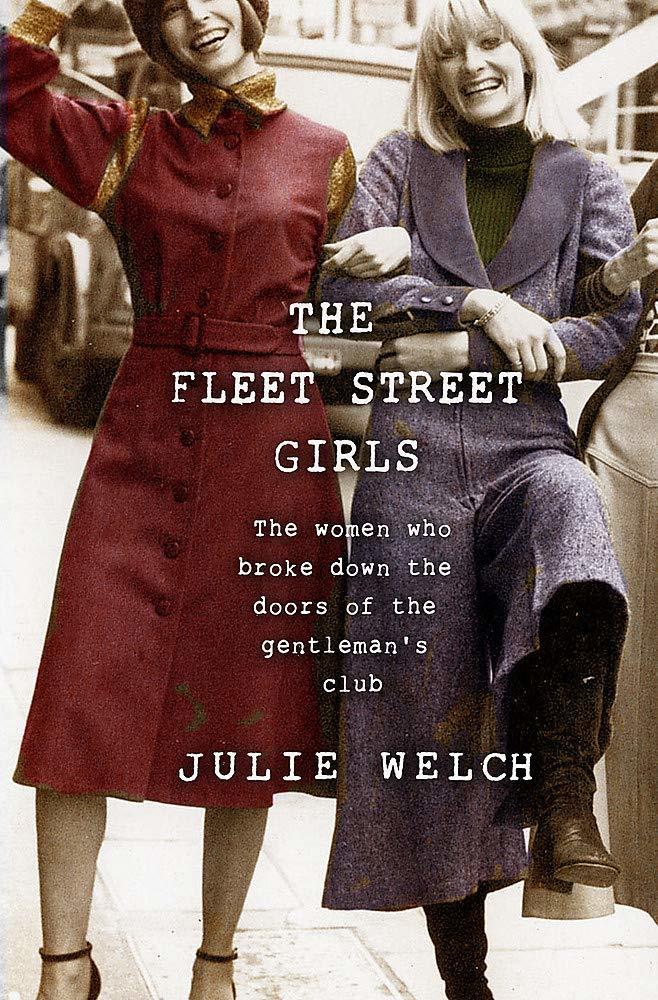

The Fleet Street Girls

Julie Welch

Trapeze, £18.99

Review by Susan Flockhart

When Fleet Street’s last two working journalists packed up and left four years ago, they were widely reported to be turning off the lights of a British institution. In truth, the famous thoroughfare had been leaching newspapers since the 1980s but when Julie Welch landed a job there in 1973, the presses were rolling at full tilt.

Her entertaining new book describes the media epicentre’s heyday, from the perspective of those who’d gained access to its hallowed newsrooms through talent and sheer hard graft – yet couldn’t even buy a drink in its most famous pub.

Fleet Street Girls tells the story of “the women who broke down the doors of the gentlemen’s club” – not least, by winning a landmark discrimination case against the legendary El Vino’s refusal to serve women at the bar.

As the first woman in Fleet Street to report on a football match, Welch was one of the conquistadors and the book combines her own recollections with those of journalistic luminaries such as Lynn Barber and Katharine Whitehorn. The result is a colourful evocation of the pre-digital and decidedly pre-MeToo culture that prevailed half-a-century ago, in fetid newsrooms where senior editors snoozed off liquid lunches amid clattering typewriters and rumbling subterranean presses.

Welch’s largely anecdotal account is light on statistics, but it’s clear that for most of its history Fleet Street was a male preserve. Well, almost. In the late 19th century, Rachel Beer became the UK’s first female newspaper editor when she took over the reins of The Observer and later the Sunday Times. (Her family owned both papers.) Assertive and fiercely intelligent, she was “a woman with real power” and therefore, writes Welch “anathema to the staff” and to distinguished contributors such as George Bernard Shaw, who became “spittle-flecked with rage” when Beer made changes to his copy.

She also engineered one of the greatest scoops in Fleet Street history, exposing the miscarriage of justice by which Jewish captain Alfred Dreyfus had been falsely imprisoned for treason.

It’s not known whether Beer employed any women. There must have been some around because in 1898, female hacks were being caricatured as sloppy, unreliable and deadline-shy in Arnold Bennett’s book, Journalism For Women. In a subsequent guide published three decades later, the author enthused about the “enormous scope” for female journalists, listing housework, fashion and “beauty culture” among the dazzling array of suitable topics.

By the 1960s, when the teenaged Julie Welch set her sights on a Fleet Street career, journalism remained male-dominated apart from a few dedicated “women’s pages”. Lacking recourse to the copy boy apprenticeships that launched many male careers, Welch went to secretarial college to gain the typing and shorthand skills she hoped would get her a foothold.

Astonishingly, to anyone familiar with today’s sparsely-resourced newspaper offices, the Daily Express’s history correspondent was advertising for a secretary. Although Welch didn’t get that job, her next application – for a clerical vacancy on the Observer sports desk – was successful. “Apparently there had only been one other applicant. She had a huge bust, so all the men said ‘Hire that one’.”

Thankfully, sports editor Clifford Makins was more impressed by Welch’s track record. Having won the Daily Telegraph’s Young Writer of the Year award as a student, she’d been interviewed by Makins’s old crony, Kingsley Amis. Nepotism was career currency on Fleet Street and mentioning the Lucky Jim author proved to be Welch’s lucky break.

But name-dropping only gets you so far. Welch was an exceptional writer whose Telegraph prize – a job on the paper – had been scuppered by an unplanned pregnancy. Now that she’d finally arrived in the “wonderful, human-sized board game” that was Fleet Street, she used her talent and ingenuity to squeeze through the chinks in the bastion’s armoury.

When she wasn’t phoning round pubs looking for writers who’d missed their deadlines or fielding calls from her boss’s many lovers, she was clocking up the occasional feature byline, eventually talking her editor into letting her cover a football match.

“Women in the press box. So it’s come to that,” muttered one of the assembled sports hacks, as she sat nervously waiting for the Coventry City v Tottenham Hotspur match to begin. “That was very good,” said another, more kindly, after the whole pack had sat listening while she phoned over her report to the Observer’s copy-takers.

Ah, copy-takers! Fleet Street Girls is full of gorgeous details about the newsroom paraphernalia of old. The overflowing ashtrays and huge typewriters on which copy was bashed out in carbon triplicate before being stuffed into tubes and sent to the machine room via overhead wires. The vicious metal spike on which unwanted copy was “stabbed to death”. The libraries full of reference books and helpful staff.

Innuendo and groping were perennial hazards. “You could almost smell the testosterone”, recalls Wendy Holden of her time at the Evening Standard. Sly suspicions drifted around any woman who achieved editorial status. Welch had won awards for her sports writing but when a football version of Private Eye was launched, she was horrified to discover a comic strip titled Miss Julie. “There I was, caricatured, some of my most pretentious phrases lampooned, along with the implication that I slept with footballers. It was libellous, but I didn’t have the guts to call them out.”

Not all Fleet Street men were dinosaurs. The huge circulations of magazines like Honey and Cosmopolitan led many editors to try to “feminise” their papers and “clear out the cobwebby old men”. Meanwhile, Welch was grateful to the Observer’s Kilmarnock-born chief sports writer Hugh McIlvanney, who’d remind colleagues sore at being upstaged by a woman that “the Lady can write most of us under the table”.

Welch clearly enjoyed being introduced by a radio DJ as “the prettiest football reporter” and writes fondly of an era when “a young woman could charm her way out of speeding tickets”. Nor were women alone in being disadvantaged. The prevailing Old Boy culture would have defeated most humbly-born males, and many of Welch’s interviewees were privately-schooled and well-connected. “Awful,” says Katharine Whitehorn of an early job on Woman’s Own. “I had to interview girls in factories.”

For all the pressure to be “twice as good as our male peers”, Welch writes gleefully of the Fleet Street Girls’ determination to “go anywhere the men did, report anything … so that we too could make decisions about what went into our papers”.

And despite the groping, sexism and exhausting pace of work, it was, she suggests, a golden era. “Love, fame, laughter, money, excitement were all there for the taking and we knew that once we left Fleet Street nothing would ever be so naughty, thrilling, so ground-breaking again.”

As newsrooms empty and more and more journalists toil remotely at laptops for ever-diminishing returns, it’s hard to disagree.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here