IN 1962, Cassius Clay and his teenage brother Rudy drove north to Detroit for a Nation of Islam rally in the Motor City. They did not travel with the full blessing of their parents. Their mother sang in the choir of her gospel church and could not imagine a road that led away from Christianity and their father, more relaxed about religion, had imagined a future where his sons would follow in his footsteps. He was a sign writer and when not painting murals and scoping out shop signs, he was drinking in the R&B clubs of Louisville, Kentucky. Both parents sensed they were losing control of their sons and that the magnetic power of a rally in the north would prove too powerful.

When they arrived in Detroit, the Clay brothers found a city bristling with excitement, tense with racial difference and on the cusp of reinventing black music. Cassius Clay was a compulsive record collector and already owned several Motown records, even although the “sound” that would make it famous was still in its infancy. One song in particular had come pounding on to his radar – Mary Wells’s boxing-themed love song You Beat Me to the Punch, written by Smokey Robinson, which reached No1 on the R&B charts later in 1962.

As Motown looked to the mainstream, Clay was slowly but surely heading in a different direction, embracing Islam, which thrived in the prisons and ghettos but had never occupied centre stage in African American society. Unlike the creed of Dr Martin Luther King it did not believe in non-violence and would not turn its cheek in the face of racial discrimination.

Casually at first, and then with growing devoutness, Clay read the Nation of Islam’s newspaper, Muhammad Speaks, and on Sunday evenings when he had finished training at the 5th Street Gym in Miami, where he was now based, he would lie on his motel bed listening to Miami's Radio Station WMIE, which carried a syndicated sermon by the Nation’s leader Elijah Muhammad.

The Olympia, on Detroit’s Grand River Avenue, was busy with anticipation. Muslims had come from across America, bussed in from Chicago and New York. The rally had been convened to protest the shooting of two Nation of Islam members by Los Angeles Police officers. Scores of policemen had ransacked the Los Angeles mosque, wounding seven unarmed Muslims, and leaving William Rogers paralysed and Ronald Stokes dead. More than 3,500 supporters of the Nation had come to register their support for the dead men. The Olympia was a beast of a building, robust and reverential, stylish and steadfast. The stadium's former general manager Lincoln Cavalieri, once said "... if an atom bomb landed in Detroit, I'd want to be in the Olympia."

Police patrols circled the neighbourhood and a hidden battalion of armed officers were out of sight in a local warehouse, on red alert. Young men in sharp suits lined the sidewalk, cordoning the entrance and body-searching the faithful. More people were crowded nearby around the entrance to a diner called The Shabazz which carried a Nation of Islam motto on its fascia: 'Every man is a builder of a temple – his body'.

It was inside The Shabazz luncheonette that the charismatic Malcolm X first forged a friendship with Clay. It was the introduction to a relationship that impacted on both their lives. Initially, their friendship was one of mentor and student. "Malcolm was very intelligent, with a good sense of humour, a wise man”, Clay once said. "When he talked, he held me spellbound for hours." As the circumstances around them changed, it became a relationship fraught with complexities, ticking down to tragedy.

Malcolm X was no stranger to tragedy. His father Earl Little had died in 1931 in the morbid darkness of Lansing, Michigan, when he missed his footing trying to board a trolley-car in the dark of night. He died in the street and unsubstantiated rumours spread that he was murdered by Michigan racist group The Black Legion.

By 1943 Malcolm was living in Harlem as a pimp and small-time crook known on the street as Detroit Red, a reference to his reddish conk haircut. After a spate of robberies, he was arrested and sentenced to an 8-10-year stretch in Charlestown State Prison in Massachusetts. It was in prison that he converted to the faith, the personification of Islam’s magical power to transform the lives of the most difficult youth.

Malcolm X raged against the legacy of slavery. "You're nothing but an ex-slave. You don't like to be told that," he once said. "But what else are you? You are ex-slaves. You didn't come here on the Mayflower. You came here on a slave ship. In chains, like a horse, or a cow, or a chicken. And you were brought here by the people who came here on the Mayflower." It was a message with which Clay struggled. To be accepted into the Nation, new recruits were required to eliminate their surname or 'slave name', effectively crossing it out with a denunciatory X.

A deepening interest in Islam was a substantial risk to Clay’s career in the notoriously conservative world of boxing, but his conversion gave him a distinctiveness too. His corner man, Gene Kilroy, who first met him at Rome Olympics in 1958, said “If he hadn’t accepted the Nation of Islam, he would have been just another fighter. It gave him a cause about life. It gave him a way to live. It made him a teacher."

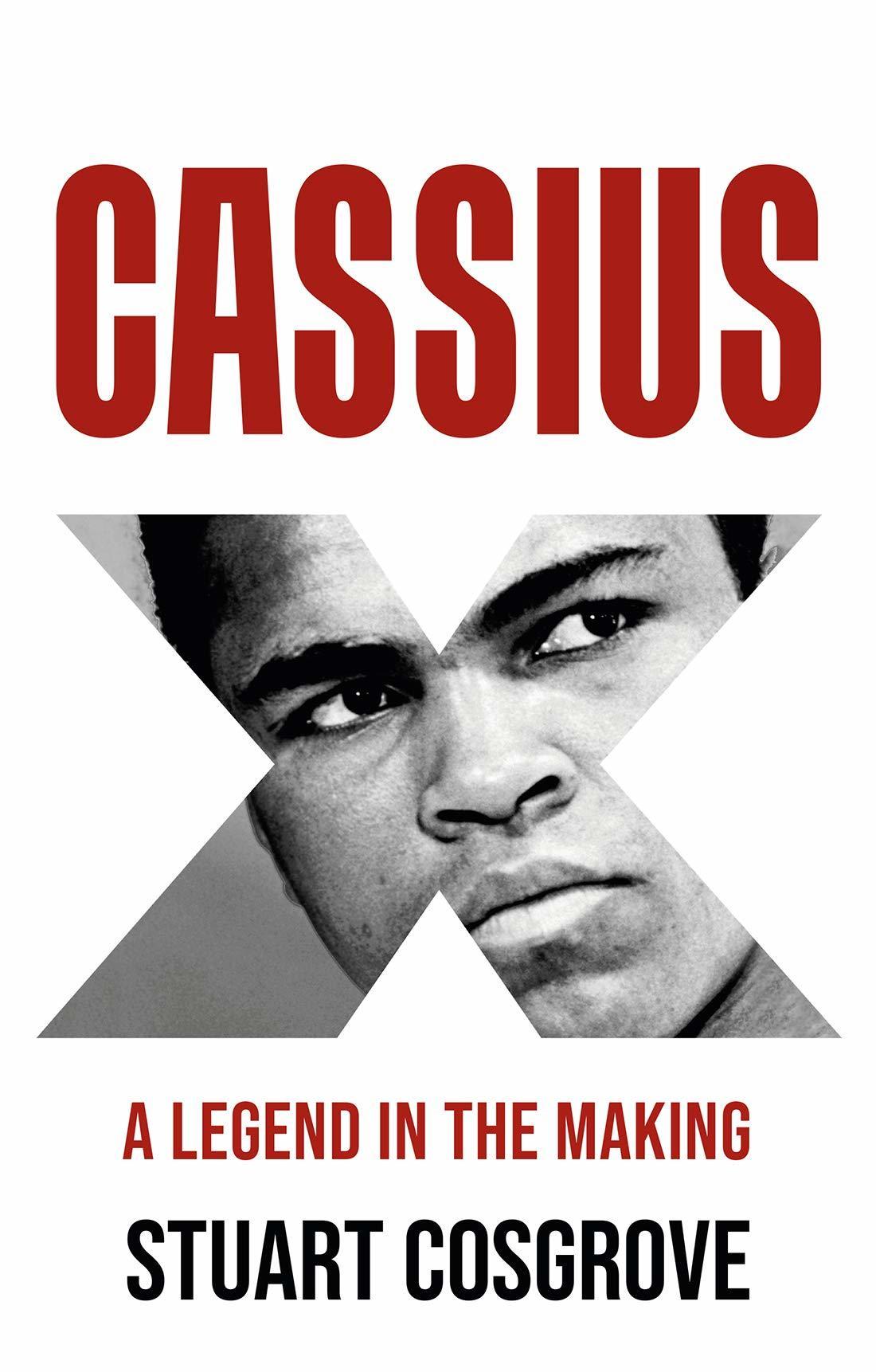

On the journey back from the Detroit rally, Clay began to wrestle a troubling dilemma. He faced up to the agonising prospect of eliminating his slave name. He had inherited the name from the Louisville plantation owner Cassius Marcellus Clay, a pioneering abolitionist who had freed his own slaves and led militia armies fighting for abolition. It was a name that he and his family had always valued and with such an illustrious and anti-abolitionist “forefather”, the boxer had grown up proud of his inherited name. Eliminating it with the letter X was a struggle but the closer he moved to the Nation of Islam, the more he fell under Malcolm X’s influence and the easier the path to full conversion seemed.

There was no ceremony and no moment of record but by the time 1963 arrived the young boxer was known privately and within the Miami mosque as Cassius X. Within a year that moment would pass too, and he would be known globally by his triumphant given name – Muhammad Ali.

Cassius X: A Legend in the Making by Stuart Cosgrove is out now on Polygon, priced £17.99.

The Soul Link

Cassius Clay was one of the great witnesses to the emergence of soul music as it emerged from the drink-sodden juke joints of rhythm and blues and the celestial choirs of the gospel congregation. Soul was a convergence of the lord and late-night entertainment, popular music that had evolved from the church.

Soul music became globally synonymous with the Motown sound of Detroit and the guttsier sound of Stax Records in Memphis. One specific track parallels the raucous journey of popular black music from the 1950s, the hurtling instrumental Night Train, a song which terrified Cassius X because it was the fearful signature tune of his nemesis, the reigning heavyweight champion, Charles ‘Sonny’ Liston.

Liston first heard Night Train on a transistor radio while brooding in his jail cell in the Missouri State Penitentiary. The song had been recorded locally in St Louis in 1951 by the tenor saxophonist Jimmy Forrest and its chugging, up-tempo pace gave it a sound like a train hurtling through the cities of the deep south. Sonny Liston took it as his own, using it as a motivator and to accentuate his raw strength and power. It became the relentless soundtrack to his training routines and when it was re-recorded in 1962 by the Godfather of Soul, James Brown, in a funkier style, the intimidating Liston had two versions to use in training.

Many claimed that in the psychological battle for the heavyweight title Night Train spooked the young Cassius X. The song sent shivers through his body and foreshadowed what the majority believed would be certain defeat. It is not quite how it worked out. The young challenger controversially took the title and a major step to becoming the most famous sportsman ever.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here