For some Americans it's not a hot election issue, but future US foreign policy could prove the most consequential of recent times for the rest of the world, says Foreign Editor David Pratt in the second of three special reports before the November 3 vote

“America First.” Remember that mantra? It was back in 2016 in the wake of his election to the White House that President Donald Trump vowed that he was going to “shake the rust off America’s foreign policy”.

Four years on, as Trump makes his bid for re-election, the country’s foreign policy stance and direction has been far from the biggest election issue.

Beset by domestic troubles from coronavirus to racial divisions and a political polarisation of US society rarely seen in recent times, foreign policy has barely been mentioned. Most Americans, it seems, have other things on their minds.

That much was reflected in last Thursday night’s final election debate between Trump and Democratic Party rival Joe Biden. There were, of course, some references to overseas concerns. But these had more to do with personal point scoring and allegations of cosy business pursuits in Moscow, Kiev or Beijing, and having “secret” China bank accounts, than America’s stance on global issues.

For once, Trump’s loudest foreign policy pitch wasn’t about his “fantastic” record, but in casting Biden as corrupt because of his son Hunter’s business associations in Ukraine.

While foreign policy might not have much play within the American electorate, for the rest of the world the outcome of the vote on November 3 will arguably be the most consequential in history.

It will, in effect, determine whether isolationism or global re-engagement is the path America chooses to take. Only the most blinkered could fail to see the significance and wide-ranging ramifications of this.

The measure of just how important foreign policy remains can be gauged by how, even at this last minute before the election, the Trump administration continues to pull out all the stops to clinch points on the issue.

There is historical precedent here such as in 1980 when then-president Jimmy Carter’s administration, beset with difficulties in his re-election bid, manoeuvred to try to secure the release of Americans held hostage in Iran. In the event the Americans were not released and Carter lost in a landslide to Ronald Reagan.

Similarly, back in October 1972, in the run-up to the presidential election, Richard Nixon’s national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, declared that “peace is at hand” in Vietnam. That, too, proved to be an election gambit that failed.

With just over a week to the ballot, can we expect Trump to try to turn his bad polling figures around with a similar 11th-hour play?

If reports are anything go by then the answer is yes. According to US broadcaster NBC last week, team Trump is already engaged in rounds of “high-stakes” diplomacy to win foreign policy plaudits from the American electorate.

Among these are efforts to salvage an arms control deal with Russia and persuading more Arab states to join the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in normalising relations with Israel under the Abraham Accords, as it’s known.

Trump’s team is also working to secure the release of Americans detained in Syria and pull more US troops out of Iraq and Afghanistan.

“The peculiar timing, combined with the hard push for immediate action, strongly suggests that these initiatives are disproportionately driven by the US electoral calendar rather than our national security interests,” William Wechsler of the Atlantic Council think tank told NBC last week.

Earlier, the broadcaster also reported that Trump is considering a sweeping foreign policy speech before the November 3 election and has been leaning on members of his national security team to accelerate these specific initiatives that he could highlight in his remarks.

“At this point in the election cycle, what you typically see is a president reminding the public of all the successes he’s had over the years,” Wechsler also told NBC.

“What you don’t typically see is a president trying to have new successes because his track record is seen as lacking,” added Wechsler, who by his own admission also regards the so-called Abraham Accords as “a real foreign policy accomplishment any way that you cut it”,

Others point to what they see as plus points on Trump’s foreign policy approach to date. Writing in last week’s Financial Times, the newspaper’s US national editor and columnist Edward Luce noted that the highest number of checks on Trump’s “promises kept” sheet are on foreign policy.

In making their case Luce and others point to the fact that Trump has “not started any new wars”. His administration has drawn down US troops from Afghanistan and the Middle East, and ensured the leader of the Islamic State (IS) group was killed and the extremists’ territorial hold eroded.

Likewise, those counting the positives among Trump’s foreign policy moves acknowledge his calling out of China as the chief threat to the US in global power rivalry and his forcing of America’s allies to think again about who financially underwrites their security.

As Luce added in his Financial Times op-ed last week, while “you may disagree with any or all of the above ... it would be hard to argue that Trump was trading in idle promises during the 2016 campaign”.

Many other observers, of course, totally dispute such an assessment, insisting instead that Trump’s term in office has been characterised by confrontation, the alienating of allies, and the trashing of America’s global reputation.

Trump’s cosying up to North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, they insist, was nothing but grandstanding, a desire for photo opportunities with authoritarian strongmen and power envy by a US president near obsessed by such things.

Those critical of Trump’s foreign policy also point out that US withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal only goaded Tehran and meant it has more highly enriched uranium available for a nuclear weapon, more operating nuclear facilities, and more sophisticated technology now than ever before.

In Afghanistan, meanwhile, US troop drawdown has left the people of that country at the mercy of a resurgent Taliban despite ongoing peace talks.

Then there is what many see as Trump’s dodgy deals with certain Gulf states which, they attest, are driven by profit, not diplomacy. His highly contentious moving of the US embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, meanwhile, has also driven a horse and carriage through the quest for Middle East peace.

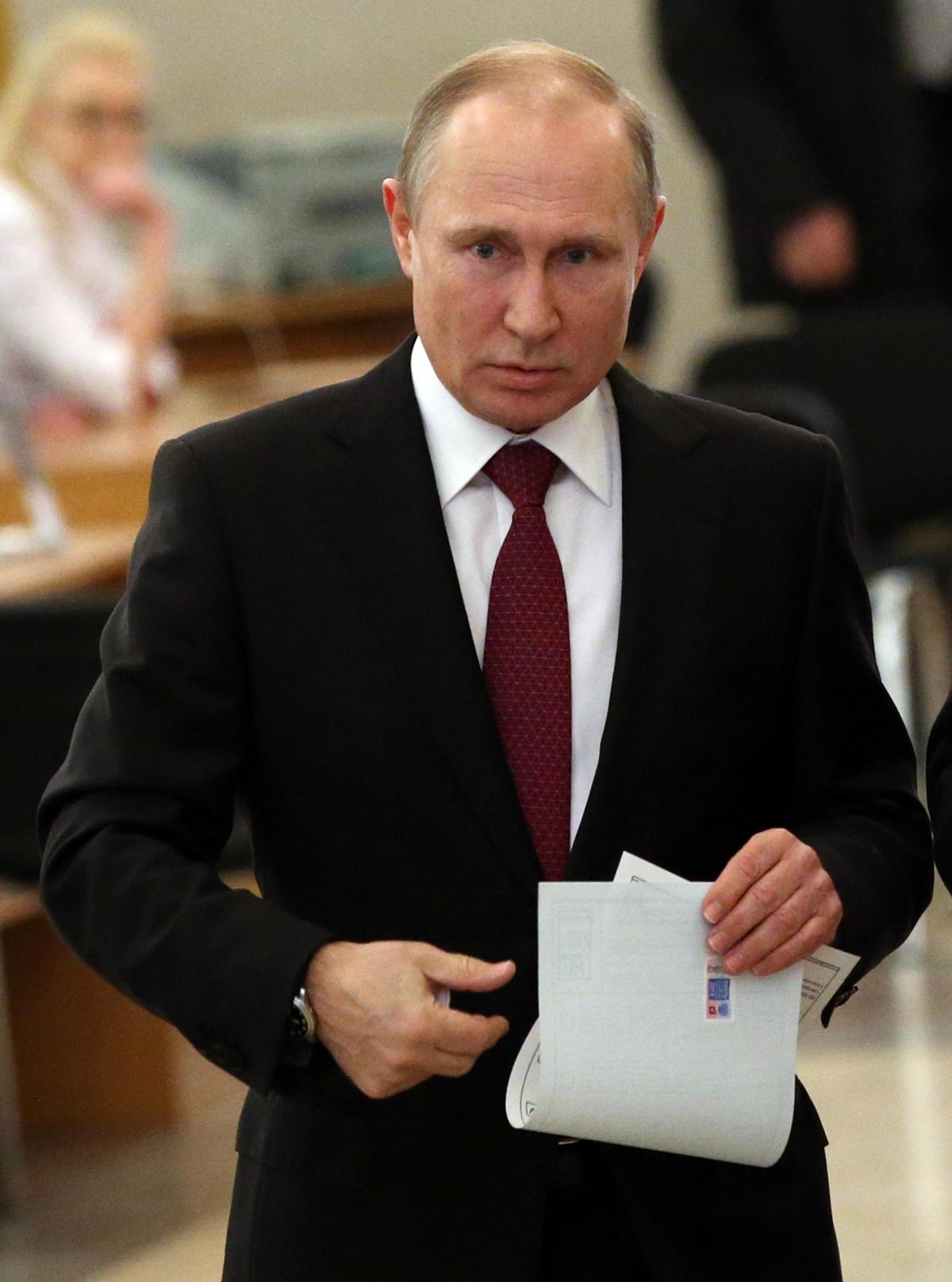

Last but far from least there is the thorny and nagging question of Trump’s personal relations with Russian president Vladimir Putin. Just what is going on there?

As for relations with China, critics say Trump has done little more that anger Chinese president Xi Jinping rather than strive for any real co-operation with Beijing or take necessary steps to counter the likes of unfair trade practices or control over the South China Sea.

“What remains after all these failures is a clear effort by Trump and his allies to obtain Russian and Chinese help for his re-election,” concluded Professor Wendy R Sherman, director of the Centre for Public Leadership at Harvard Kennedy School, writing in the influential Foreign Policy magazine earlier this year.

In an article entitled “The Total Destruction of US Foreign Policy Under Trump”, Sherman called on readers to remember the Republican presidential candidate’s plea for Russia to interfere in the US election when running in 2016.

“This time around, we know from former national security adviser John Bolton that Trump, at the June 2019 G-20 summit in Japan, pleaded with Xi to help him win re-election,” added Sherman, referring to revelations in Bolton’s controversial memoir The Room Where It Happened.

Given these very differing assessments of Trump’s foreign policy track record, how then might we see its impact play out over the next week in the battle for the White House? How does it compare with what Democrat rival Joe Biden can offer or might do should he become president?

While it might not resonate with Americans as much as some domestic issues, voters still face a stark difference between the Republican and Democratic nominees, their views of the world and the United States’ place in it.

Then there is the inescapable fact that the most pressing domestic issue facing America is, in fact, one that has been described as the “first big national security challenge”. One that would require Biden to make good on his promise of better co-ordination between the US and its allies. That challenge, of course, is the coronavirus pandemic.

On this, the most important of global threats, few would defend Trump’s record, recognising that whatever the election’s outcome it will still be the most pressing international issue bearing down on America needing addressed.

“The 800-pound gorilla that will still be making its presence felt on January 21 (inauguration day) is still going to be Covid-19,” said Tony Blinken, Biden’s top foreign policy adviser, speaking to the Associated Press agency last week. “The world doesn’t stop just because we have this Covid crisis ... We would have to walk and chew a lot of gum at the same time,” he added.

For Biden’s campaign the message is clear. As president he would seek to reset four years of isolationist US foreign policy under a new tagline – “restoring American leadership” – rather than “America First” in an attempt to repair strained diplomatic relations. Co-ordination and co-operation with allies over tackling the pandemic is one way of doing that. As Biden himself said in a town hall speech last week, “America First has made America Alone”.

Once the chair of the Senate Foreign Relations committee, Biden harks from a different time and place to Trump. A time of the bipartisan establishment that shaped US international policy after the Second World War until Trump’s election. If elected as US leader he would not hesitate to reverse Trump’s signature foreign policy decisions. Among these would be immediately re-entering the Paris climate accord and halting the country’s exit from the World Health Organisation (WHO). The former

vice-president has also signalled that he will rejoin the Iran nuclear deal if Tehran comes back into compliance, boost diplomatic support for Nato, and think again on relations with Saudi Arabia.

“Biden will have a lot of repair work to do,” Brian McKeon, another of Biden’s foreign policy advisers, told the Financial Times last week.

“Trump has attacked all our allies and partners, embraced dictators, launched trade wars that haven’t worked very well for the middle class, and walked away from global institutions,” McKeon added. While the polls still look in his favour, Biden, however, is not yet president and Trump can be sure to fight to finish trying to secure foreign policy wins in doing that.

To that end, Moscow appears to be offering a helping hand in the shape of supporting a Trump administration proposal to freeze nuclear warheads for a year and extend the last major nuclear arms control treaty between the two powers, known as New START.

Should that agreement be concluded it’s a fair assumption American voters and the world will hear about it soon enough as will they hear of any further troop drawdowns from Afghanistan or Iraq that would bring American “boys and girls” home for Christmas.

For now, we can only wait and see if Trump follows through on reports that he will make a sweeping foreign policy speech before the election.

If the latest polls are anything to go by – even if rising slightly in his favour – Trump needs all the help he can get. Most likely he will make that speech even if what he might say is anyone’s guess. Back in 2016, “America First” tapped into the US voter mindset in a changing world order. But today that world has dramatically changed. Biden versus Trump is probably the starkest choice between two different foreign policy visions of any American election in recent times.

For those voters who will determine the election’s outcome, many of whom have already cast their ballots, polls still show that foreign policy ranks among the least important of issues.

For the rest of the world, however, it’s an altogether different story and enemies and allies alike of the US will be watching closely to see if Biden comes through or Trump consolidates his isolationist vision.

“Our friends know that Joe Biden knows who they are. So do our adversaries,” insisted Biden’s foreign policy adviser Tony Blinken last week. “That difference would be felt on day one,” he predicted. It may very well be felt on day one. But for now the most important day on everyone’s mind still remains November 3.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel