Just how can Donald Trump be winkled out of the White House which, in the last few days, has more resembled the Alamo, with a doomed band of zealots fighting impossible odds down to the last surviving writ?

The president has cited John Wayne, who starred in the movie version of the siege, as a particular hero of his and leapt to his posthumous defence when the pesky Democrats wanted to rename the airport in Orange County, which carries Duke’s moniker, after an old interview surfaced which had the actor confessing to being a white supremacist.

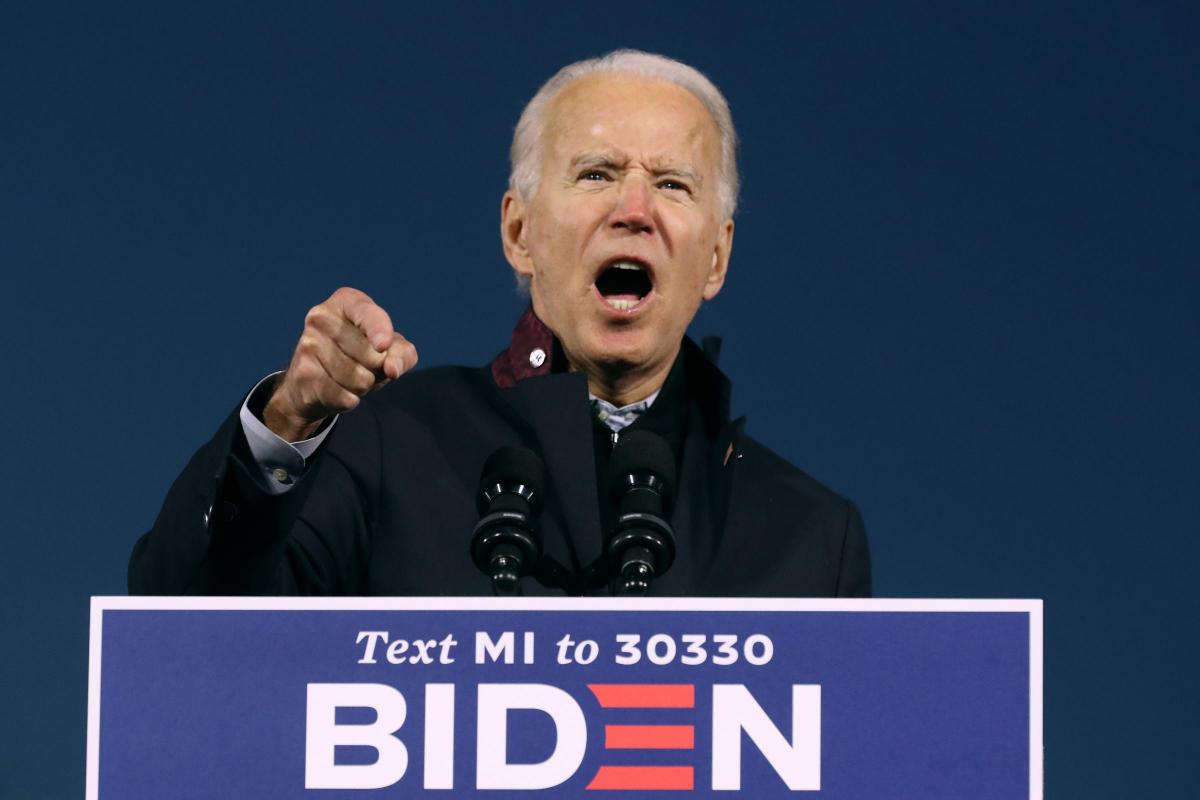

Political life is altogether riskier than the celluloid version, of course, and Trump seems determined to hang on in the Oval Office until the Marines come in and drag him out. Emily Murphy, his appointment as head of the White House General Services Administration, is refusing to allow Joe Biden’s transition team access, until the result is officially ratified.

That could take until December 14 – traditionally the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December – which is the day the 50 states’ electoral colleges meet to cast their votes for president and vice-president. So all the legal challenges swirled around must be completed by then.

But we are in unknown territory with a mercurial president whose actions, and those of his closest allies, are difficult to predict. Could one or more electoral colleges refuse to ratify the clear winner? Unlikely. On January 6 next year, just 14 days before the new president takes office, Congress convenes to formally count the electoral votes and certify the winner. As vice-president, Mike Pence is also president of the Senate and he presides over the count.

Could he refuse to ratify? Again unlikely, but what is looking like a racing certainty is that when Pence asks if there are any objections to the result there will be one or more hands up. It happened in 2001 when Democrats tried for 20 minutes to block Florida’s college votes for George W Bush, after the issue of the “hanging chads”, the contested punch holes in ballots, went all the way to the Supreme Court (which, of course, is now stacked 6-3 in Trump’s favour).

One of the reasons that Trump is refusing to concede, apart from his pompous vanity, may be the fear of criminal proceedings when he leaves office. One rumour is that he will resign from office before January – Pence will then be sworn in briefly as interim president and pardon Trump. Or even that Trump could pardon himself.

That’s not too outlandish and no conspiracy theory. In 1974, the disgraced president Richard Nixon considered it. Following the release of the “smoking gun” tape in August implicating him in the Watergate burglary cover-up, his position was untenable and he talked to his close circle about whether he could do that.

What happened was his chief of staff, former general Alexander Haig, approached Gerald Ford, who would become president, and mooted the idea of a pardon. Nixon resigned in August and after Ford took over, with almost his first act, issued Nixon a full and unconditional pardon “for any crimes that he might have committed against the United States as president”.

Joe Biden might not bite on that because, after that pardon, Ford’s popularity slumped and he lost the 1976 election.

What is much more likely is that Trump will try to poison the political well for Biden, as presidents have done in the past. George Bush Senior may have left a welcoming note on the desk in the Oval Office for Bill Clinton, but he embroiled the new Democrat president in a bloody and fruitless military escapade.

In December 1992, just weeks before Clinton was sworn in, Bush sent 30,000 US troops to Somalia on what was claimed to be an open-ended humanitarian mission and which turned out to be a humiliating catastrophe. In October 1993, in what later became known as the Battle of Mogadishu, 18 US soldiers were killed. Images of their dead bodies being dragged through the streets were broadcast on television stations all over the world, horrifying the American public, turning support against involvement.

Four days later, on October 7, sensing the public mood, in a nationwide television address Clinton effectively ended the US mission in Somalia and set a date in March 1994 for troop withdrawal. They exited three weeks earlier than planned.

Trump is one of the few recent presidents not to send US troops to war, but he has taken military action and if he is tempted to then Iran is top of the target list. In January, he ordered a cruise missile strike on Iran’s most powerful military commander, General Qassem Soleimani, head of Iran’s elite Quds force. Suleimani was assassinated, along with close military aides, at Baghdad airport.

On Thursday, the United States’ closest Middle East ally, Saudi Arabia, called for a “decisive stance” against Iran. King Salman bin Abdulaziz accused Tehran of intervening in other countries, of fanning the flames of terrorism, and in a barely-coded message called for action “that guarantees a drastic handling of its efforts to obtain weapons of mass destruction and develop its ballistic missiles programme”. Trump will have heard it loud and clear.

In September, and then last month, Trump imposed sweeping new sanctions, including further ones against Iranian banks. Missile strikes against nuclear laboratories and sites would be a further ratcheting up, but it would have the backing of not just Saudi Arabia but Israel, and would play well at home as a bloody valediction.

Biden has signalled a willingness to revive the Iran nuclear deal which Trump walked out on two years ago, but after four years of repeated warnings about the alleged threat, and without control of the Senate, he may find it all but impossible politically to stretch out his hand. Iran would, certainly, demand the ending of sanctions and compensation, even in back-channel talks.

Naysan Rafati, senior analyst at the independent Crisis Group, said: “The Trump administration’s approach now is to add more and more threads to this spider web and hope the next guy has a hard time washing them away. There’s very little in here that’s totally irreversible.

But these are harder to undo because you have to make the case that terrorism is no longer a concern.”

The biggest bear trap for a Biden presidency lies in Georgia, the deeply religious and conservative state in the heart of the Deep South. The Republican secretary of state there has ordered a hand recount of the ballot, which the former vice-president won by 14,000 votes, but it isn’t expected to alter the result. The real fight, however, is in two disputed Senate seats which the new president needs to win to control the upper house and avoid his policies being stymied.

Georgia’s arcane voting regulations, framed in the Jim Crow era, insist that a successful candidate must poll 50 per cent or more and in the two contested seats neither candidate reached the threshold. In one, a Republican had a narrow lead while in the other the Democrat was seven points ahead. The run-off is on January 5.

Historically, run-off elections in Georgia were used to suppress black votes, imposing the threshold so black voters could not unite behind one candidate and win the popular vote.

Biden must take both seats, which would bring a 50-50 tie in the Senate. However the vice-president – Kamala Harris, the first woman vice-president and the first black one – would then have the casting vote, which would be some measure of historical recompense.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel