Burns night has been and gone, but poetry is for every night, and day. It’s a source of solace, comfort and cheer in difficult times like this current pandemic and lockdown So here, to help you through, are twenty of Scotland’s greatest poets, who aren’t Robert Burns.

William Dunbar (circa 1459-1530)

“Back to Dunbar!” was a favourite phrase of Hugh MacDiarmid, and the man he was talking about was a Middle Scots poet attached to the court of James IV, who wrote works that were rhetorical and lyrical marvels. Dunbar was one of a group of medieval Scots known as the “makars” and for him the writing of poetry was "making". He created poems for his patron, such as The Thrissil and the Rois, a celebration of James IV's marriage to Margaret Tudor. But Dunbar was about more than creating snapshots of court. He created poems that have resonance now. Lament for the Makaris, with its frequent refrain, timor mortis conturbat me (fear of death troubles me), still has an extraordinary potency – even as it lists the names of makars now forgotten

Quotable lines: “I that in heill wes and gladnes,/ Am trublit now with gret seiknes,/ And feblit with infermite;/Timor mortis conturbat me." (Lament For The Makaris)

Robert Fergusson (1750-1774)

The fast-living genius who died to young, but left his mark. Robert Burns called Robert Fergusson his ‘elder brother in misfortune, by far my elder brother in the muse” when he commissioned a headstone in Canongate Churchyard, thirteen years after the poet was buried there in an unmarked grave, having died a pauper, having fallen heavily down a flight of stairs, at just 24 years of age.

We were reminded of his poem, The Daft Days, in Lidl’s recent advertising campaign which claimed to have unearthed a forgotten Scots phrase. Though, of course, anyone who knows Robert Fergusson would have known exactly what was being referred to, that strange, transporting time between Christmas and New Year.

Despite his short life, Fergusson made a significant impact and played a key role in the Scots vernacular revival, writing in both Scottish English and Scots. Many of his poems were printed from 1771 onwards in Walter Ruddiman's Weekly Magazine. Notable poems include Ode to the Gowdspink, Caller Oysters, the Daft Days, The Ghaists and Auld Reikie, a 300-line Scots work, praising Edinburgh, through description of the lives of ordinary people.

Quotable lines: “Auld Reikie wale o ilka town”, which translates as “Edinburgh: best of every town.” (Auld Reikie)

Joanna Baillie (1762-1851)

Baillie might not be a household name, but she was one of the most ambitious female writers of her time, best known for her theatrical sequence, Plays On The Passions, and also an extraordinary poet. She was born into a wealthy family in Lanarkshire, who claimed as one of its ancestors Sir William Wallace. Her father was a minister who would become Professor of Divinity at Glasgow and her mother the sister of the anatomists, William and John Hunter. But she would later move to London, where she would meet the novelist Fanny Burney, and be encouraged to write her first poem, Winter Day. Among her most relatable poems are A Mother To Her Waking Infant, which meditates on the helplessness of both the young and old, and To Cupid, a reflection on why we love those we do.

Quotable lines: “From thy poor tongue no accents come,/ Which can but rub thy toothless gum:/ Small understanding boasts thy face,/ Thy shapeless limbs nor step nor grace:/A few short words thy feats may tell,/ And yet I love thee well.” (A Mother To Her Waking Infant)

Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832)

We now know him better as the author of fiction, particularly The Waverley Novels, but actually Scott first found success as a poet, and was, for some time the best-reviewed and best-paid poet of his period. His first major publication was his three-volume collection of ballads which he had gathered and edited, The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1802–3), and this was followed by his long romantic poems The Lay of the Last Minstrel, The Lady of the Lake and Marmion, effectively a novel in verse.

Quotable lines: "Oh what a tangled web we weave, when first we practice to deceive!/ Look back, and smile on perils past./ The will to do, the soul to dare.” (Marmion: A Tale of Flodden Field)

Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894)

Though far more well known for his classic novels, Stevenson also wrote poetry, including a popular collection titled A Child’s Garden of Verses. The inspiration for this was Kate Greenaway’s best-selling, Birthday Book For Children – his response to which was, “These are rather nice rhymes and I don’t think they would be difficult to do.” In search of "some coin" he gave it a go. Perhaps most popular is his From A Railway Carriage, with its thrilling rhyming and thundering pacing.

Quotable lines: “All by myself I have to go/ With none to tell me what to do — /All alone beside the streams/ And up the mountain-sides of dreams." (The Land Of Nod)

Violet Jacob (1863-1946)

Described by Hugh MacDiarmid as “by far the most considerable of contemporary vernacular poets”, Jacob was a key voice in the revival that took place at the turn of the 20th century, centred on the North East of Scotland, and including other vernacular poets like Marion Angus. Her most famous verse, The Wild Geese, a poem of longing an desolation of exile, takes the form of a conversation between the poet and the North Wind. Jacob was haunted by the loss of her son, killed in 1916, and that grief haunts many of her poems, particularly her startling Halloween.

Quotable lines: ‘Oh tell me what was on yer road, ye roarin’ norlan’ Wind,/ As ye cam’ blawin’ frae the land that’s niver frae my mind?” (The Wild Geese)

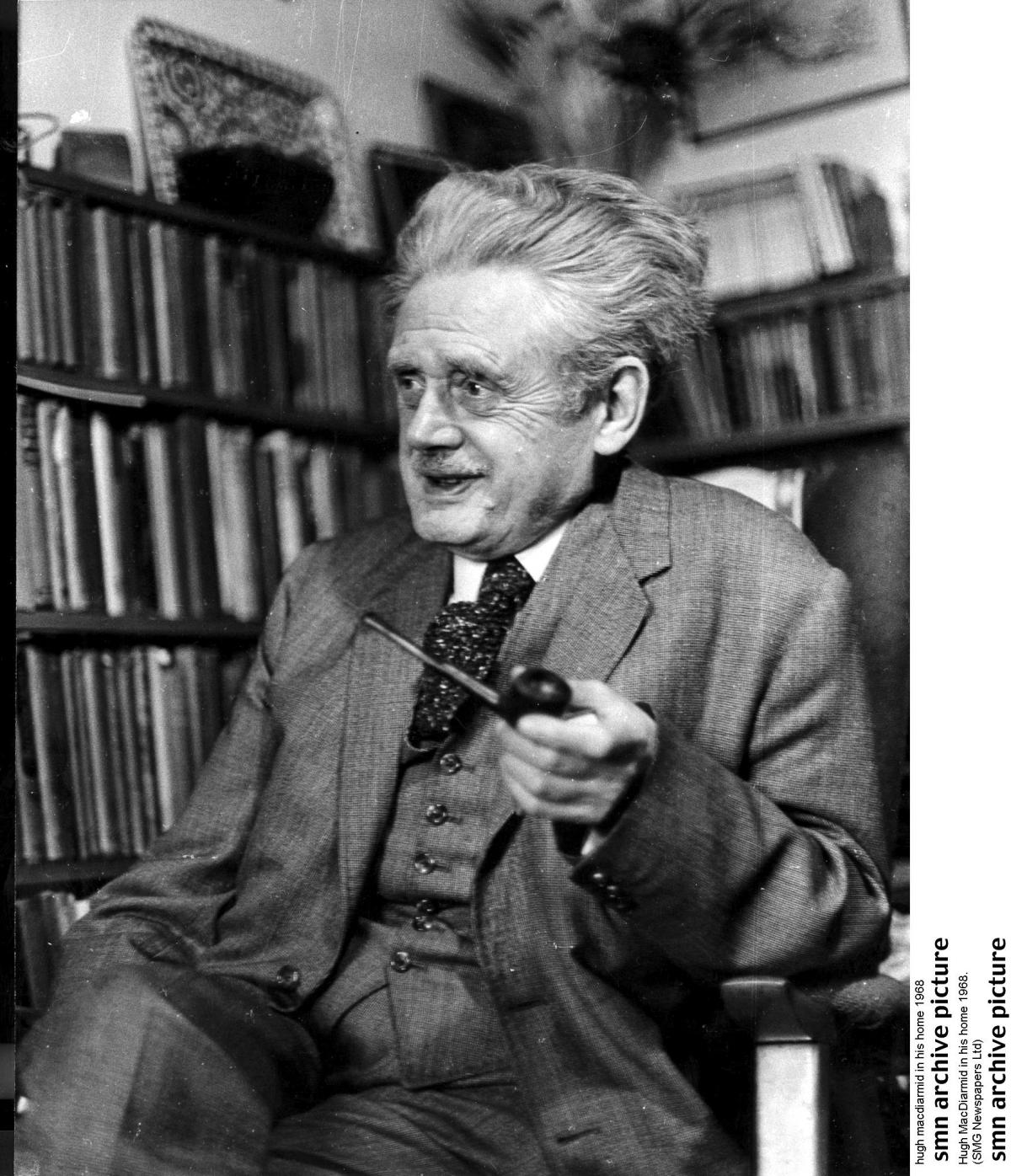

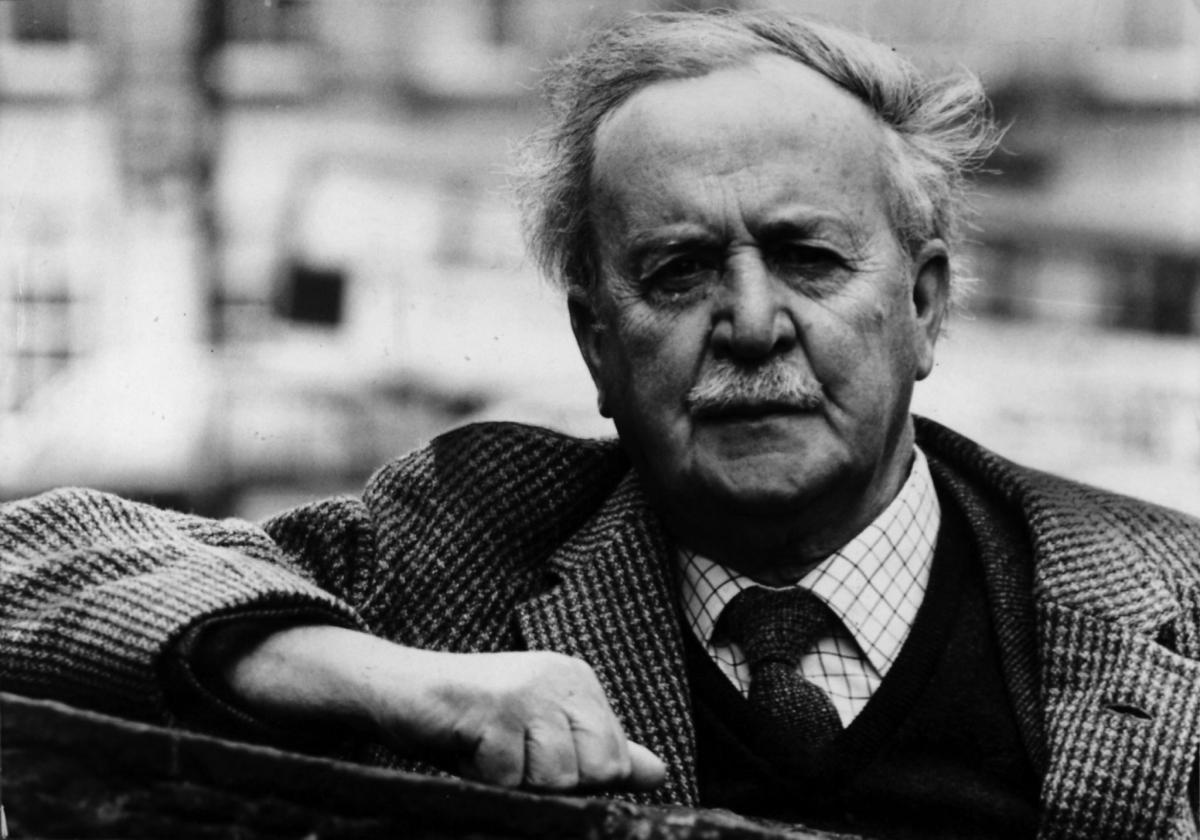

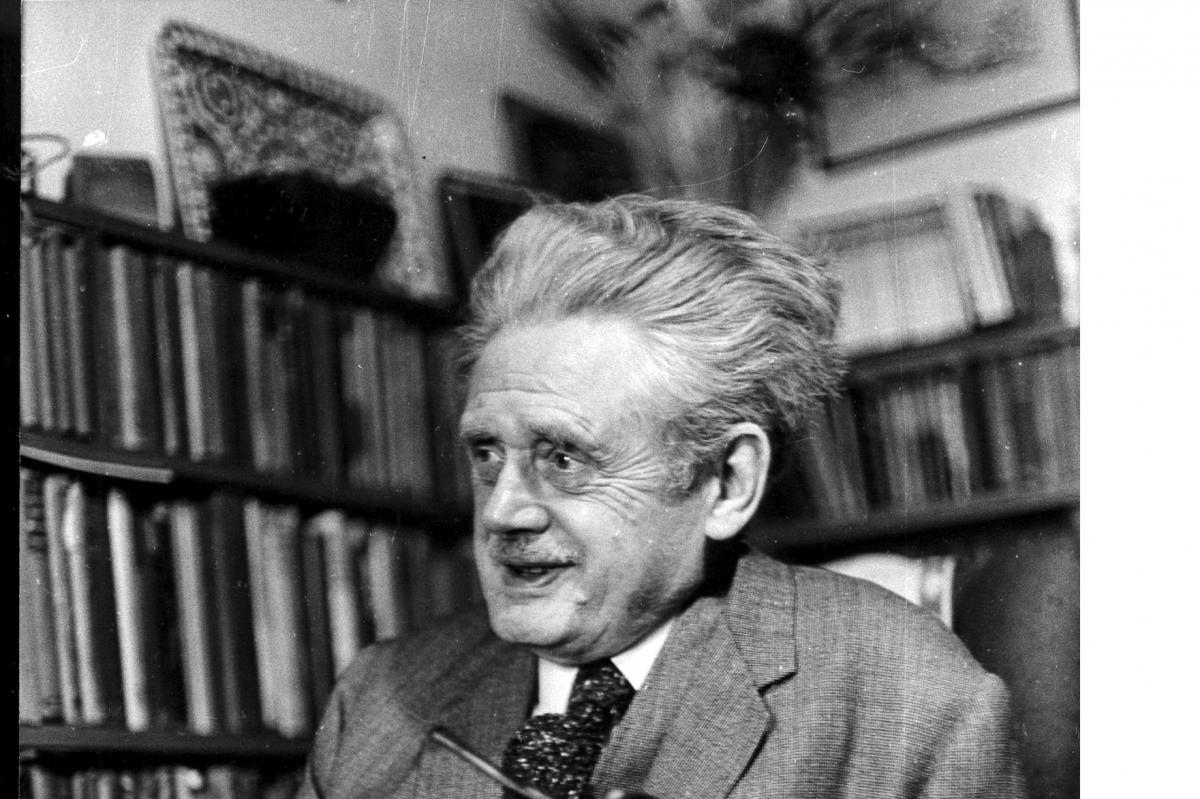

Hugh MacDiarmid (1892-1978)

A monumental figure in the Scottish literary revival and nationalism itself, it says a lot about the controversial poet and polemicist that he was kicked out of the National Party for his communism, then expelled from the CP twice for his heresies, including nationalism. In his Who’s Who entry he described his hobby as Anglophobia. Whether you delight in his opinions or not, there’s no doubting the power of MacDiarmid’s poetry. Among his most simply beautiful, and popular poems is The Watergaw, in which he sights a fragment of a rainbow, “wi’ its chitterin’ licht”.

Or there’s the Bubblyjock, a poem about a turkey, “hauf like a bird and hauf like a bogle”. And if you want a lang read you can’t do better than the epic, sprawling monologue, A Drunk Man Looks At The Thistle.

Quotable lines: “I’ll hae nae hauf-way hoose, but aye be whaur Extremes meet.” (A Drunk Man Looks At The Thistle)

Nan Shepherd (1893-1981)

Nan Shepherd’s writing has done, in recent years, an astonishing rise from relative obscurity, to cult status – and much of that meteoric rise can be attributed toher championing by the nature writer Robert Macfarlane. Hers has seemed, for many, the voice to turn to in these times of ecological crisis, her Living Mountain, not just a memoir but also now, for many, a handbook for how to connect with and experience the land. But, Shepherd wrote poetry as well as novels and memoirs, conjuring up the living world.

Quotable lines. “Living water/ Like some pure essence of being/ Invisible in itself/ Seen only by its movement.” (From The Hill Burns)

Norman MacCaig (1910-1996)

MacCaig is probably best known for his poems devoted to the “unemphatic marvels” of the natural world – toads, dogs, herons ducks, sharks, horses and birds. His poems, often humorous and accessible, but also elegiac, mostly take as their locations his home town of Edinburgh, and Assynt, where he had his holiday home. MacCaig could capture the stars: “Trees are cages for them: water holds its breath/ To balance them without smudging on its delicate meniscus.” He could summon a small loch into being with the lines, “Dandling lilies and talking sleepily/ And standing huge mountains on their watery heads.”Brian Morton once described him as, “perhaps the finest rhyming poet of the last fifty years.” Perhaps his most noteworthy work was A Man in Assynt – which said so much about human relationship to the land.

Quotable lines: “Who possesses this landscape? –/ The man who bought it or/ I who am possessed by it?” (A Man In Assynt)

Sorley Maclean (1911-1996)

Widely considered to be the greatest Gaelic poet of the twentieth century, born on the island of Rasaay and brought up immersed in the language and song, Maclean sparked a Gaelic renaissance in Scottish literature. His greatest works are widely considered to be the Dàin do Eimhir and An Cuillithionn. But it is his haunting poem of landscape left after Highland Clearances, Haillaig, that is probably most well-loved. Seamus Heaney, described how, on listening to Maclean read it in Gaelic, he felt, “This was the song of a man who had come through, a poem with all the lucidity and arbitrariness of a vision.”

Quotable lines: Tha tìm, am fiadh, an coille Hallaig/ Tha bùird is tàirnean air an uinneig/ trom faca mi an Àird Iar/ ’s tha mo ghaol aig Allt Hallaig/ ’na craoibh bheithe, ’s bha i riamh.” (“Time, the deer, is in the wood of Hallaig/ There’s a board nailed across the window/ I looked through to see the west/ And my love is a birch forever/ By Hallaig Stream, at her tryst.”)

Burns night has been and gone, but poetry is for every night, and day. It’s a source of solace, comfort and cheer in difficult times like the current pandemic and lockdown. So here, to help you through, is the first ten of our list of twenty of Scotland’s greatest poets – the rest, the poet of the earlier years, will be published tomorrow.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here