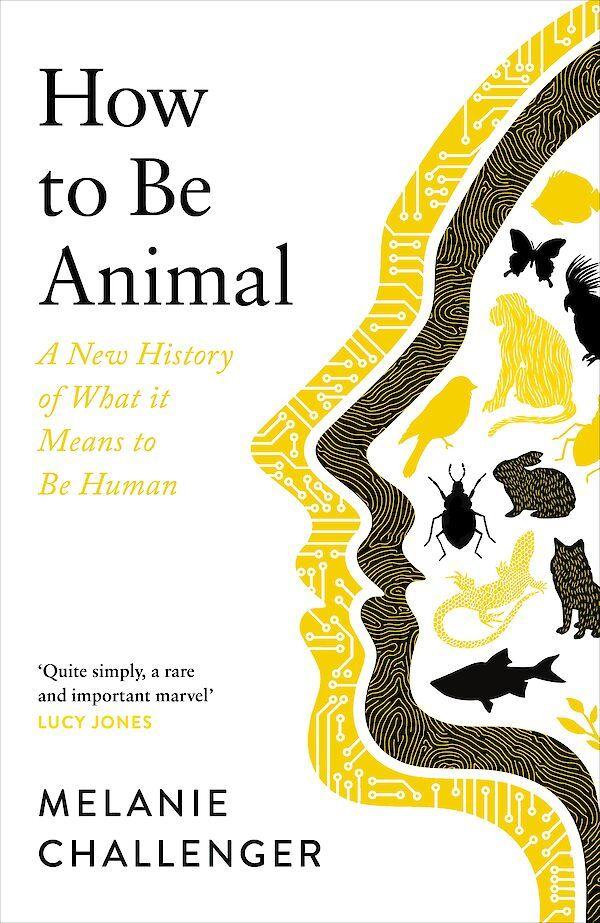

How to Be Animal: A New History of What it Means to Be Human

Melanie Challenger

Canongate, £18.99

Review by Mark Smith

I’ll start with a memory. I was about eight or nine years old. I was at Sunday school. I asked the teacher a question – do animals go to heaven? – and his answer was definitive. No, he said, animals do not go to heaven and – even now, 40 years later – I still remember how I felt about that. To me, the teacher’s answer seemed illogical and unfair, and I also remember thinking, there and then, that if animals were excluded from heaven, then religion – or this type of religion anyway – was not for me.

The reason I bring up the childhood memory now, four decades on, is because religion, and to some extent the secular beliefs that have succeeded it, still affect the way we see, and treat, animals. But it’s also because there appears to be some hope – in books like How to Be Animal by Melanie Challenger – that humans are starting to change their minds on the subject. Challenger has examined the latest research on animal, and human, behaviour and her conclusion is clear: we are not as different from animals as we think we are.

The examples she cites are striking – the orangutans who teach their young to use sticks to get at termites, for example, or the bees that experiments have shown use memory and spatial perception in the same way we do. But Challenger also makes the deeper point that in most of our fundamental activities, we behave little different from other creatures. We kill and eat animals. We expel the waste form our bodies. We seek out mates and raise offspring. And one day we die and decay to nothing.

Ah yes, but some people say humans have a unique quality that differentiates us from other animals. The priests and Sunday school teachers call it a soul – a personality that survives after death – and even some scientists assert a secular equivalent. The roboticist Hans Moravec, for example, tells us that “physical activity will gradually transform itself into a web of increasingly pure thought”, which raises the idea that, one day, we might be able to endlessly download our brains into computers, thereby achieving a kind of immortality. I’d like to see an orangutan or bee attempt that.

But Challenger’s point – which she makes with the logic of a researcher and the lyricism of a poet (she happens to be both) – is that our sense of self – or soul if you prefer – is not as distinct from our animal bodies as we think it is. Studies of the microbial influence of our guts, for instance, suggest a potential role in depression. Challenger also highlights some fascinating research on kidney transplants which shows how a new organ can disrupt the whole system of an individual, including their sense of identity and mental health. In other words, the mind and the body are intimately, and mysteriously, connected.

The point Challenger is making – and it’s a compelling one – is that most of us don’t see things that way; most of us see our sense of personhood as largely a mental experience. The problem with this approach, says Challenger, is that we can begin to see the rest of our animal experience, or physical reality, as less important or even separate to who we are, and this, in turn, can lead to another problem: a sense of separation between us and the physical reality of other animals.

How to Be Animal lays out some of the other possible consequences of looking at ourselves in that way, including our use of animals for food, or clothing, or medical experiments. Many of us can do this without guilt, suggests Challenger, because we have made a judgement that animals are different from us and don’t possess minds in the way we do; they are body but we are mind. “The pig,” she writes, “can be rendered unconscious, hung from a rail and slit behind their jowl to sever both jugular and carotid” and yet the Labrador, which is just as sentient and sensitive as a pig, sits curled up at our feet. Challenger argues the difference may come down to the judgement that a dog is more like us, and less like an animal, and therefore more worthy of protection.

Is her argument ultimately convincing? I guess that will depend on your own sense of personhood and self – some people’s minds and bodies are more connected than others. It may also depend on the influence that priests and futurologists and roboticists do, or do not, have on you. Challenger suggests most of us see the body as an elaborate walking stick for the mind and I suspect many of us will empathise with that, particularly when we’re physically ill and are, in Challenger’s words, “surprised by our frail fresh”. I also haven’t entirely abandoned the hope of my eight-year-old self in Sunday school pining for a heaven where humans can be reunited with their beloved pets.

The fact that How to Be Animal has been published in the middle of a pandemic may also underline Challenger’s point. The intellectual, technical, and scientific abilities of humans have produced a vaccine against Covid-19 and, on the face of it, that emphasises the gap between us and them – animals could never develop a vaccine just as chimpanzees given a typewriter could never produce the complete works of Shakespeare. This is a difference between us and them.

However, the virus points to our sameness too. The fact that humans can fight back against coronavirus with knowledge and science and self-awareness certainly makes us different, but not in any meaningful way. The vaccine does not change the facts of our animal lives: whatever happens next, we are still vulnerable, just like every other creature on the planet, to injury, disease and ultimately death. Humans may be a different kind of animal, but we are animals none the less.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel