THE tramp around my exercise yard in the time of Covid has been accompanied by the understandable nagging from ageing limbs but also the more incomprehensible summons to times past.

A regular companion has been Cillian Murphy. Or, at least, his voice. The actor has a show on Radio 6 that is broad in its scope and regularly powerful in its ability to spark memory. So it was, with snow suitably drifting up the slope from Maryhill, that I met again with the members of the Red Army Choir.

It was not the surprise of hearing the Song of the Volga Men on an otherwise contemporary song list that caused me to pause. It was not my aching calves (and who brings small cows on a walk in a suburban park?) It was, rather, that I had been transported back to childhood and the dimmest of memories.

Continuing the walk, my brain insistently protested that I had not only seen the Red Army Choir but in concert with Andy Stewart. This led me to believe that a period of ingesting dodgy substances in student flats off Byres Road in the 1970s had finally caught up with me. Either that or I had cooked the wrong mushrooms for my afternoon risotto.

Sanity was reclaimed on the internet. And who could ever have imagined writing that sentence. A quick search revealed that the Red Army Choir appeared with Oor Andy, Duncan Macrae and Rikki Fulton in the Empire Theatre on March 31, 1963.

READ MORE HUGH: Timeless love and the lesson of living in the present

I would have been eight years old. It was, almost certainly, my first concert, if one dismisses the regular performances in the front room of a Friday night when the eclectic sets could include granny singing Rose Marie and faither chanting Killiecrankie. But if the memories are vague, the hopping, jumping and general roaring of the choir did set me off on a march that has continued until the Covid siege.

I love a gig. Within a decade of the skirmish with the Red Army, I had become a veteran of the Glesca concert. I had learned to be careful around bouncers whose relentless aggression in another life had surely tipped the balance at Stalingrad. I had mastered the art of walking on carpets so sticky that one suspected that diving boots had been supplied at the entrance. I had accepted, too, that concert smoke not only gets in your eyes but could do strange things to your perception.

There are musical memories that survive all of this, of course. An early example is the Led Zeppelin concert (internet shows it was Sunday, December 3, 1972) when my brother and I faced a dilemma, a sort of Glasgow version of Sophie’s Choice. Senga’s Choice, perhaps?

We could wait for the end of the concert, thus missing the last bus to Busby. Or we could leave while Jimmy Page was bringing down bits of plaster with another solo that was causing gulls to tremble. In Skye.

The decision over whether to walk the seven miles home was given an added spice by the realisation that we would almost certainly be confronted by some mischievous ragamuffins at Gorbals Cross, armed with various illegal, sharp implements and a justifiable sense of grievance at what life had bequeathed them. We walked home, of course, Until we ran home, of course. The decision to stay was followed by the inevitable chase up towards Victoria Road that petered out in the manner of US sheriffs deciding not to cross county lines.

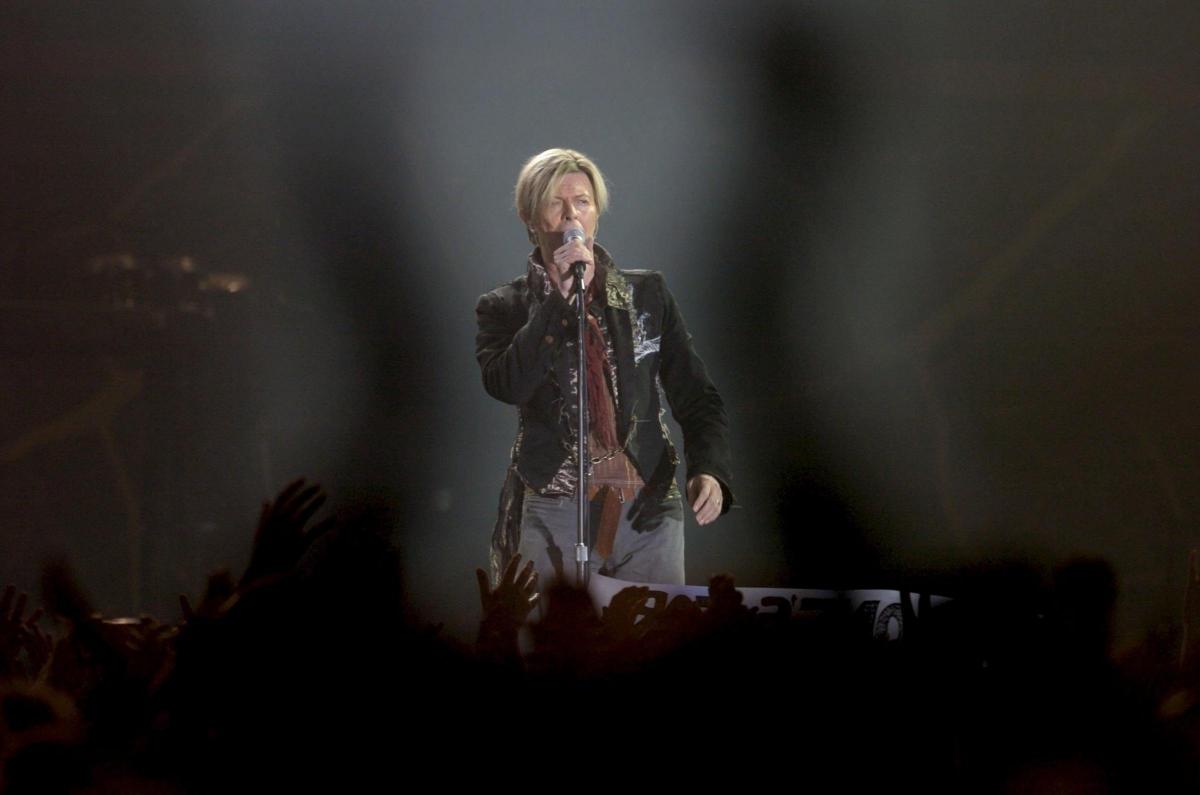

The retreat from a David Bowie (or more accurately Ziggy Stardust) concert of May 18, 1973, was more decorous. Google has supplied the date but somewhere in this auld napper is the solid remembrance of something shimmering, sensational and wondrously affecting.

READ MORE HUGH: Beware the deadly drugs dealer who comes disguised in a business suit

The intervening decades have added to that roll call of great concerts with Randy Newman, Bob Dylan, the Sensational Alex Harvey Band, Gillian Welch, the Drive-By Truckers and many others finding a niche in this dilapidated dome.

But there was a further realisation that drifted into consciousness as the snow fell like the contents of a rock band’s rider bowl. It was this: I miss gigs so bad that I miss the bad gigs.

These bad gigs have to meet certain criteria. First, one must look forward to them, thus ensuring the disappointment carries an ache. Second, the artist has to have an undeniable pedigree of work. Third, the bad gig must also prove to be a good gig for others.

Jeff Tweedy in the Glasgow Concert Hall ticked all these boxes. January 29, 2015, if you must know. I could build a tower worthy of downtown Dubai of my Tweedy CD collection: Uncle Tupelo, Wilco, his work with the magnificent Mavis Staples. But his set that night left me as cold as the Red Army outside Kursk. So anticipation had been mocked. Tweedy’s greatness had not been passed on to this listener on this night. It happens.

But the third condition was also realised. I stayed to the end. Retreat was not an option. This may be bad, I reflected, but I am not going to weaken. I survived. But when I emerged on to Buchanan Street I was engulfed by a group of mates who were so energised by what they had seen and heard that I genuinely wondered if they had been watching a Beatles reunion with an encore by Elvis and the TCB band.

I did not make any protestations. It would have been petty. They had won the lottery on a roll-over week. My winning ticket had been eaten by the dog. It was not the first time this has happened in my life. I was at ease with all of this.

Covid and concerts teach us that there may be a general communal experience but there is always the individual reaction. That almost instinctive reflex can be felt when listening to the radio in a Bearsden park or standing in the shadow of Donald Dewar’s statue and hearing the excited babble of the enthused.

Both remind me of what has been lost but may yet be recovered. I miss good gigs. I miss bad gigs.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel