You might not know it yet, and lock-down means your opportunity to explore it fully will be sadly limited when you do, but Thursday is the inaugural Gray Day, the first of what organisers hope will become a significant annual event celebrating the life, work and legacy of Alasdair Gray.

The iconic author, illustrator, poet and artist died aged 85 in 2019 and the plan is for Gray Day eventually to assume the same stature as its sort-of-namesake, Bloomsday. Named for Leopold Bloom, the protagonist of James Joyce’s 1922 Modernist masterpiece Ulysses, it’s held in Dublin every June and sees Dubliners attend readings and enjoy street parties and pub crawls dressed as characters from the book. Aside from being a big tourist draw and driver of revenue, it’s taken very seriously as a cultural event: on Bloomsday in 1982, Irish broadcaster RTE marked the centenary of Joyce’s birth with a continuous 30-hour broadcast of the entire text of Ulysses.

Joyce is an author with whom Gray is often compared, and the areas of Glasgow’s West End which formed the Scot’s stomping ground could become equally busy on Gray Days yet to come – though in pandemic-hit 2021 it’s the digital realm only which is playing host to the celebrations.

This year’s participants and onlookers are being asked to change their social media avatar to an image of Gray, and to post about what he and his work means to them using the hashtag #GrayDay. There will also be a focus on the art works by Gray which are held in the city collections and in the Alasdair Gray Archive. Other events scheduled include an evening of readings hosted by Neu Reekie, the vibrant, Edinburgh-based outfit run by writer-impresario Kevin Williamson and poet Michael Pedersen. Titled A Gray Day Broadcast, it’s a free online event promising appearances by Trainspotting actor Ewen Bremner, BBC Radio 6 Music DJ Gemma Cairney, Eugene Kelly of Glasgow indie legends The Vaselines, and writers Irvine Welsh, Denise Mina, Ali Smith and Yann Martel.

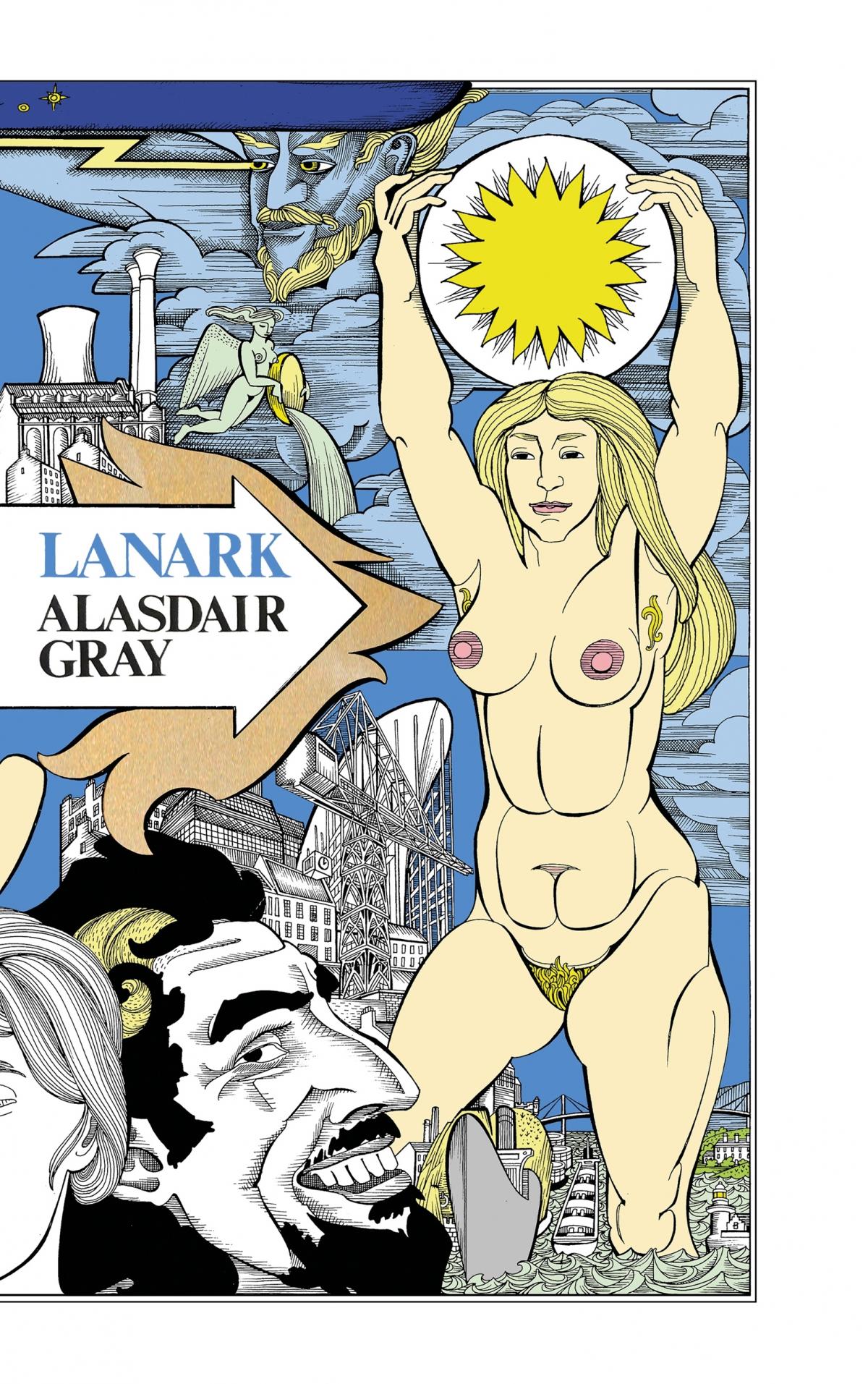

The choice of February 25 for this first Gray Day celebration is not random. Far from it. Thursday marks the 40th anniversary of the publication of Gray’s literary masterpiece Lanark by then-fledgling Edinburgh publishing house Canongate. As well as throwing their weight behind Gray Day, the company is re-issuing Lanark in a sumptuous hardback 40th anniversary edition alongside three other works.

For those unfamiliar with the novel and the story behind it, it’s quite a tale. A literary debut decades in the making, Lanark was already the stuff of legend when novelist William Boyd encountered Alasdair Gray in the early 1970s. At the time, Boyd was studying English at Glasgow University. “Lanark was talked about as an impossibly gargantuan, time-consuming labour of love, a thousand pages long, Glasgow’s Ulysses – such were the myths swirling about the book at the time,” he later wrote.

A decade or so on, shortly after the publication of his own first novel, Boyd found an early copy of the finished book in his hands and with it a commission from the Times Literary Supplement to write a review. They gave him 2000 words and Boyd’s critical summation ran on February 27 1981 under the headline ‘The theocracies of Unthank’, a reference to the fictitious (and fantastical) city which features as a cypher for Glasgow in two of the four books which make up the novel (which, by the way, opens with Book Three and contains a Prologue and an Epilogue that are not placed where you might traditionally expect them). The other two books follow Duncan Thaw, denizen of the real Glasgow, as he grows from boyhood to adulthood, though that synopsis doesn’t even begin to do justice to the hurly-burly of ideas and literary and textual experimentation which the book contains.

The actual publication had been marked two days earlier at a lunchtime party in Glasgow’s Third Eye Centre which invited guests to celebrate the launch of “a frequently announced novel by Alasdair Gray”. Needless to say the man himself designed and wrote the invitations, just as he provided the illustrations which pepper the novel, from the dense frontispieces introducing the individual books to the fake road signs, done in the bold style of 1970s motorway signage, which feature here and there: New Cumbernauld this way, straight on for Imber Unthank. That kind of thing.

Three years on from publication, Lanark had come to the attention of Anthony Burgess, author of A Clockwork Orange and no slouch when it came to recognising stellar literary talent. Burgess included Lanark in his influential 1984 work Ninety-Nine Novels, potted critiques of what he felt were the best books written in English since 1939. And so Gray found himself in exalted literary company sitting alongside authors such as Ernest Hemingway, JD Salinger, Aldous Huxley, Gore Vidal, Iris Murdoch, Vladimir Nabokov, Thomas Pynchon and James Joyce himself, to name just eight. Gray and Muriel Spark were the only Scots on the list.

Janice Galloway, author of Clara and The Trick Is To Keep Breathing, is one of six writers to feature alongside Gray in The Kelvingrove Eight, a photomontage by the artist Calum Colvin now held at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. She recalls first encountering Lanark at a friend’s house where she literally tripped over it – even in paper-back its near 600-page length makes it a handy doorstop. She then found her attention drawn to the cover, which showed items she was familiar with: the unmistakeable humps of the Forth Bridge, the famous paddle steamer Waverley, Glasgow Cathedral and the Necropolis overlooking Dennistoun. There were also tower blocks, factories, pylons and gasworks. What struck her most forcefully was that this was a book about “home”, one written in a language she understood, about people she felt she could walk down a city street and see.

“As though whispering aloud what I had always assumed a local secret, Gray spoke using the words, syntax and places of home,” she wrote on the 20th anniversary of Lanark’s publication, “yet he did it without the tang of apology or rude-mechanical humour, the Brigadoon tartanry or long-dead warrior chieftain stuff I had grown used to thinking were the options for how my nation appeared in print.” Gray’s Glasgow, in her eyes, “was a breathing, many-layered Glasgow that was not just an industrial warehouse for ships, but a resonant and fully-claimed city that could stand for the nation entire”.

Galloway captures and distils there what many people feel today about Lanark, and drives deep into the reasons why the novel has only increased in stature over the 40 years of its existence in print. Further intimations of that standing came in the welter of eulogies and superlatives which met the news of Gray’s death in December 2019. First Minister Nicola Sturgeon spoke about “the masterpiece that is Lanark” and called Gray “one of Scotland’s literary giants”. Val McDermid hailed his having “transformed our expectations of what Scottish literature could be” (and don’t think she didn’t have Lanark in mind). Ali Smith, four times shortlisted for the Booker Prize and once memorably described by Sebastian Barry as “Scotland’s Nobel laureate-in-waiting”, called Gray nothing less than “a modern-day William Blake”. She recalled hearing him read in Aberdeen when she was a teenager, a Eureka! moment she came away from “knowing that anything and everything” was possible in writing and that Scottish writing “was in revolution and Gray was the heart of a literary renaissance which revitalised everything.” In short, Alasdair Gray and his novel Lanark matter. A lot. To a great many people.

And so to Gray Day. The driving force behind it is Glasgow gallerist Sorcha Dallas, a long-time friend of Gray’s and the custodian of the Alasdair Gray Archive. She was instrumental in organising the city-wide retrospective held in 2014 to mark Gray’s 80th birthday which included an exhibition of 100 career-spanning works held at Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum plus attendant shows at Glasgow School of Art, where Gray studied in the 1950s, and the city’s Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA). It was when Dallas was approached by Canongate to help mark Lanark’s 40th anniversary that the idea of Gray Day was born.

“I would love it to become an annual event and to use the date to celebrate the breadth and scope of one of Scotland’s most important cultural polymaths,” she says. “Alasdair’s work spans so may mediums and forms that it feels only right to celebrate an aspect of this multi-faceted artist every year.”

Dallas first worked with Gray in 2008 when she was running her commercial gallery, but she had long been aware of his work as both writer and artist and of how it “permeated through the West End of Glasgow, an area I’ve lived most of my adult life”. She would see occasional snatched glimpses through tenement windows of paintings by him, and there were more public works to view, such as his celebrated murals in The Ubiquitous Chip restaurant.

As for Lanark, reading it was something akin to a rite of passage. “I first read it as a painting student at Glasgow School of Art in the late 1990s,” she says. “It was a key text and cited as a constant source of inspiration for many artists and writers who were working and living in the city. I found it incredible how he used the recognisable city in which I lived as a starting point to discuss more universal themes. Its ambition and scope felt exciting to encounter and made me want to read more.”

She re-read it recently. Has anything changed? “I had a very different response to it having known and worked with Alasdair, made more poignant by the fact that he’s no longer here,” she admits. “I’ve been immersed in Alasdair’s life and work for so many years that the book resonates in a different way. I can make links across space and form with other books and art works he has made, so the book now feels richer as a result. I also appreciate his clarity of language and how he strived to do this with word and line, to distil words and images into their purest form.”

In the run-up to Gray Day, Dallas has been posting video clips titled Gray Of The Day in which various people read from Lanark. Among those who have recorded a reading is Katie Bruce, Producer Curator at the Gallery of Modern Art in Glasgow and one of the people involved in that 2014 retrospective.

Like Dallas, she first encountered Lanark at art school in the early 1990s. “What it meant to me as a student when it had only been out for 10 years, and what it means now are different readings,” she says. “I suppose that’s the joy of going back to a book like Lanark because depending on where you are in your life, you read different things into it every time”.

She too has high hopes for future iterations of Gray Day. “It would be lovely to see commissions come out of it, or memories, or archives being opened up further. A lot of the work we have by Alasdair isn’t permanently on show because it’s on paper and you can’t do that. But we have an accessible store, so an annual pilgrimage to see important works by him in that space would be really great.”

Looking forward into the post-pandemic future she sees Gray Day most of all becoming a way to celebrate Alasdair Gray’s ideas and principles – about making art, about representations of Scotland and Scottish life – and about his continuing influence on Scottish cultural life and the city in which he lived and worked. “Doing it on the anniversary of the publication of Lanark is key because a lot of artists cite that book in terms of thinking about art.”

See you in Glasgow, then. Same time next year?

What they said about Lanark …

“Scotland produced, in Hugh MacDiarmid, the greatest poet of the century (or so some believe); it was time Scotland produced a shattering work of fiction in the modern idiom. This is it.”

Anthony Burgess, 1984

“Just as Joyce fitted an ordinary day in Dublin into the armature of the Odyssey, so Gray reconfigures the life of Duncan Thaw into a polyphonic Divina Commedia of Scotland. The Joyce comparison is valid on many levels and I think provides an insight into Gray’s approach and methodology as a novelist.”

William Boyd, 2011

“It is a quirky, crypto-Calvinist Divine Comedy, often harsh but never mean, always honest but not always wise. Certainly it should be widely read; it should be given every chance to reach those readers – for there will surely be some, and not all of them Scots – to whom it will be, for a short time or a lifetime, the one book they would not do without.”

John Crowley in the New York Times, 1985

“The fact that Lanark had come from Scotland was like a door opening. It was a shock. You just didn’t think that things like that could come from here, and the fact that this one had was dizzying.”

David Greig, 2015

“Gray spoke using the words, syntax and places of home, yet he did it without the tang of apology or rude-mechanical humour, the Brigadoon tartanry or long-dead warrior chieftain stuff I had grown used to thinking were the options for how my nation appeared in print. Neither had he chosen the heather-strewn hills, the dank glens, the isles or the fishing communities as his location. With its Royal Infirmary cupolas and Victorian Great Western road, its Blackhill kids and the Clyde widening out to the sea, the place in which this epic would reveal itself was Glasgow, a breathing, many-layered Glasgow.”

Janice Galloway, 2002

“For a while before I held a copy I imagined it like a large paper brick of 600 pages, well bound, a thousand of them to be spread through Britain. I felt that each copy was my true body with my soul inside, and that the animal my friends called Alasdair Gray was a no-longer essential form of after-birth. I enjoyed that sensation. It was a safe feeling.”

Alasdair Gray, 2001

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here