Lorne Jackson

THUMP! Thump! Thump!

The punches hit home.

Thump! Thump! Thump!

David Puttnam was being battered on his back. Hard.

Which might have been a problem if he had been lurking in a darkened alley, getting bludgeoned by a bloke in a balaclava with a bad attitude.

But that was not the case. Instead, he was in a lofty theatre that was positively a-dazzle with lights from the stage.

There was another glow, too. The showbiz shimmer that sparks when ever a large group of A-List celebrities rub up against one another in the same room.

Puttnam was seated at the Academy Awards ceremony. And the bloke beating on his back as though it was a conga drum? Steven Spielberg. (Yes, that Steven Spielberg.) Who was trying, perhaps a little too enthusiastically, to catch his fellow movie maker’s attention.

“I think you’re going to win,” grinned Spielberg when Puttnam turned round in his chair. “I really think you’re going to win.”

Spielberg was right. Chariots of Fire, the film Puttnam had recently produced, grabbed the Academy Award for Best Film that evening.

The movie, which celebrates its 40th anniversary this year, also won three other statuettes at the glittering ceremony. Best costume design, best original screenplay and best original score.

In the four decades since its release it has become a classic of cinema, and with good reason, being an extraordinary story based on real events, with almost universal appeal.

It has also managed to weave itself into the great tapestry of tales that Scotland tells about itself, every bit as significant to the nation’s mythological make up as Mel Gibson’s Braveheart.

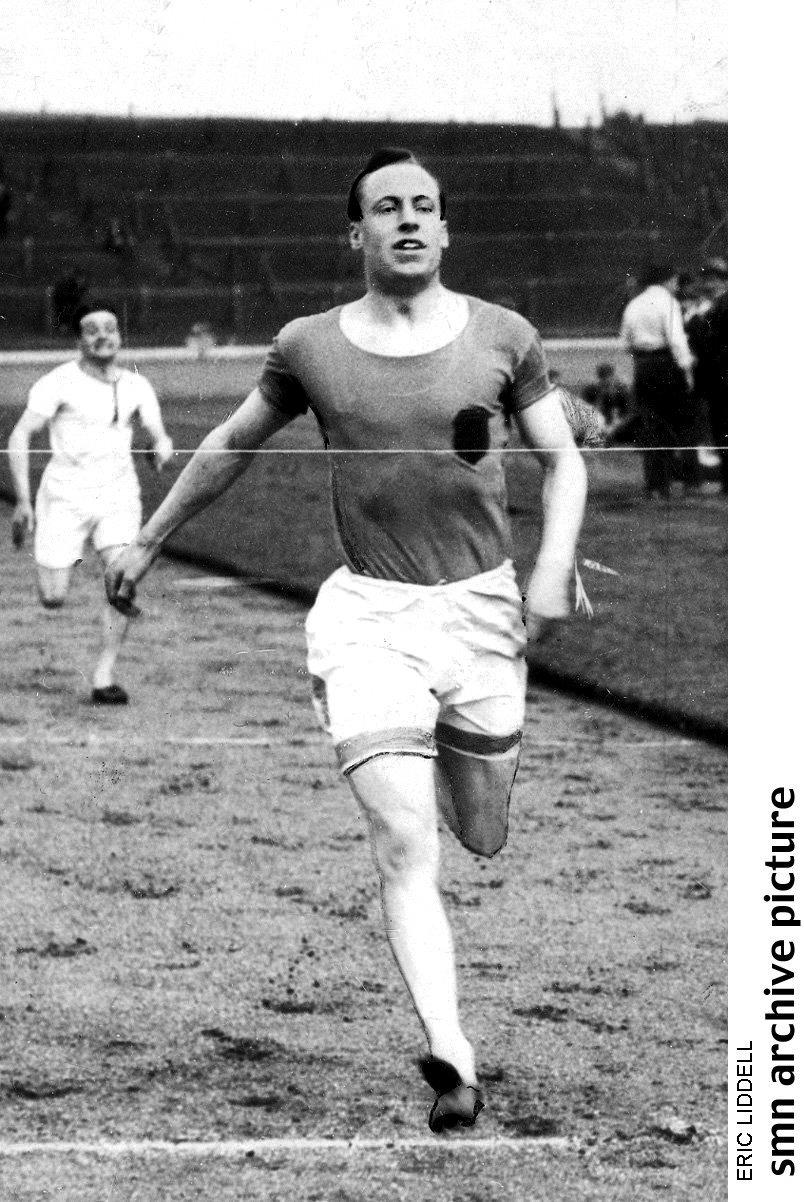

The narrative concerns two athletes competing at the 1924 Olympics in Paris, the Englishman Harold Abrahams and the Scot Eric Liddell.

Liddell is the more obviously heroic of the two protagonists. A devoutly religious Christian, he refuses to compete in the 100 metres Olympic final after discovering it will take place on the sabbath.

Offered the chance to race in the 400 metres instead, he… (if you haven’t seen the movie and don’t want it spoiled for you, close your eyes – NOW)… goes on to win gold.

And on the subject of all things glittery and priceless, Puttnam proceeds to tell me exactly what it feels like to bag an Oscar for Best Film.

“It was very odd,” he chuckles. “I genuinely didn’t think I was going to win that evening, so I hadn’t prepared a speech. As I took to the stage I kept thinking to myself, I wish I’d at least got my hair cut.

“I was also very conscious of the slippery-looking steps. The last thing I wanted was to trip over. Then, when I was standing on the stage, I spotted that the red velvet covering the podium had been put on crooked. I remember thinking: ‘How weird. They’ve gone to all this trouble and nobody bothered to put the velvet on straight.’ That’s what I was thinking about as I received my Oscar.”

Puttnam’s long journey towards that date with destiny and a squint cutting of velvet began relatively inauspiciously, three years earlier.

As a movie producer he was already making a name for himself with cinematic offerings such as Bugsy Malone, a prohibition musical made with child actors, and the gritty Midnight Express, about an American drug smuggler jailed in a harsh Turkish prison.

Then, one day, the 37-year-old English film producer found himself bedridden with flu in a rented Hollywood house. Bored, he searched for reading material on the shelves. Mostly he found books on yachting, which didn’t interest him. (Which is lucky for film buffs. Otherwise they might have found themselves watching a Puttnam blockbuster called Posh Boats Bobbing About In A Bay.)

Eventually Puttnam stumbled upon a musty old history book about the Olympic Games. In the volume he spotted a brief paragraph about a Scottish sprinter he had never heard of who was willing to sacrifice glory for faith.

“I thought it was an extraordinary story,” recalls Puttnam.

He contacted the actor and writer Colin Welland, who started developing a script, which initially went by the rather prosaic title of Runners. Up and coming film maker Hugh Hudson was brought in to direct.

The Chariot race had begun in earnest, though it would be a wearying process, as film production always is. More of a marathon than a Liddell-like sprint.

Puttnam says working for lengthy periods on a project is like a marriage. “Sometimes it’s a pain in the a**e, and you think: ‘Do I really need this?’ But you’ve fallen in love with something and you can’t let it go.”

What drew him to the story was Liddell’s rigid moral code, though another of the sprinter’s qualities also appealed.

“Would I have cared about Liddell if he had lost the race?” muses Puttnam. “The answer is – no.”

Though Liddell’s surety of purpose eventually became problematic when it came to the script. A compelling narrative usually has at its heart a character beset with inner conflicts who goes on a psychological journey of discovery. But Liddell always knew who he was and where he was headed.

“That made it extremely difficult,” admits Puttnam. “It was easier with our other lead character, Liddell’s fellow British racer, Harold Abrahams, who actually probably wasn’t a particularly nice person, and was very hubristic.

“But when ever we talked to people who had known Eric, all we ever heard was that he was an absolutely wonderful man.”

Liddell was indeed an exceptionally decent fellow. After winning his Olympic gold he moved to China, where he had been born to missionary parents, and continued the family work until he died in a Japanese civilian internment camp in 1945.

The broadcaster Sally Magnusson, who published the biography The Flying Scotsman: The Eric Liddell Story four decades ago to coincide with the release of the movie, researched her book by interviewing the people closest to Eric, including his wife Florence, who at the time lived in Canada.

One of the crucial questions she asked was if Ian Charleson, who played the Scottish sprinter in the film, was anything like her husband.

“Florence said that Ian had captured the essence of him,” recalls Sally. “He had caught his charm, his charisma, his lack of sanctimony, his lack of holiness. He was good fun. He was mischievous.”

However, Charleson didn’t physically resemble Liddell. Yet it is the role that the actor, who tragically died from AIDS in 1990, will forever be identified.

Like Liddell, Charleson was a graduate of Edinburgh University, and he was similarly charismatic, forging a distinguished stage career, with many standout performances in a wide variety of productions. He excelled in everything from musical theatre to Shakespeare. Yet he never became a major movie star, even though Chariots of Fire was a hit around the world, including in the States.

“He was a wonderful actor, but his heart really was on the stage,” says Puttnam. “Also he didn’t show any interest in Los Angeles. When we all went out for the Oscars there was never a sense that Ian might stay. He was never starry.”

After that heady Oscar win Puttnam continued to produce movies, and was briefly in charge of a major Hollywood studio, Columbia Pictures. He later returned to the UK and worked closely with the Labour Party, and was rewarded with a seat in the House of Lords where he became Baron Puttnam. Now 80 years old, he lives in Ireland and continues to be passionate about film.

How does he think Chariots of Fire compares to modern epic movies about heroism, which tend to be about strapping men and women who wear capes, fly and have laser beams shooting out of their eyeballs?

“The problem with superhero movies is they’re not about anyone you know,” sighs Puttnam. “You’ve never met anybody who can survive leaping off a high building, nor have I. And the result of all these films is that you end up with Donald Trump, because people end up thinking ridiculous things have some reality to them.”

He adds: “Life is painful. Being a human is one of the hardest gigs imaginable. And films like Chariots of Fire touch you, and tell you life’s not easy. But you can win.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel