The alarm was raised early on Boxing Day. Police patrol cars were ordered to be on the look-out for a Ford Anglia saloon, which was last seen at 5.15am; the car’s occupants were thought to be a man and a woman “said to have Scottish accents”.

Hotels, boarding houses, and restaurants were searched by the CID. Road blocks were set up on the routes into Scotland. The authorities were determined the perpetrators should not escape from London. There had been warnings in the past that something like this might happen. And now it had.

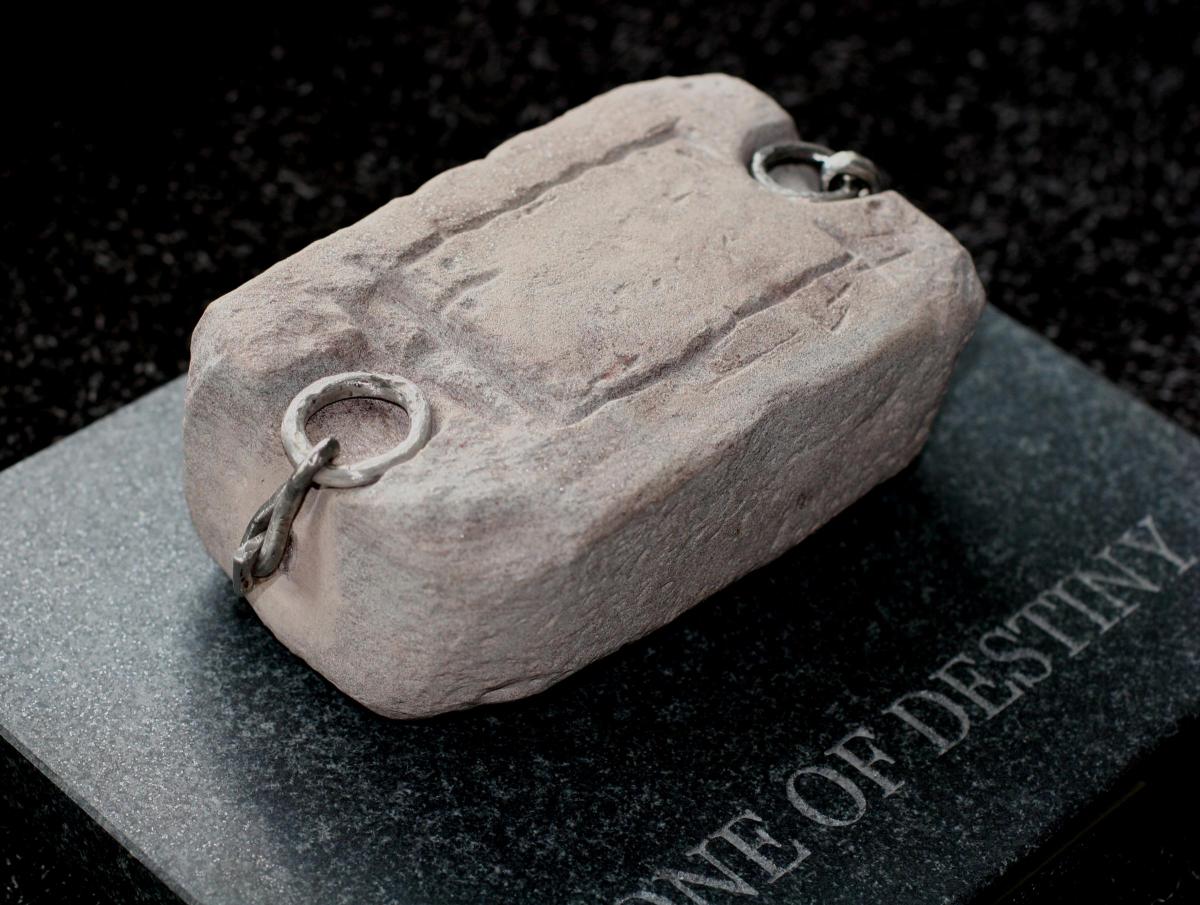

Seventy years on, the Stone of Destiny and its removal – or “liberation”, “theft”, “restoration”, whichever word you prefer – from Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day 1950 has become one of the most dramatic episodes in the history of Scotland’s constitutional affairs.

We know who did it, and how, and we know how it was recovered, on April 11th, 1951, exactly 70 years ago tomorrow. But what we still don’t know really is how the story ends. With the argument on independence raging fiercer than ever, are there lessons still to be learned from an innocent oblong block of pale yellow sandstone?

The person to ask is Ian Hamilton, the last surviving member of the group that took the stone, and I’m going to ask him, but first we should delve into the details of the stone’s removal and return, because the reports of the time are a remarkable testimony that reveal what’s changed in 70 years and what hasn’t.

Just a few hours after the stone disappeared, The Glasgow Herald reported that the police and abbey authorities believed it had been taken by Scottish “patriots” in a bid to restore it to its “rightful” home. The report also quoted Alan Don, dean of the abbey, who said “wild” Scotsmen had threatened him in the past that the stone would be removed.

The constitutional, legal, and political implications were obvious straight away. In the immediate aftermath of the theft, a lawyer told The Glasgow Herald that the people who took the stone were guilty of the crime of sacrilege, the “breaking into a place of worship and stealing therefrom”, and that under English law the maximum penalty was a long term of imprisonment.

However, everyone knew it wasn’t quite as simple as that because the stone had always been the centre of political disquiet and efforts to return it to Scotland. The Scottish Labour MP Davie Kirkwood proposed a bill for its return in 1924; the slab of sandstone was a symbol of Scottish nationhood, he said, a venerable relic.

There had also been plans for more direct action: on one occasion, the poet Hugh MacDiarmid travelled to London with the intention of liberating the stone but later had to admit to his co-conspirators that the money set aside for the scheme had been spent in the pub instead.

In the days after the stone’s removal in 1950, prominent figures in the home rule movement discussed the possible consequences. The writer and devolutionist Nigel Tranter said it would awaken dormant feelings in Scotland. “This venture may appear foolish and childish on the surface,” he said, “but it will have the effect down south of focusing attention on Scotland’s complaints.”

John MacCormick, chairman of the Scottish Covenant Association, which promoted a petition calling for home rule, also said that “whatever the outcome of the present adventure” he hoped the stone would ultimately be kept in Scotland except on coronation occasions. The Stone of Destiny, he said, properly belonged to the people of Scotland.

It has to be said that the evidence for his claim was undeniable, although there is a good deal of myth in the story as well as fact. The stone was allegedly brought to Scotland by Gaythelus, ancestor of the Gaels, who was married to Scota, daughter of an Egyptian pharaoh. The first enthronement of a Scottish King to be recorded in detail – that of eight-year-old Alexander III – states that he was hailed by a seanchaidh, or bard, and that he was not crowned but “set on the Stone”. The stone had become a symbol of Scottish kingship and power.

So it makes perfect sense that, some 50 years later, Edward I wanted to remove the stone when he invaded Scotland in 1296. King John, who had succeeded Alexander, was forced to abdicate, a great many nobles were sent south in captivity, and the Stone of Destiny was taken to Westminster Abbey.

Edward’s message to the Scots was clear: your independence is at an end, and so, without intending to, the Hammer of the Scots transformed the Stone into something else: a symbol for the removal – but also the possible restoration – of Scottish power.

It wasn’t long, even then, before there was pressure to return it, which is where a Scottish wedding in the summer of 1328 comes into the story. The father of the groom, King Robert I of Scotland, had spent over £2,400 on the food and booze so it promised to be quite a party but it was also primarily, as royal weddings were then, a political move, which is why David, the groom and Robert’s heir, was four years old and Joan, the bride and sister of Edward III, was seven. The wedding was supposed to mark an end to more than 30 years of war between Scots and between Scots and the English and part of the deal was that the Stone of Destiny would be returned to King Robert.

However, the plans fell apart. A crowd gathered in London and clamoured against the removal of the Westminster war trophies – which included the stone but also the Black Rood, or Cross, of St Margaret, a symbol of the holy status of the Scottish monarchy – and the agreement to return the stone was never observed.

The first king of a united Scotland and England to be crowned on it was James VI and I. Elizabeth was also “set on the Stone” in 1953, just three years after it was taken from the Abbey.

In the weeks that followed its removal, there was much debate in Scotland about its fate and significance.

An editorial in The Glasgow Herald on April 3, 1951, appealed for the perpetrators to come forward and suggested they should be shown leniency. “It is undesirable that those who carried off the stone should be given grounds for posing as martyrs,” it said. “It is no less undesirable that, through total exemption from the consequences of their foolish behaviour, they should appear to be accorded the status of popular heroes which they in no way deserve.”

It concluded that in spite of the activity of nationalist publicists, the attempt to build up an irresponsible action – the theft of the stone – into a feat of considered patriotism had failed.

Just a few days later, on April 11th, the stone was returned in a highly choreographed event. Its custodians arrived at Arbroath Abbey and took the stone up the main aisle of the ruined building where Scotland’s declaration of independence was signed on April 6, 1320.

They laid the stone at the high altar, and placed on the stone a letter addressed to the King. The letter said that they had intended no indignity or injury to His Majesty and had been inspired by a desire to compel the attention of His Majesty’s ministers to the widely expressed demand of the Scottish people for a measure of self-government.

As soon as the police arrived, the stone was whisked off to Forfar police HQ, then Glasgow, then London, and the question then was what should be done with the instigators: four Glasgow students: Gavin Vernon, Kay Matheson, and Alan Stuart and their leader Ian Hamilton.

The matter was raised in Cabinet, where there was discussion of whether the foursome should be prosecuted and also whether the stone should be re-housed in Scotland. Like The Glasgow Herald had done a few days before, the Attorney General Hartley Shawcross warned against prosecution because it would give the students the chance to be seen as martyrs if they were convicted or heroes if they were acquitted.

As for Ian Hamilton himself, who’s 96 now, he believed that the incident changed the discussion around Scotland, although 70 years on, he has a complicated relationship with the whole affair.

When I called him at his home in the Highlands, he admitted that he could sometimes get a little tired of his association with the stone and the fame it has brought him.

“It gives a licence to people you don’t know to stop you in the street and they’ve only one subject: the stone,” he said. “Youngsters want to be famous, but it’s a rotten thing.”

Mr Hamilton does, however, still recognise the symbolic power of the stone. He isn’t entirely certain where his sense of nationalism and support from independence came from, although he does remember unsuccessfully volunteering to be a pilot during the Second World War.

“Anyone who holds belief, I doubt if they’d be able to tell you where the beliefs come from,” he says, “But that left me with a positive sense of being shut out.”

Mr Hamilton also recognised – then and now – what he calls the power of icons like the stone; “in an industrialised and largely automated society, icons are needed more than ever,” he says. And so as a young man, a young nationalist, he and his three comrades did the long drive to London, crowbarred open a door to the abbey, and manhandled the stone into their car (famously, they managed to drop it in the process and break it in two).

As for Mr Hamilton’s assessment of what changed when the stone was taken, he says the change took time.

He reminds me just how low was the low ebb of nationalism at the time and he certainly had no affinity with the SNP.

“I couldn’t even join the SNP,” he says, “because all they did in those days was sing songs about Bonnie Prince Charlie. If I’d been asked in 1746, I’d have said who the hell wants to bring the Stuarts back?”

Basically, nationalists, he says, were on the fringes of the debate and in the eyes of some people, were nothing more than a rump of extremists.

But the point is: in England or Scotland, the power of the stone endured and by the 1990s the then Scottish Secretary Michael Forsyth proposed its return.

The Prime Minister of the time, John Major, was initially non-committal but says in his memoirs that events began to make the return look more attractive.

“The public records about the theft of the stone in 1950 by Scottish nationalists were soon due for release,” he said. “This raised an issue, which had been quiescent, and provided a focus for a nationalist grievance, whether we wished it or not. Moreover, as 1996 was the 700th anniversary of the stone’s original removal from Scotland by Edward I, its profile would be raised even higher.”

And so John Major concluded that, logically and legally, Scotland had a case for the return of the stone; he also wanted to forestall a row over the artefact and so let it return.

“Today,” he says, “the stone is back where I came to believe it belongs. It returned on St Andrew’s Day 1996, to a dignified reception from the Scottish establishment and a churlish one from those who doubted the government’s motives.”

In the years since, the stone has been in the Crown Room of Edinburgh Castle, but there has always been a debate about whether that is quite the right place.

Historically, the stone was kept at Scone in Perthshire, where Scotland’s monarchs were crowned, and it was announced last year that to Perthshire it would return. From 2024, the stone will be displayed in Perth’s new city hall and municipal museum.

For Scots – nationalists and unionists alike – this seems like the right move. Ian Hamilton said it was common sense and the Conservative MSP Murdo Fraser also welcomed the move after campaigning for it for some time. “I believe the stone has one more journey to make,” he said, “back to its historic home in Perth and Kinross.”

Which only leaves the question of whether the stone still has some of its power left. As Ian Hamilton pointed out, when he and his friends took the stone from Westminster Abbey, nationalism was at a low ebb, it was on the fringes, but 25 years after its return to Scotland, support for independence is at a historic high point.

There is a prophecy which says that wherever the stone rests, Scottish rule will be supreme. Did the prophecy come true when the Scottish Stuarts inherited the throne of England? And, for those who dream of independence, could the prophecy come true again?

STORY OF THE STONE

The Stone of Destiny, otherwise known as Stone of Scone, or in Gaelic Lia Fail, is a block of pale yellow sandstone measuring around 26in by 16in and weighing around 340 pounds.

According to legend, it was brought to Scotland by Gaythelus, ancestor of the Gaels, who was married to Scota, an Egyptian princess.

It was traditionally kept at Scone where John de Balliol was the last Scottish king crowned to be crowned on it, in 1292. Four years later, it was seized by Edward I and taken to England.

Under the terms of the Treaty of Northampton in 1328, which ended the Scottish war of independence, the stone was to be returned to Scotland, but it never happened and remained in England until 1996 (with some time in Scotland after it was taken from the Abbey in the 1950s)

The stone is now in Edinburgh Castle but will be moved to Perth City Hall in 2024.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel