SEE/SAW: Looking at Photographs

Geoff Dyer

Canongate, £15.99

Review by David Pratt

Back in a bygone day before entering journalism via documentary photography, I taught art history and critical studies at Glasgow School of Art. Even before then, during my student days at the school, I was a devoted follower of the art critic, painter, and novelist John Berger. His book, Ways of Seeing, was a virtual bible for a generation of art students and those teaching in art schools.

In part inspired by the thinking that underpins the book, I used to set my students an exercise by asking them to bring with them a selection of picture postcards. Many were of the typical holiday type commonly posted in those pre-internet days. Seascapes, landscapes, city scenes, portraits, monuments; others were more human in their imagery – comic or political.

With the postcards pinned to the wall, each image in turn was “read” by the students in terms of its content and formal qualities. Colour or monochrome, lighting, composition, the subject matter, time, place, what each photograph conjured up in terms of the imagination, were among the topics explored during such sessions.

The students' personal “readings” of the images were always fascinating and idiosyncratic. Each was often amazed at how much they could unpack by placing even the most seemingly visually mundane photograph under such scrutiny. This was, as Berger himself would have said, not just about looking but seeing.

I recite this anecdote because it’s the easiest and most accessible way I can think of to describe the process that Geoff Dyer undertakes in his latest book, SEE/SAW: Looking at Photographs.

As might be expected from an author and essayist who defies pigeon-holing in terms of genre, and is widely acknowledged as one of the world’s most respected writers on photography, Dyer utilises this process with great intellectual dexterity, gravitas and personal flair. There’s also a sprinkling of the humour that has become the leitmotif of a writer who has already published two other highly respected studies of photography and photographers. The first of these was The Ongoing Moment and the second, The Street Philosophy of Garry Winogrand: a collection of discursive essays about an image-maker who in the 1960s almost defined street photography.

Dyer’s latest book expands on many of the themes in these previous collections. It brings together essays that span a decade of writing, many of which were originally published individually elsewhere such as the New York Times Magazine’s On Photography column or Dyer’s Exposure column in the New Republic magazine.

The first section of the book, entitled Encounters, sees a sort of chronological approach with essays on individual photographers and related themes, be it the depiction of Paris by the great Eugene Atget, or examining the American photographer William Eggleston, renowned for his colour work through the unusual perspective of the images he rendered in black and white.

In each, a single image – such as Helen Levitt's photograph of children playing with a broken mirror in a New York street – acts as a starting point that is scrutinised in detail.

This forensic exploration of individual images is fascinating, but it’s when Dyer indulges in aesthetic and intellectual flights of fancy, letting his reading of a photograph be shaped and juxtaposed with painting, literary or political references, that I enjoy his writing most.

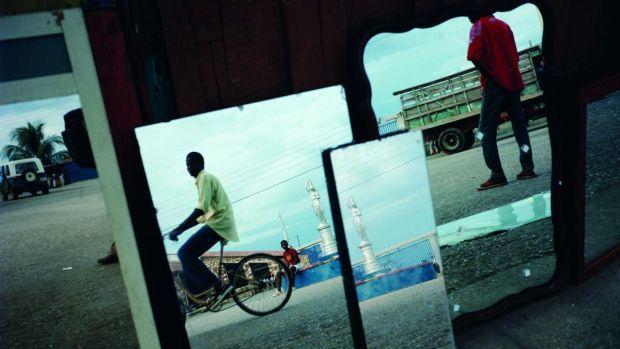

There is a striking example of this in the book’s second section, Exposures: a collection of 10 essays on photos from the news. In one, he discusses a powerful photo-journalistic image by Gary Knight, depicting the chaotic scene following an attack on US soldiers in Iraq. This, Dyer does through the prism of historic paintings by the likes of French artists Eugene Delacroix and Jacques-Louis David. Likewise, the Haitian images of one of my own favourite photographers, Alex Webb, are seen in the context of the colour and tropical landscapes that drew the likes of Paul Gauguin to Martinique and Polynesia.

Dyer also examines Webb’s use of shadow and his layering of compositional components – for example, his use of mirrors that had been placed by a roadside to photograph a street scene in Cap Haitien, Haiti. As Dyer says of Webb’s work, it “ends up in a Bermuda triangle where the distinctions between photojournalism, documentary and art blur and disappear”.

If all this sounds rather esoteric and off-putting, rest assured Dyer is way too good a writer to allow that to happen. Instead, the reader is taken on a visual and intellectual journey, so that once you have read Dyer’s words, you return to the photograph he describes, seeing it afresh and in ways that you might never have considered on first viewing.

A perfect example is London East End-based documentary photographer Chris Dorley-Brown’s picture, Sandringham Road & Kingsland Road 10.42am-11.37am, which takes on a whole new intimate significance after reading Dyer’s essay.

This again is where he is very much in the tradition of Berger, and other great writers on photography such as American Susan Sontag, whose 1977 book On Photography, was as much a critic’s classic and bible as Berger’s Ways of Seeing when I was student and remains so today.

Indeed, the work of Dyer's forbears such as photography critics Berger, Sontag and the French writer Roland Barthes is examined in the book’s third section, entitled Writers.

In all, this is a compelling collection of Dyer's work, though if there’s one aspect of the book about which I’m less convinced, it’s the design and binding. Physically it reminds me of a recipe book with its spine that folds back flat. Not sure it’s quite the look required for a book that contains so many exquisitely crafted words and individual photographs. Most people I have shown the book to like it, so perhaps I'm being pernickety in finding the layout to be strangely pedestrian and a little flat.

So, who will this book appeal too? Well, fans of Dyer’s writing, photographers like myself and those with a wider interest in the subject will undoubtedly wallow in it. However, it deserves a broader readership. Photography surrounds us and anyone who takes the time to delve into these essays, will find themselves in future not so much looking at photographs as seeing them in a way they have never done before.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel