It covered 73 acres of prime Glasgow parkland, racked up over 11 million visits, had a switchback railway and a water chute, was opened by King Edward VII’s daughter Princess Louise using a special golden key and even hosted its own eight team football tournament (Rangers beat Third Lanark in the semi before besting Celtic in the final). Then, after just six months, it was torn all down. Or most of it, anyway.

‘It’ was the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1901, which opened in Kelvingrove Park on May 2 – 120 years ago tomorrow – and ran until late autumn. It cost £373,000, took gate receipts of £404,000 and was one of that type of event which history now knows as a World’s Fair.

The first of these was held in 1791 in Prague as a way of marking the coronation of Leopold II (he only ruled for two years but had three coronations). The inaugural British World’s Fair was the Great Exhibition of 1851, held in a building in Hyde Park known as the Crystal Palace. By the end of the 19th century there were half a dozen every year and they were less concerned with marking the comings and goings of emperors and monarchs than with celebrating enterprise, industry, progress and manufacturing pizzazz. And so on into the start of the 20th century. Besides Glasgow, a World’s Fair-hopping tour of 1901 would have taken you to Vienna, Bendigo in Australia, and the American cities of Charleston and Buffalo where, on September 6, you might have witnessed the assassination of US President William McKinley by the anarchist Leon Czolgosz.

Nothing so startling happened in Glasgow. Here the entertainment involved concerts, organ recitals, exhibitions of machinery, a working farm, collections of art, examples of architecture from countries such as Russia and Japan, light displays and theatre performances. After paying your shilling entrance fee you could take a walk around a poultry exhibition, go straight into a concert by the Roumanian Orchestra, follow that with a Gymkhana display such as the one conducted by the Glasgow Ladies Cycling Club and then head for the Grand Hall to hear the great Dame Nellie Melba sing. That event was ticket only so if it was sold out, you could instead enjoyed a ride on the River Kelvin instead, courtesy of a Venetian gondola and its crew of real Venetian gondoliers. The Exhibition opened its doors at 9.30am and closed at 10pm with a light show. There were restaurants, tea rooms and a tobacco kiosk, and if you needed to spend a penny the public lavatories were plainly marked in black on the Official Guide.

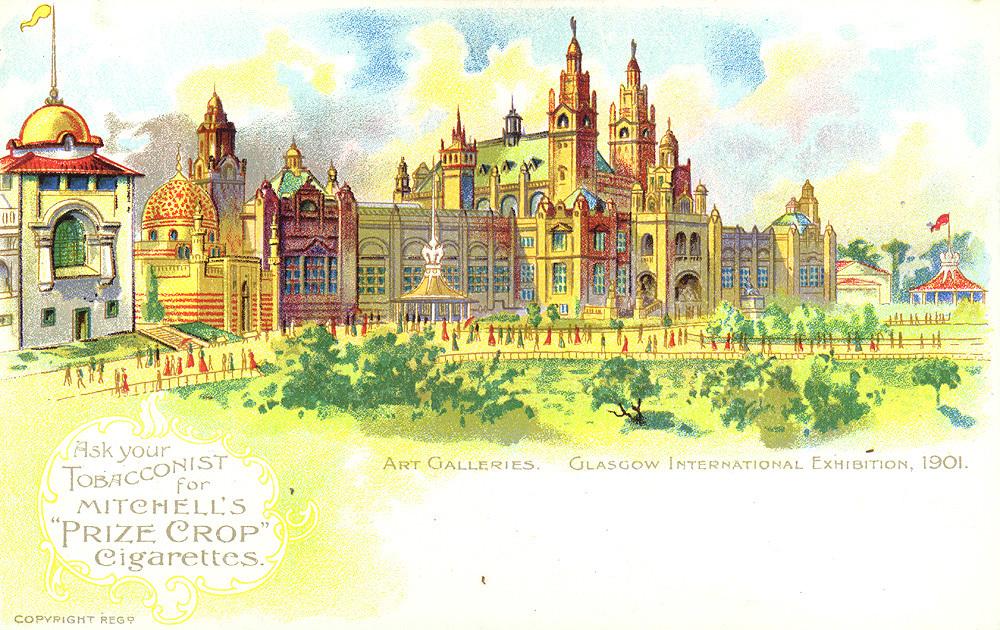

Among the bricks and mortar highlights were an extraordinary saucer-shaped concert hall which held 3000 people, pavilions showcasing cutting-edge architecture from around the world and a Machinery Section built on the site of what would become the Kelvin Hall. But the two showpiece buildings were the Palace of Fine Arts, designed by Sir John William Simpson and built in a Spanish Baroque style using red sandstone, and the nearby Industrial Hall. It was designed by Scottish architect James Miller, also responsible for the world famous Wemyss Bay railway station. A bling-tastic mash up of influences from Spain, Turkey and Venetian, it had a white façade and a gold dome and dwarfed Simpson’s creation. Topping the dome was a golden angel holding a torch lit using electricity – a cute touch as the city was in the process of expanding the city’s supply and electrifying the trams.

Much of the eastern end of the Industrial Hall was given over to what was called ‘the Women’s Section’. It included displays of weaving, sewing and cookery as well as more unusual past-times such as photography and bookbinding, and was divided into sections with names devoted to nursing, education, science, trade, philanthropy, literature and music.

Among the big names featured in the exhibition in the Palace of Arts were Edwin Landseer, Henry Raeburn, JMW Turner, John Constable, James McNeill Whistler and William McTaggart. It wasn’t entirely a boy’s club, though. A Mrs A Stokes lent her own work, The Net-Mender, one Bessie McNicol lent her painting Apple Blossom, and a Miss SRL Dean’s contribution was an oil colour titled Neil Munro, Esq.

New York’s Metropolitan Museum holds a copy of the catalogue for the exhibition and beside some of the paintings an unknown hand has apportioned star ratings in pencil. Everyone’s a critic, right? Perhaps more revealing about Glasgow life at the dawn of the 20th century are the catalogue’s advertisements. Alongside ones for hotels, booksellers, picture-framers and gallerists you’ll find adverts for the Anglo-Parisian School of Dresscutting, Dressmaking And Millinery (run by ‘proprietrix’ Madame Grohé), and a full page display promoting Waterhouse & Co. of 220 Sauchiehall Street. If you wanted “High class artificial teeth”, they were the people to see.

All that remains of this Edwardian Disneyland are the Sunlight Cottages, those architectural curious sited near Glasgow University, and the Palace of Fine Arts, though today we know it as Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum. It was always intended to have a life beyond the Exhibition and had been built using the £130,000 raised from a previous World's Fair in Kelvingrove Park, the 1888 International Exhibition Of Science, Art And Industry. That figure was then topped up by a public subscription fund, the Edwardian version of a Kickstarter campaign.

The grand Industrial Hall, also known as the Eastern Palace, is lost. Like most of the rest of the buildings it was pulled down after the Exhibition closed in late 1901. All that's left are glimpses and fragments – in oil paintings such as the one by Harry Spence showing it peeking out from behind a smaller pavilion, or in ghostly archival photographs of the interior like the one showing the huge space under the Grand Dome. A popular meeting place, it was decorated in violet, red and green – the black and white images don’t do it justice – and dominated by a statue of Edward VII which was not well liked. Its being 18 feet high may have contributed.

But as much as this is a story of what was and now isn’t, it’s also a tale of what might have been but never was. James Miller won the choice prize which was the commission to design the Industrial Hall, but a failed entry from the Glasgow firm of Honeyman and Keppie bears the unmistakeable hallmark of its most famous employee: Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Today the outstanding example of the built legacy of Scotland’s architectural genius is Glasgow’s iconic art school – but how much greater would that legacy be if his Industrial Hall had been built instead of Miller’s? Then again, imagine the collective civic soul-searching and angst we'd feel today if, like Miller’s building, it had been torn down after just six months of use.

The Glasgow International Exhibition closed on November 9 1901. Despite early concerns that there might be outbreaks of drunkenness and unrest during it – boozing in Kelvingrove Park? Surely not – the six months passed off peacefully. So much so that Lord Provost Samuel Chisholm was moved to issue a message on the final day praising the Exhibition’s “unexampled success” and expressing his “warmest appreciation” of “the splendid order, decorum and mutual courtesy which have prevailed on the part of the vast crowds of eager visitors”.

That last bit, by the way, was printed in capital letters and under-lined.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here