THE relentless march of the eco-warriors’ army is threatening to trample agriculture underfoot. For millennia, Scotland’s farmers have been the guardians of the countryside. We have a rural landscape that is both attractive and productive thanks to generations of farmers. We have a history and tradition of protecting the environment and ecology, sustaining wildlife and nurturing biodiversity.

Yet Scotland’s farmers face unprecedented challenges against a background of a regulatory regime that is driven by environmental puritans who have little understanding of, or sympathy for, the farmers of today.

Our farmers are caught in the middle of a political ‘fan dance’ where on the one hand there is rising global demand for food, while on the other, the tools that would enable them to increase food production are either being denied or withdrawn.

By 2050, food demand will have doubled as the world population increases by an additional two billion people. An extra 6 million people are born every month. Climate change is becoming a source of significant additional risks for agriculture and food systems and increasing water stress around the world means we'll soon have to do more with less.

READ MORE STRUAN STEVENSON: Scotland’s farmers are facing a Covid-19 Brexit breakdown

But the reality is that global food production is declining rather than expanding. The world is losing an agriculturally productive area the size of the Ukraine (250 million hectares) each year due to climate change and spreading desertification. So how can we close the circle?

According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation & Development (OECD), food prices will continue to rise by as much as 20% to 30% over the next decade. Food prices are literally a matter of life or death for more than a billion people in the world today. They spend 80% to 90% of their income on food. Even a tiny increase in the price of bread or rice means their family will go hungry.

There were major hunger riots in India triggered by the global rise in food prices in 2007/2008. More recently, food riots occurred in Venezuela in 2016 after the steep fall in oil prices and a collapse in the country’s economy. There are daily hunger protests in Iran where a combination of corruption and incompetence has brought that once rich nation to its knees.

Two-thirds of developing countries are net food importers and are extremely vulnerable to volatile world food prices. Of the billion people suffering from hunger today, about 850 million live in developing countries, the very countries expected to be most affected by climate change.

At the same time diets are changing radically in nations such as China, India, Brazil and Russia, where economic growth has boosted meat consumption. Unsurprisingly, farmers are following this trend by making the switch from grain to livestock to meet this intense market shift in demand.

Of course, calorie for calorie, you need more grain if you eat it transformed into meat than you do if you eat it turned into bread. You need three kilos of grain to produce a kilo of pork and eight to produce a kilo of beef. As a result, farmers now feed 250 million more tons of grain to their animals than they did twenty years ago. This in turn has caused a crunch in global grain stocks.

The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has predicted that, over the next 100 years, a one-metre rise in sea levels would flood almost a third of the world's crop-growing land. Add to this the use of productive farmland to grow biofuels and the conversion of corn into bio-ethanol in the US, where they say the amount of maize required to fill the tank of a family saloon would feed a human being for a year and you begin to see the impact that climate change is having on farming globally.

READ MORE STRUAN STEVENSON: In praise of fish farms

Scotland’s farmers are well placed to provide solutions to many of these global problems. We have the land, we have the resources, we have the capacity and we have the scientific know-how to help us feed ourselves and feed the world.

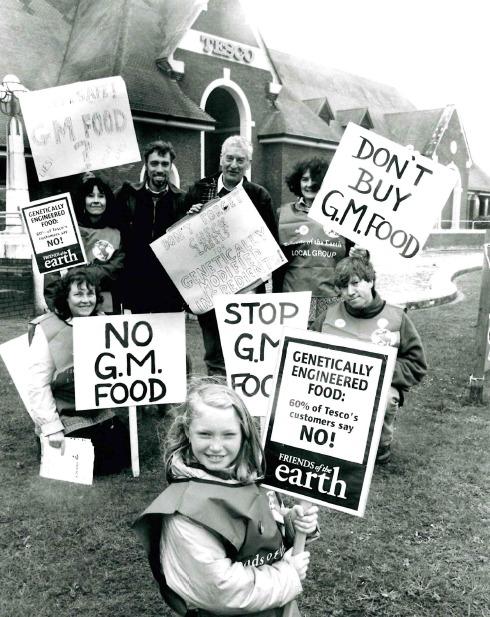

The one thing we don’t have is the political will. Instead of helping our primary producers to thrive, we place endless regulatory burdens in their way. For example, instead of developing GM technology, we have driven it out. We readily accept the need to have a genetically engineered Covid vaccine shoved into our arms, but we refuse to allow GM food to be shoved into our livestock.

Biotechnology will help to overcome the global shortage of grain and to counter the hunger riots in developing countries. GM foods offer a potential way out of this looming crisis, but the tabloid press and their ‘Frankenstein Food’ headlines and the Greens, have scared us into a zero-tolerance response, without due cause, across the nation and indeed across the whole EU. Tens of millions of hectares of GM crops are being grown successfully around the world, mostly using technology developed by European scientists who have been driven into exile.

Genetically modified insect and disease resistant crops reduce the number of pesticide and herbicide applications. Herbicide resistance permits direct drilling of the seed thus reducing the cultivation required and the consequent consumption of fuel.

READ MORE STRUAN STEVENSON: Living in the shadows of wind farm turbine tyrants

Biotechnology also provides higher crop yields without the requirement for additional farmland and enables crops to be grown in marginal areas such as saline soils, soils poor in nutrients and drought affected regions.

But instead of embracing biotechnology we deny our farmers access to its benefits, while handing a key commercial advantage to our direct competitors outside the UK.

Our policy in respect of GMs needs to be radically overhauled. We need to accept that scientific advances in biotechnology offer a way to alleviate hunger in the poorest nations while at the same time reducing costs for our own food producers.

If we are to secure a sustainable future for Scotland’s agricultural sector then we must give a high priority to protecting the interests of those who live and work in our rural areas. Only by so doing, can we hope to lead the world in producing high quality food in a healthy environment and a beautiful countryside while at the same time ensuring the future security of food supply to our citizens.

Our columns are a platform for writers to express their opinions. They do not necessarily represent the views of The Herald.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel