Richard Purden

KLAUS Voormann first heard rock 'n’ roll being thrashed out by a five-piece group of leather-clad Liverpudlians in Hamburg in October, 1960. In a feral atmosphere of drunks, sailors and sex workers, where violence often erupted, the 22-year old was on edge when he entered a basement club in the city’s red-light district.

He was soon drawn to a charismatic, mouthy frontman underneath a greasy quiff. “He was a cocky rocker,” says Voormann of the first time he spoke to John Lennon. “From then on it was like a world on fire. It was about art, movies, music. They were so open and it was difficult for us being German to understand. They would easily talk about their inner feelings. That was new to us. We were taking purple hearts [Dexamyl]) and talking so much it was unbelievable.”

A decade later, Lennon would sing about his most traumatic experiences on Plastic Ono Band and asked Klaus to join the sessions on bass. Newly unearthed out-takes and jam sessions have been released on a 50th-anniversary box set by Lennon’s estate. Voormann says it was “very emotional” hearing the exchanges between them for the first time. “I forgot so much about these sessions and hearing these talks with John, Yoko, Ringo and myself. I thought the time had gone much quicker between takes.”

Voormann arrived at Abbey Road Studios after a three-year stint playing bass for Manfred Mann joining Lennon, Yoko Ono, Ringo Starr and co-producer Phil Spector. Ringo struggled with a change in his old bandmate after Lennon underwent primal scream therapy.

“[Ringo] was a little upset at first. It wasn’t the same type of work he did in The Beatles. John and Yoko were so together that Ringo was a little sad. Ringo hadn’t known a relationship the way John and Yoko were, he would be more used to [John in] a more macho relationship.”

The death of Lennon’s mother, after being knocked down by an off-duty policeman when he was 17, and his absent father were among the cathartic themes on this often austere first post-Beatles collection.

“The subject wasn’t new to me”, says Klaus of Mother and the unsettling album closer My Mummy’s Dead, sung to the tune of Three Blind Mice. “I knew about most of those things from talks we had. The song [Mother] was so strong. He tried to portray his hurt and the way he was left alone. John was able with a few words to pin down a certain situation”.

Lennon would also voice his contempt of the British class system on the equally stark Working Class Hero featuring Lennon singing while strumming an acoustic. The track has often led some to dissect Lennon’s social background, perhaps missing the point. “John knew what it was like to be a working-class man," says Voormann. “Of course he had a better life than a lot of people but there were a lot of people without much money who had a hard life in Liverpool. He knew about those type of people and he had the right to write about them.”

Before working with Lennon, Voormann had already begun work on George Harrison’s triple long-player All Things Must Pass, ranked by many as the greatest solo album by any Beatle. Harrison’s song-bank stretched as far back as 1966 and would include tracks rejected by Lennon and McCartney.

“George would come into the studio with little joss sticks, he would light a candle and dim the lights, it was like a little altar. He would take much more time to record. The Beatles were never mentioned, it was time to turn the page and move on.”

As well as continuing to record on many of the Beatles' solo albums, including releases by Ringo, Klaus would be invited to play on some of the most definitive long-players and singles of the 1970s. The distinctive bass intro on Carly Simon’s You’re So Vain, featuring Mick Jagger on backing vocals, also appears on the 83-year-old’s impressive CV. As does Harry Nilsson’s definitive version of Without You.

“It was like a snowball effect once I played for John and George and I couldn’t have been happier. I worked with Carly Simon and Lou Reed, it was such a nice selection of people that asked me to play. All the people I played for I had fun with. Lou Reed was fantastic and such a lovely person. He was great. He was underrated. This project with Bowie and Mick Ronson [Transformer] was a well-done record and Lou had such great songs. Walk On The Wild Side is not me playing but I loved it. He and Bowie got on well and they were always laughing and having fun.”

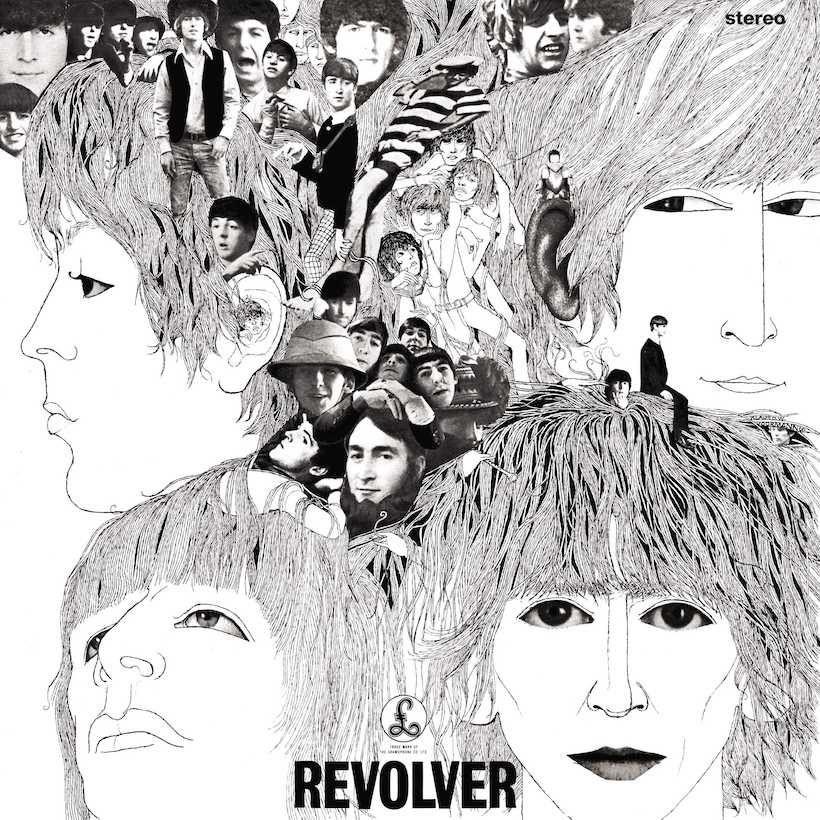

Outside the studio, Voormann has enjoyed a separate career as an artist designing album sleeves which would win him a Grammy Award for his most definitive cover, The Beatles' Revolver. “John called me and I went down to the studio and listened to the tracks. I was amazed. When I heard Tomorrow Never Knows I thought about all these little Beatles fans from She Loves You. Suddenly you have all these backward tapes at double speed with backwards symbols, sounds of birds. It was a hard job because you have to cater for the young fans and the people who are going to like this new stuff. In the end, that’s what I did with the portraits of the boys with lots of hair.”

Since that lively introduction in Hamburg back in 1960, Voormann continued to enjoy a remarkable insider’s perspective, even living with George and Ringo in London and later with George at his Friar’s Park mansion in Henley-on-Thames.

He would continue to work with Lennon in 1971 on the Imagine album. While the media and public had struggled with the blunt nature of Lennon’s debut they would be somewhat appeased with the more commercial-sounding Imagine. “It had to be a hit. I knew this was going to be an important and successful song,” says Voormann of the album’s title track. “It’s so direct. It was so simple and I loved the way he was able to use words and the way he was able to say so much. Every word helps and gives you hope.”

While Lennon was happy to draw a line on his musical past, it didn’t stop others trying to get his old band back together. Voormann remembers visiting Lennon in his New York apartment during a five-year break from the industry. “I was with John in his apartment when Leonard Bernstein called, who also lived in the Dakota building. He wanted John to get The Beatles back together for a UNICEF and United Nations concert.

"John told him off and really wasn’t very nice about it. He said: ‘I’m not getting The Beatles back together.’ He was happy not to be in the limelight.”

Klaus has remained in touch with Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr, both appeared on Voormann’s solo debut in 2009, A Sideman’s Journey. “Lately I visited Ringo and nothing has changed. He’s the same person. He’s had some hard times with cocaine and all that crap, I went out the picture during that, there was too much of this and that but he came back from it and doesn’t drink now either. He eats well, the same as Paul. When we are together it is always great. When Paul plays a concert close by in Germany he looks after me and Ringo does the same.”

John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band - The Ultimate Collection is out now

Mop top

The band’s mop-top haircut is attributed to Astrid Kirchherr who along with Voormann and Jürgen Vollmer befriended the band in Hamburg. She has rejected the notion, pointing to the haircut’s popularity in Germany and a French influence on the Hamburg trio’s style. Voormann suggests the Hamburg influence on the band aesthetic is most visible on the Beatles' For Sale album cover while baulking at their silver suit years preceding 1964. “Those silly suits. They looked terrible. I thought: ‘What crap are they wearing now’.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here