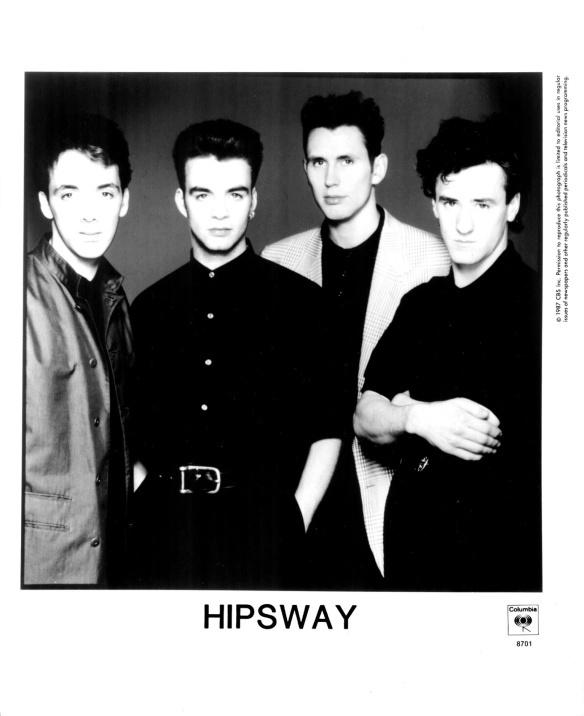

GRAHAME Skinner of Hipsway is unique. For in 40 years as a rock journalist, I can’t think of anyone else who has ever compared becoming part of the Scottish music scene to joining the Mafia. But the singer can back up his seemingly outlandish claim.

In 1984, he pulled pints behind the bar of the Rock Garden … then, the trendy go-to venue for every aspiring musician in Glasgow. It proved the perfect vantage point from which to plan his next move creatively.

“Somehow, I found my way to the Rock Garden, and it felt like that scene in Martin Scorsese’s classic gangster movie, Goodfellas, when Henry Hill starts working for the Mafia,” he recalled.

“I got to know all the people who were hanging out there, like Altered Images, The Bluebells, Del Amitri, Friends Again and James King.

“There was always something going on … a party, a band playing, a new exhibition or a club opening. There was a constant vibe in the bar. It was a creatively inspiring place to be a part of.

“So working there, I became almost like a ‘made man’ … in the very same way as Ray Liotta’s character in the film.

“Just being there was like getting a foot into the music industry itself.”

Skinner first dipped his toe into the water musically with drummer Harry Travers, a friend he’d met while studying at Strathclyde University.

They formed a short-lived band called The Very Essence Of Kites, who gigged with Lloyd Cole and The Suede Crocodiles.

“The name was inspired by the 1967 hit, Kites, by Simon Dupree and the Big Sound,” he revealed.

“It was covered by The Associates. We loved the sound and scope of the song. It was what we were aspiring to.

“I also remember Friends Again coming into the Rock Garden and asking us to play their new demo behind the bar.

“It was so good, I thought: ‘Oh, my God, this is the level we’ve got to try to reach. That suddenly set the bar a bit higher.”

Skinner spent a period fronting The Jazzateers and later joined The White Savages. But his next move would prove decisive when he met Johnny McElhone, a founder member of Altered Images.

The Glasgow group had been championed by DJ, John Peel and also supported Siouxsie And The Banshees and U2 on their UK tours.

They scored three hit albums, plus a string of Top 40 singles, including Happy Birthday, I Could Be Happy and Don’t Talk To Me About Love.

When they split in 1983, McElhone joined forces with Skinner and Travers to form Hipsway. They spent the next 12 months rehearsing and writing songs. The location chosen could not have been more mythical.

“We rehearsed in the dressing room of the legendary Glasgow Apollo,” recalled Grahame. I went to one of my first gigs there, The Stranglers, and also saw Elvis Costello, Eddie And The Hot Rods, Squeeze and Eric Clapton play the venue.

“We’d walk in the front door and down through the empty theatre, and find old concert tickets lying on the floor.

“The place was like my church. Inevitably, the ghosts would start seeping out of the walls. But rehearsing in the Apollo dressing room was the closest I ever got to actually playing there.”

James Grant, of Friends Again and later, Love And Money, played guitar on Hipsway’s first demos – Broken Years and Forbidden – two songs which became cornerstones of the album.

Ally McLeod of Modern Man also played guitar on the early sessions.

“Our influences were Talking Heads – who were quite funky and dance-y – and Talk Talk, particularly their album, The Colour Of Spring,” says Grahame.

“Johnny would play a riff, Harry would join in on drums and the guitarist would try to figure out something to go around that. Harry was really important to the lyrics. We’d both sit in his bedroom late into the night – drinking wine – and come up with words.

“He was the real driver of that, while I was more of a melody guy. But I’d add bits in or edit and try to shape the songs.”

The band signed a deal with Phonogram Records, who immediately booked them into Ridge Farm Studio in West Sussex with producer Gary Langan, a founder member of The Art Of Noise. Pim Jones joined the band as permanent guitarist.

“Gary was a real happening guy at the time, so we wanted to work with him,” said Grahame.

“One of the first songs we recorded was Ask The Lord. James Grant came down to sing some backing vocals on the track. Gary kept asking him to do his part again and again. I remember him saying: ‘It just hasn’t got that X-factor’.

“James was going: ‘What the f*** is an X-factor?’ “None of us had ever heard the expression before.

“But his experience was invaluable. The earliest version of The Broken Years had two verses, which were exactly the same.

“Gary said: ‘I think the song would sound better if we cut a bit out’. He was real old school, so he just marked it on the tape, got a razor blade and sliced through it. We were thinking, what is he doing? But when he stuck it back together again, it sounded brilliant. He’d got us to the important bit of the song so much faster. So that was a real early lesson for us.”

Midway through the recordings, Langan moved on to another project, and producer Paul Staveley O’Duffy was drafted in to finish off the album.

He’d engineered records by Marvin Gaye and Yes and would later work with Swing Out Sister, John Barry and Amy Winehouse.

“Paul was a soul guy and really knew his stuff,” recalled Grahame.

“He didn’t look the part … he was like a member of Bon Jovi, with his good looks and long hair.

“Gary had been a bit more laissez faire. He was great, and I don’t want to sound disparaging, but he was much more rock ’n’ roll, let’s put it that way.

“Paul was business-like and structured. So he took what we already had and polished it up. He had the soulful sound we needed.”

The album made an immediate impact thanks to the chart success of debut single, The Honeythief, and key songs such as Tinder, Long White Car and Set This Day Apart. More importantly, on a personal level, it was also the record in which Skinner found his true voice.

“It was the first album I’d made, when I was really trying to be me,” he said.

“When I recorded with The Jazzateers, I wasn’t using my own voice – I was trying to be Iggy Pop or Lou Reed. I wasn’t being myself.

“Making a record can be quite difficult emotionally, especially when you’re so young and don’t fully understand things. I was learning on the job.

“Johnny had already made three albums, so he knew what he was doing. But it was different for me. At times, it was all a bit of a mystery. I felt powerless in the whole process.

“Whereas now, I can have ideas, be the co-producer and have some real authority.”

This summer, indie label, Past Night In Glasgow, plan to re-release Hipsway on vinyl for a new generation of music fans.

Grahame said finally: “When I listen to the album today, I like it much more than I did at the time. I don’t know why that is. Maybe I can just appreciate it more.

“It was a high point for me both commercially and artistically. It still holds up as a piece of work. I’m proud of everything I’ve ever done. I’ve made a lot of records, and they’ve all been very different. I’m proud of that too. I never repeated the formula. But now, I can see just how good an album Hipsway was. It stands the test of time.”

THE Billy Sloan Show is on BBC Radio Scotland every Saturday at 10pm.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here