It was a once-thriving community which was swept away by an aristocrat’s whim and then buried by the march of progress.

But now archaeologists who excavated the ‘lost village' of Netherton say its inhabitants may have put their trust in an ancient talisman to protect them from harm - after making a startling and mysterious find in the remains of one of the settlement’s ruined buildings.

The village of Netherton was uncovered in North Lanarkshire during work to upgrade the M8, M73 and M74 Improvements.

Thought to have been settled sometime in the 14th century – placing it in the medieval period - the village was inhabited until the 1700s when it was demolished by the Dukes of Hamilton as they transformed their estate into well-ordered and symmetrical parkland with wide avenues and enclosures.

What remained of the village was then destroyed with the construction of the motorway – save for the remains of four houses right on the hard shoulder.

The remains of four homes were found next to the motorway

An excavation of these ruins was carried out in 2016 by experts from GUARD Archaeology, and the final report has now revealed a mysterious find totally out of place with the rest of the site.

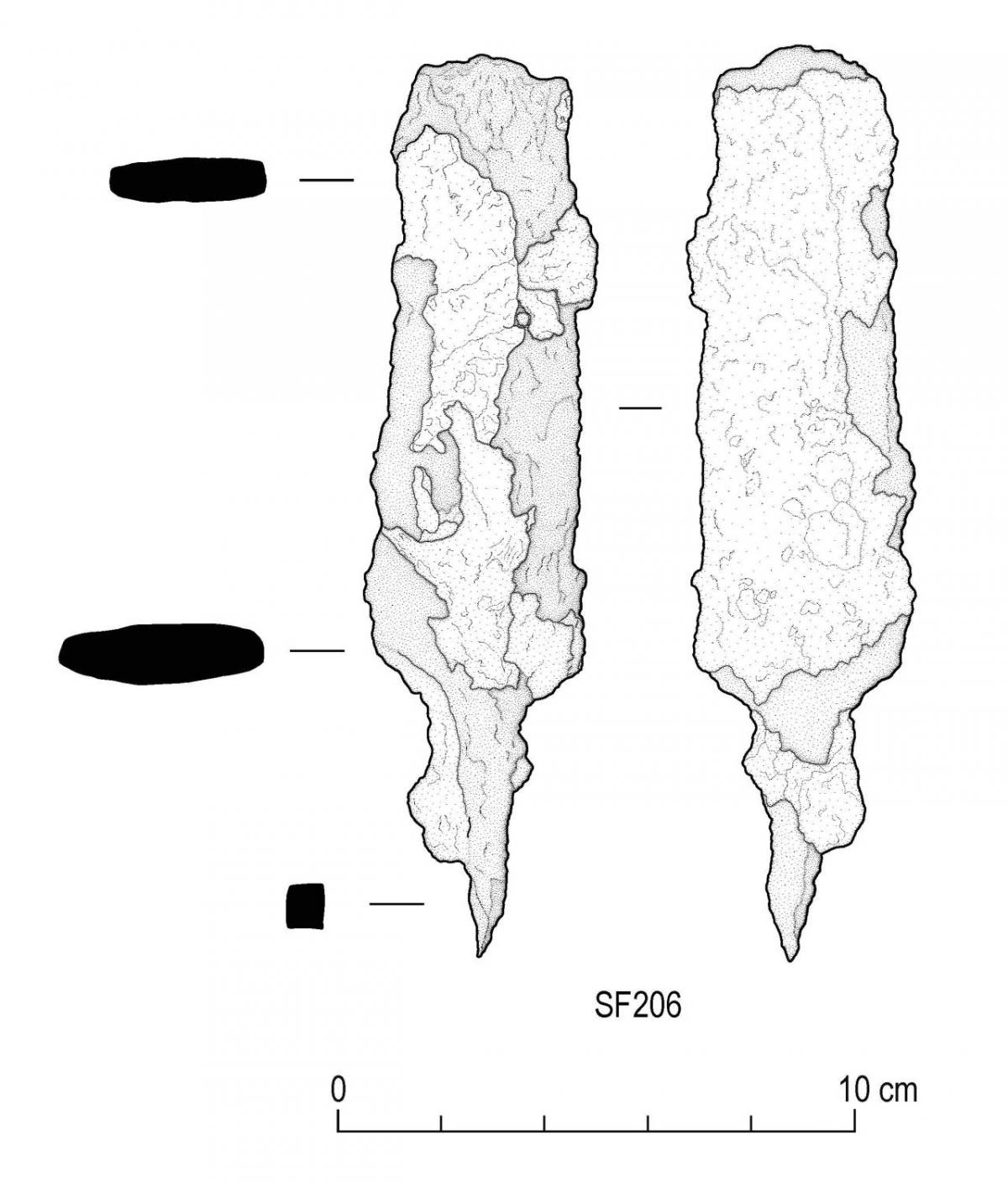

Underneath one of the buildings, in amongst the foundations, was a dagger which dates back 2,000 years to the Iron Age.

The blade, buried in its sheathe and likely still useable when it was deposited, was found alongside other items - a whetstone of fine-grained sandstone, a spindle whorl made of cannel coal, a possible gaming piece made from green glaze pottery, and two seventeenth century coins - which date to the time the house was built.

READ MORE: Most detailed maps of Culloden ever created mark anniversary

It is thought the weapon was intentionally laid down as a good luck charm in the belief its ancient magic would keep the inhabitants safe from harm.

“Mineralised organic material on its blade suggests it was sheathed when buried, and that it was probably intact and still useable at that time,’ said Gemma Cruickshanks of National Museums Scotland, who analysed the metalwork. “The form of this dagger is indistinguishable from Iron Age examples, indicating this simple dagger form had a very long history.”

An artist's impressiom of how the village may have looked

The practice of depositing special objects in medieval and post-medieval buildings is well documented and was a ritual performed to protect the building and its inhabitants.

In this case, the archaeologists believe the dagger’s “potential antiquity as a prehistoric object” perhaps lent it a quality of ‘otherness.’”

Reuse of prehistoric objects as depositions in medieval settings has been recorded in excavations of churches in England, and flint arrowheads were traditionally identified as ‘elf-bolts’ and long recognised for their malevolent magical properties.

“The special or talismanic qualities of this dagger as a protective object may have enhanced the ritual act to protect the household from worldly and magical harm,” said Natasha Ferguson, another of the report’s co-authors.

“The deposition of these objects under the foundation level of one of the houses may have been intended to affirm this space as a place of safety for them and generations to come.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel