FOR nearly a decade, Levon Biss has been journeying into the smallness of things. Using strobe lighting, high-end macro lenses and a specially-designed rack which moves his camera by increments of microns rather than millimetres, the London photographer has produced bodies of work such as Microsculpture, an extraordinary series of insect close-ups so rich in detail they can be displayed as huge, wall-mounted prints.

When a 2019 touring exhibition of those images set down at the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh (RBGE), a chance encounter with herbarium curators David Harris and Lesley Scott set up the opportunity for a new project. And so was born The Hidden Beauty Of Seeds And Fruits, macro-photographic prints of 59 specimens chosen from the garden’s massive collection. Completed just before the first lockdown in March 2020, it took the 45-year-old weeks of painstaking work.

The branch of botany concerned with seeds and fruits is carpology. RBGE’s herbarium contains more than three million specimens of dried plants and 3500 carpological specimens, collected over three centuries and on every continent. A project born out of the Enlightenment finds 21st century expression in the cutting edge work undertaken by the garden’s botanist charting climate change and plant migration, or measuring pollution levels. In that context, Biss’s detailed images are more than just eye candy for visitors and more than just art works drawn from the natural world.

“I don’t classify myself as an artist,” he says. “I prefer to use my work as a communication tool. I use a creative medium but I use that as a tool to communicate to people. All these specimens would never normally be seen by the public. They’d be locked in drawers. So I try to open up these collections so that the museums can educate the public about their collections. I think art is a wishy-washy thing. I’d rather have my photography used for a proper purpose.”

With so many specimens, how did he make his selection? “We went through thousands of boxes and looked at untold numbers of specimens. I was looking first of all at the appearance. Are they interesting visually? That’s how it always starts. Is it going to make a good photograph? Then you look at the preservation, what kind of condition is it in? There’s no point in showing people an old specimen that looks decayed and horrible. On top of that I was looking for an interesting story. A lot of these specimens were collected a long time ago. Some are 100-plus years old, and I often wondered under what circumstances they were collected. Who collected them? What did they have to go through to bring this specimen from the other side of the world?”

Many had faded notes attached in exquisite copperplate handwriting giving the specimen’s botanical name. One or two even had descriptions of where the specimen was discovered. “I found those quite romantic, those 100-year-old notes. There was one where the botanist had written that he found it in ‘a wholly unremarkable landscape’. I had this vision of this guy traipsing through a jungle for weeks, depressed and tired and hungry, and that was the most he could come up with for a description.”

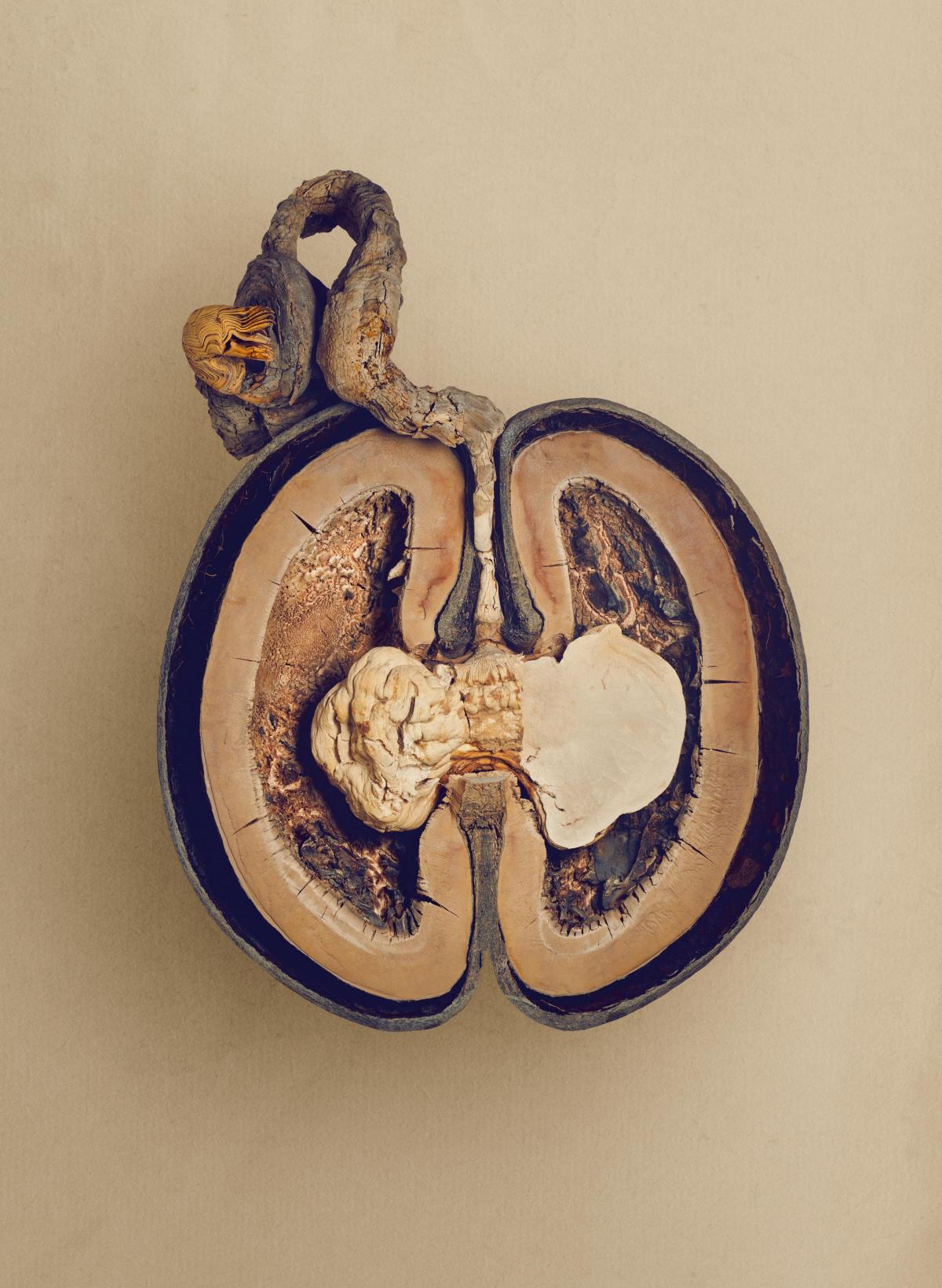

Included in the exhibition and a corresponding book are images of seeds such as the heart-shaped Yellow Piquia, the exquisitely creepy Bofiyu (which appears to have a set of eyes peering out from within it) and the Rosary Pea. Its bright red and black seeds look like Ladybirds nesting in a handful of wood shavings but are highly toxic to the point of being potentially fatal. That hasn’t stopped them being used as ornamental beads and, after being boiled and treated, as a treatment for arthritis.

Other seeds and fruits in the exhibition resemble (variously) aliens, insects, Hallowe’en masks, items of avant-garde costume jewellery, internal organs and – in the case of the Australian Burbark – that spiky graphic you see being used to illustrate news reports about coronavirus. The names are equally fantastic: Cow Itch, Grapple Plant, Coco De Mer, Dutchman’s Pipe, Resurrection Plant, Monkey Egg and Black She-Oak are just a few of the outlandish monikers.

Biss creates his images using a process called photo stacking in which multiple images are taken and then layered, or composited in photographers’ jargon. “You do that to achieve full focus because the higher the magnification, the less there is in focus,” he explains. “It’s what you call a shallow depth of field. So there will only be a tiny sliver of focus within the image.” Biss’s insect photos used 10,000 separate images and took months to composite. With time against him in Edinburgh, typically he shot only 100 or so images of each seed, his camera moving forward by 10 microns at a time so the composited final image is always razor sharp.

Does he have a favourite? He does. It’s the wonderfully named Electric Shock Plant, which is native to Brazil and Argentina and is covered in tiny hairs which deposit calcium phosphate and other noxious minerals in the mouths of any herbivore rash enough to try to eat it. The result is a feeling a bit like an electric shock. “I had to insist quite hard to the herbarium curators that we use the local names for things because for me, if you use a scientific name, which is in Latin, it’s just a jumble of words,” he says. “But something called an Electric Shock Plant is fantastic – if you’re trying to educate people you have to meet them halfway.”

Not for nothing do we talk about the seeds of knowledge.

The Hidden Beauty Of Seeds & Fruits is at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh until September 26 (entrance free); The Hidden Beauty Of Seeds & Fruits: The Botanical Photography Of Levon Biss is out now (Abrams, £30)

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here