Fire Engines. Lubricate Your Living Room. Released – 1981.

IT could be argued that the only conventional thing about Fire Engines’ debut album was that it was pressed on a circular piece of 12-inch black vinyl with a hole in the middle.

Everything else concerning Lubricate Your Living Room presents a challenge to record buyers, both visually and audibly.

When asked by the NME to sum it up on release in 1981, frontman Davy Henderson was almost dismissive, saying:

“It’s not actual songs. It’s something else we do, not some big important thing. It’s just a record to be f***** played.

“It’s not like it’s our first LP and we mean this kind of thing. It’s an amalgam between Pop:Aural and Codex Communications using Fire Engines. And it’s brilliant.”

The singer was right … it was brilliant. But he got it wrong with his assertion the record was not important.

Lubricate Your Living Room felt like a door being kicked open. It still does.

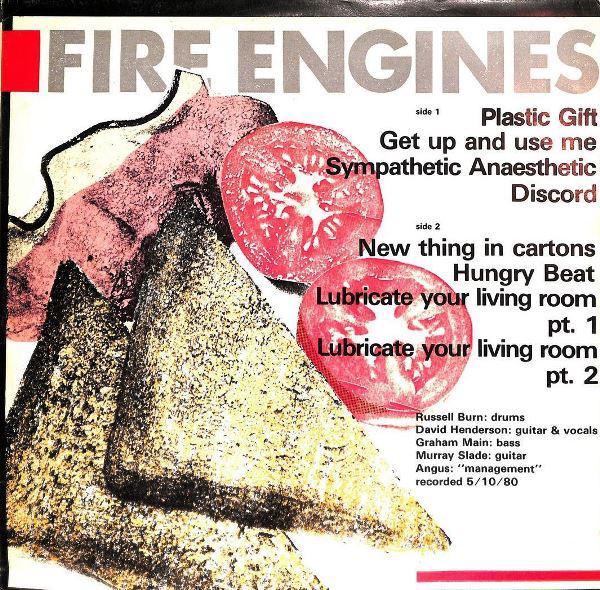

Over eight mainly instrumental tracks, the Edinburgh band – Henderson, Murray Slade (guitar), Graham Main (bass) and Russell Burn (drums) – had a sound that was jarring and confrontational.

On the few places lyrics are used I’ve no idea what Henderson is singing about. It’s virtually impossible to pick out actual words or phrases.

They were inspired by one now-legendary gig in the capital.

“On May 7, 1977, I went to the White Riot Tour at The Playhouse,” said Davy.

“It had an amazing bill of The Slits, The Subway Sect, Buzzcocks, The Jam and The Clash. Some of them were the same age as us. It was a real Year Zero moment.”

Slade feels the same way. He said: “It was a brilliant gig with an energy which has never been matched.

“It had such a huge impact because they were demonstrating you didn’t have to be some kind of 1970s virtuoso on guitar to be in a band. It convinced me you could do it.”

Henderson was a friend of Robert King of The Scars, whose first single, Adult/ery/Horrorshow was being released on Fast Product.

The indie label – launched from a flat in Keir Street by Bob Last in 1978 – made records with The Mekons, The Human League and Gang Of Four.

“Lots of young people would hang out. I spent my weekends there,” said Davy.

“It was unbelievable to think somebody you’d just met had a label and was putting out great records.

“Bob used them as a kind of focus group. He was probably the first artist I’d ever met. But he was using the medium of music to put his ideas across. And that was a total gas.”

Henderson, Main and Burn were members of The Dirty Reds, whose singer, Tam Dean Burn – the latter’s brother – is now a successful actor. While Slade played guitar with Station Six.

“We played a community hall in Cramond and the gig was significant because they crashed our set and borrowed instruments to play a few songs,” said Murray.

“I later met their manager Angus Groovy who told me Tam was leaving. They were putting a new band together and wanted me to join.”

Fire Engines formed in 1978, and practised in a bedroom in Slade’s family home.

“The only stipulation was that Murray wasn’t allowed to play any barre chords. That was it,” revealed Davy.

“The tempos depended on how much adrenalin was coursing through Russell.”

The band’s name was a joint effort.

“When I was six years old, I’d written a small poem at school called Fir Ingins. I couldn’t spell it correctly,” revealed Murray.

“We also liked the song Fire Engine by The 13th Floor Elevators. So it all came together from that.

“And it wasn’t THE Fire Engines. Just, Fire Engines. Angus always said ‘The’ is so boring. So that’s how we got the name.”

Their influences included Richard Hell and the Voidoids, Lydia Lunch and James Chance and the Contortions. But musically, there was no grand plan.

“We were into more riff-ier stuff which was quite direct and simple. That kind of jagged, abstract, faux white James Brown. Only we did it worse,” recalled Davy.

And Murray said: “The only plan was that it couldn’t be laid back. Thatcher was kicking about so there was a bit of anger around too.

“It had to be upbeat and in your face. It was more about energy.”

The band scraped £46 together and hired producer Wilf Smarties to make their first recording.

“The studio was the living room of his house in a very ordinary street in Fife. Wilf was plugged into that particular suburb,” said Davy.

“We played our entire set twice through. Until we listened back we’d never actually heard ourselves before. It was the first time I’d heard my voice and I immediately thought … f****** hell, that is brutal. Why is it not like For Your Pleasure by Roxy Music?”

Two songs – Get Up And Use Me and Everything’s Roses – were chosen as their 1980 debut single on Codex Communications, run by manager Groovy.

“We were in this massive flat which was freezing and didn’t have any money. The cats went feral,” revealed Davy.

“There was a one hundred weight bag of potatoes – which Angus’ old man had brought up – and they were all sprouting. There was no other food at all.

“But this massive box of records turned up. Because we were doing things so cheaply the single sleeve had to be folded up by us

“But seeing the record suddenly made it real. John Peel played it, which was unbelievable. Paul Morley gave us loads of credit in the NME and recommended us very highly.

Meanwhile, Last had moved on, forming another label Pop:Aural who released singles by The Flowers, Boots For Dancing and Restricted Code.

He wanted to make albums that challenged pop conventions.

“Bob had these ideas that music could be something other than the standard single, album, tour type thing,” recalled Murray.

“It was his suggestion to extend the riffs and tracks we already had by putting bits and pieces on them, and to miss out vocals.

“So you had a music you could stick on and not have to sit down and analyse. You could either dance to it or, ideally, put it on and do your housework, whether that was sweeping the floor or painting the garden fence. Just ACTIVE background music rather than more laid back muzak.”

Tracks such as Plastic Gift, Sympathetic Anaesthetic, Discord and Hungry Beat sounded like nothing before, or since, on the Scottish music scene.

“Bob wanted to create a series of exciting, ambient records,” revealed Davy.

“He was asking us to be the medium for this idea which was really appealing. It was the total opposite of making a definitive album of your first set of songs.

“The way we saw it was that this was not really a Fire Engines’ record, it was Bob’s record for Pop:Aural in which he was using our set to communicate his ideas.”

One reviewer said: “It sounded like nothing else. Fire Engines were then occupying a completely different hemisphere to that of their contemporaries.”

While it date-stamped a frenetic creative period, Slade admits to having mixed feelings about the album now.

“I am proud of it … there’s not much else like it,” he said.

“But I’d have liked our first LP to have been much more conventional by having actual songs on it.

“I don’t sit down and listen to it. I might put it on if I’m doing something around the house. Personally, I don’t think it stands up to scrutiny if you listen to it too hard. You inevitably pick holes in it. But self-criticism is important.

“I’m now an architect, and when you design things you can never be one hundred per cent satisfied. There comes a point where you’ve got to get it out of the door. To be sure that it’s perfect in every way is an impossible place to be. I wouldn’t ever attempt to make a record on that basis.

“So it was perfect in that it represented us at that particular time.”

And Davy added: “It’s definitely NOT our definitive record. In 2006 when we discovered we still had the Wilf Smarties’ tapes it was quite valid to say to Domino Records … put this out. It’s what we regard as Fire Engines not Lubricate Your Living Room. It was more of a Pop:Aural concept album.”

* THE Billy Sloan Show is on BBC Radio Scotland every Saturday at 10pm.

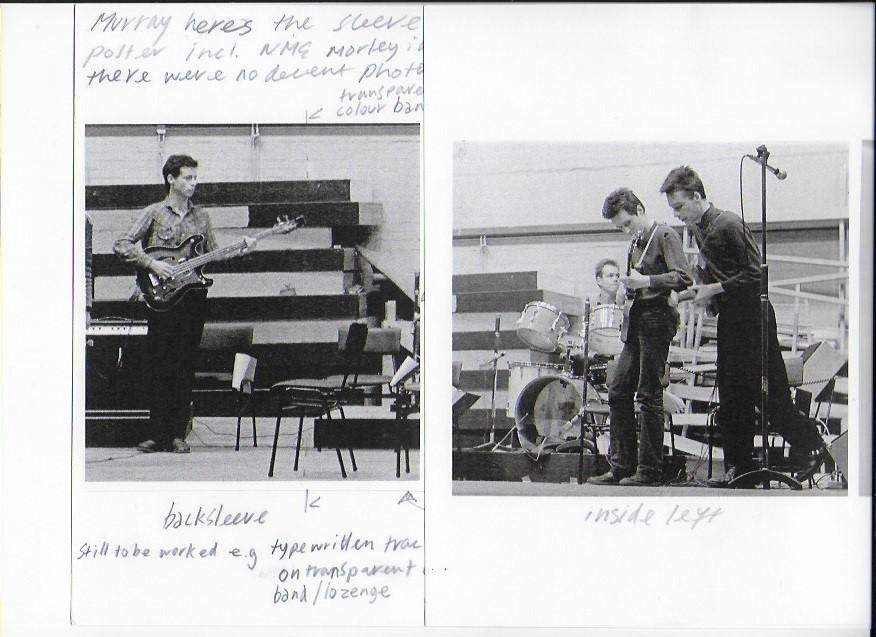

DESIGN CLASSIC

Lubricate Your Living Room looked great too.

The record was packaged in a sleeve that showed a picture of a rather meagre cooked breakfast.

“The artwork was pretty random. Who puts their breakfast on an album cover?” said Davy.

“The title came from a billposter which said ‘Lubricate your toilet with Flash’. We just switched it.”

While the band was turning the music scene on its head, Orange Juice were creating a revolution of their own in Glasgow.

They were signed to Alan Horne’s, Postcard Records, alongsde Josef K, Aztec Camera and The Go-Betweens.

Both bands played a show at The Mayfair in 1980, cited by Bobby Gillespie of Primal Scream as one of the gigs that changed his life.

Did Horne try to sign them?

“I can’t remember Alan actually saying ‘Let’s make a record,’” revealed Davy.

“But I do remember letting him hear our single, Candyskin. He just walked away laughing, saying, ‘My God’.

“We’d played with Orange Juice so often it was maybe implied, or assumed, we’d also be on Postcard.”

The band split after their third single, Big Gold Dream. Was it over too soon?

“It was a combination of factors. We’d always said if we didn’t come up with another song by a certain time we should think about splitting up,” recalled Murray.

“It was never a definite thing, but those words were said. I got a phone call from Russell on New Year’s Day, 1982, saying Davy had left. Bob Last dragged him away to form another band. I think he saw him as a source of lyrics, music and attitude he wasn’t getting with us.

“So, was there an element of a potential unfulfilled? I think so. If we’d been older we might have stuck together. It wasn’t a falling out of personalities, put it that way.”

In 2004, they reformed to play with The Magic Band and Franz Ferdinand. Their most recent gig was at Leith Theatre four years ago.

Could they give it one last whirl? It depends who you ask.

“No, William, I’m 60 now, man,” said Davy, laughing.

“The idea of getting up there and singing that I’m an idiot youth – a line from Get Up And Use Me – would be really difficult. I suppose it’s just the vanity of my age.”

But Murray said: “During rehearsals in 2004, Davy was really enjoying it and said: ‘Why did we split up?’ We all just looked at him.

“I think it might have definitely disappeared. But we still get on pretty well, so there’s always a chance.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here