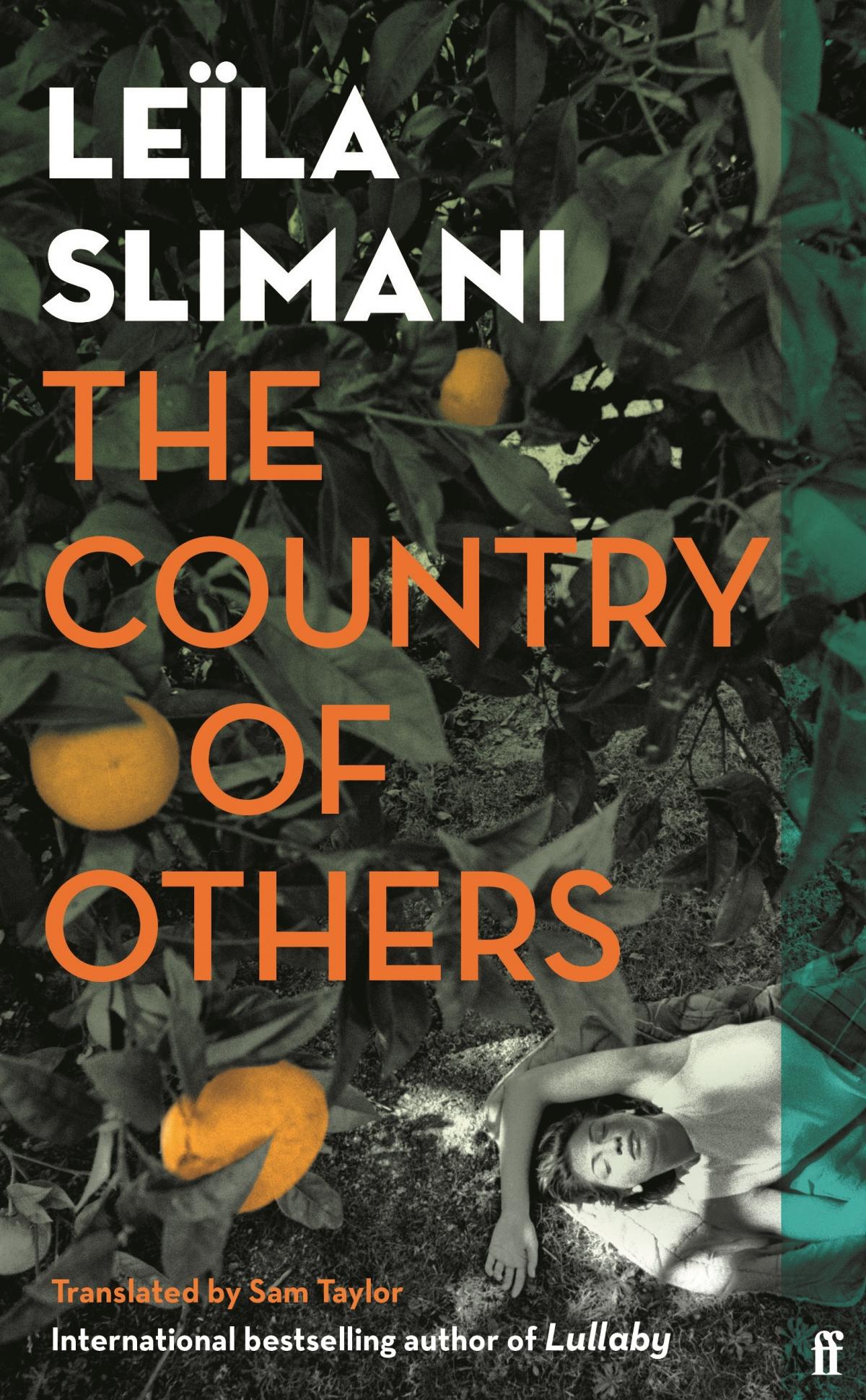

The Country of Others

Leila Slimani

Faber and Faber, £14.99

Review by Neil Mackay

Nazi planes are strafing towns in French Alsace as the Allies push Germany back over the Rhine in autumn 1944. Civilians cower in air-raid shelters, except for Mathilde – she has a different way of confronting death.

While her family hide in “bunkers and basements … huddled together like animals”, Mathilde hurries upstairs “not for her survival but to quench her desire”. At moments of intense fear, Mathilde’s instinct isn’t to run but experience orgasm in order to “gain some sort of power over the war”.

It’s a jarring, spellbinding, disturbingly Freudian introduction, by Leila Slimani in her latest novel The Country of Others, to a character – a force of nature – destined to become one of the great, flawed heroines of modern literature.

Young Mathilde is bored, even amid the terror of war. An exotic young Moroccan army officer, Amine Belhaj, is billeted in her town. Mathilde decides she doesn’t just want him – she can redefine her life through him. He represents adventure; she needs others to envy her daring. As war ends, Mathilde does the unthinkable – she marries Amine, packs her bags and leaves for Morocco.

In France, Amine was a hero who fought for the republic. In Morocco, he’s just another Arab, sneered at by French colonialists – labelled a “negro” because of his dark skin.

What does that make Mathilde? Is she still French? Is she Arab now? Mathilde walks along forbidden boundaries her whole life, damning the consequences. A consummate outsider, she’s delinquent, messy and mercurial – throbbing with the confusion of existence. At one moment, she’s bringing near destruction to the traditional Arab way of life – encouraging her hip sister-in-law to date sexy white boys and wear pencil skirts; the next, she’s wallowing in misogyny, metastasising the submission of women within Amine’s world and all but bowing to her husband. Amine beats Mathilde and worships her; Mathilde hates and desires Amine. In this novel, power and gender are never easily drawn, but stark, curdled and at times terrifying.

Amine himself is brought into a place of boundaries – a No Man’s Land – by Mathilde. What is he with such a wife? How can a real Arab man have married this woman – blonde, sexually free, taller than him?

What of the Belhaj family itself? Amine’s mother is an illiterate doormat, the family owns slaves from sub-Saharan Africa – yet Amine wants to live the life of a Westerner, creating his colonial-style farm, drinking in bars, socialising with the French. He’s a man in a permanent state of cognitive dissonance – simultaneously enjoying the gazes that fall on his wife, and horrified by her sexual allure. He both wants to be with Westerners and hates them for the sense of humiliation they raise inside him.

In the Belhaj home everyone struggles with their identity. What will their son become? A patriarch or a modern young man? Or their daughter? Unlike other young Arab girls, the French-Moroccan Aicha isn’t just educated, she’s brilliant. What lies ahead for her? We close the book on Aicha’s thoughts – the future chillingly glimpsed in the imagination of a troubled, scared, angry child.

Morocco itself is in a state of fatal identity crisis. As Mathilde and Amine arrive, the nation is about to convulse against French colonial rule. Amine’s brother is drawn into the conflict. The French would call him “terrorist”; many Moroccans, “freedom fighter”.

As the Belhaj family struggle to make sense of themselves, the violent uprising creeps closer to their farm – this strange oasis they’ve made for themselves where they can pretend to be both European and Arab at once; where Christmas is celebrated, and where women can be smart and entertaining, but where girls will also be married off to ugly old men if they step out of line.

Leila Slimani is a French-Moroccan writer and while it’s always foolish to look for the lives of authors in their work, it’s impossible not to feel the weight of an intimate relationship to recent history pouring from her onto the page.

There’s a beautiful brutality to The Country of Others. No character is going to carry you through this book as the voice of reason or the spirit of morality. Everyone is deeply, darkly flawed. The French are brutes, the Arabs are brutes; the French are victims, the Arabs are victims. Everyone is damned in a land which nobody truly owns because it’s occupied.

There are rich and unpleasant political lessons in the book for today – especially for Western minds. Mathilde is that unusual creature rarely thought of in Europe and America – a white foreigner. To the collective white Western mind, “foreigners” come from “over there” to “here”, they’ve different-coloured skin to us. If we’re kind, we’ll feel for their struggles to reach our shores and assimilate our culture; if we’re cruel, then we’ll hate them just for being here.

But what if we were the foreigner – what if whiteness and “Europeanness” made us the outsider? What if we were the ones trying to assimilate and understand an alien culture that at best pitied us and at worst hated us and wanted to kill us?

Slimani has written both an historical novel, in terms of its content, and a very contemporary novel, in terms of its themes. Her prose reflects that beautiful brutality which the book explores. She can hurt you and uplift you in a single paragraph: “He contemplated the indifference of nature and the stupidity of men. We will all kill one another, he thought, and the butterflies will continue to fly.”

As Cyril Connolly once wrote of F Scott Fitzgerald, Slimani’s style sings of hope, her message is despair.

Don’t come here looking for a complicated plot with twists and turns. This is family drama lifted to Nobel Prize winning heights. Slimani walks in the footsteps of a long line of great, empathetic writers. I found it impossible not to think of the work of John Steinbeck as I read her, particularly East of Eden.

Here’s why I know this is a great book, worthy of being read a century from now. I finished the novel a week ago, and I still pine for the characters – difficult, monstrous and glorious as they all are – and the sound of Slimani’s voice in my head. She has created a masterpiece.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here