Technological innovation is no new thing in Japan. It has been around for hundreds of years,

from the innovative resuse of fabrics to the development of the ceramic heritage. This exhibition, first seen at CHAT (Centre for Heritage, Arts and Textile) in Hong Kong in 2019, then further developed at Japan House in London earlier this year, celebrates the design studio Nuno, run by Designer Sudo Reiko.

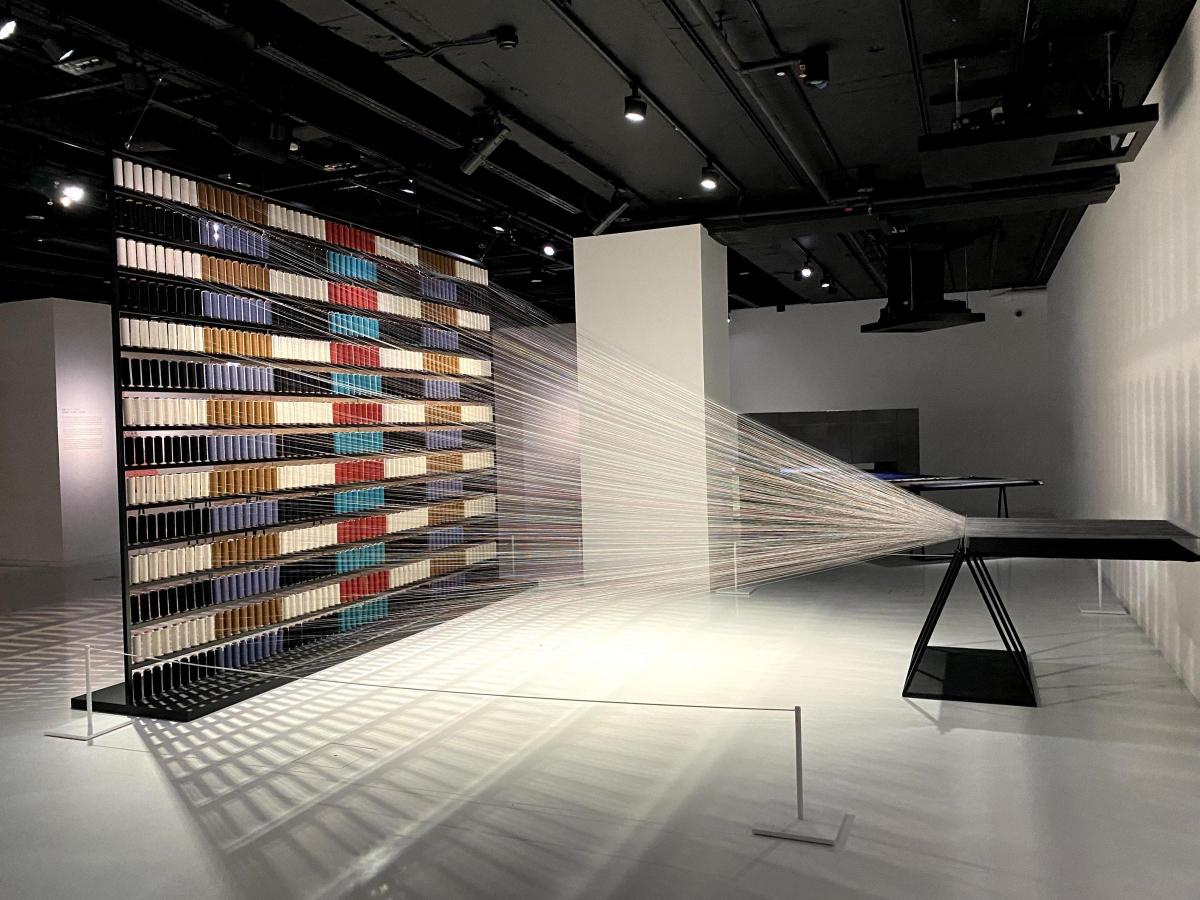

The set-up at Dovecot, Edinburgh’s tapestry studios, is a series of installations made by Tokyo-based designers Rhizomatiks, using fabric, sound and film to evoke the essence of making and innovation. In one corner, we have fabric made from the discarded outer layer of silk cocoons, Kibiso, its chequerboard-esque pattern laid out on a trestle, the raw materials laid out at the edge, the sound of an indeterminate machine – presumably to weave this material traditionally found too tough for the making of textiles – above.

Elsewhere, overhead projection shows a textile worker at Nakanishi Dye Works in the Kansai region, screen printing stitches in glue on to a fabric which is crinkled and heat shrunk, an innovative combination of polyvinyl alcohol, whose fibres are used in agricultural and industrial textile production, and thermoplastic polyester, layered and melded together. The techniques are fascinating, a marriage of technological innovation with centuries-old skills and a huge range of small textile factories and dye works whose heritage is strongly present in their work, yet who actively embrace new technologies.

Elsewhere, Japanese washi paper and amate bark cloth, the work of Otomi craftspeople in Mexico, are joined together in a cloth which makes homage to the contrasting qualities of both. It is fascinating and clinically innovative, at the same time.

This melding of traditions, of the old and the new, was the founding ethos of Nuno Fabrics, set up in 1984 in Kiryu in Gunma Prefecture, in the east of Japan. The current ethos is based on sustainability – of regional manufacturing, of materials and of craft skills. Sustainability, in another way, has long been part of Japanese textile tradition, as it has in many traditions worldwide. In northern Japan, from roughly the 1600s onwards, worn cotton fabrics, traded from other areas of Japan where the cotton plant thrived – unlike in the northern islands – would be revived by stitching them together in to new items with sashiko stitching (a running stitch, interlocking, often used to hold together a number of layers of fabric) and boro patching, each neatly done, creating hugely beautiful fabrics that were reused as clothing or futon covers.

Nuno recycles in a different way, perhaps in using materials which are the byproduct of modern manufacture, such as thermoplastics, alongside silk, hand-made washi (Japanese paper) and nylon tape. Craft traditions inform the new technologies used, including caustic burning, weaving and dying.

Whilst the fabrics themselves are fascinating and the installations inventive, the processes and ideas can seem obscured, dry – and the urge to touch these innovative fabrics to engage with them is overwhelming, thought strictly forbidden – and it is perhaps the films, made in textile factories in different parts of Japan, which are the most intriguing, invoking the human amongst the machine. Here is the cross-section of Japanese traditional skill and technological innovation. There are ancient-seeming looms here that have been mechanised, a snapshot of a recent past, but weavers and technicians are still required to cut threads, to man the machines, to monitor, to set up. In one instance, in a factory in Kyoto, a weaver laboriously, assiduously, cuts tiny threads across a roll of fabric in order to create a certain aesthetic effect of tiny frayed threads. The task looks Sisyphean, and it subtly raises too the question of what is and isn’t done by humans; of what should and shouldn’t be mechanised, of the human imprint on what might otherwise seem a process driven by machinery. There are a number of factories in Kyoto and elsewhere, each frequently in an old or industrial building, the machinery old yet immaculate, the floors clean. Some of it has a dystopian future look about it, the cement floors and spindly wheels whirring as thread is passed on to a loom.

The silk cocoons, too, as ever, are treated in a brutally industrial manner, run in rattling metal containers along a conveyor, plunged in boiling water, the silk thread skeining out, the cocoons pulled apart to make workable material.

Elsewhere, we see textile workers and weavers tending the huge looms and spindles, skilled workers engaging in different processes – it is fascinating stuff. These small factories exist in multiple locations across Japan, the films and the exhibition as a whole serving to underline the great living tradition of textile manufacture and innovation, and the long heritage behind the innovative fabrics produced.

Making Nuno: Japanese Textile Design Innovation from Sudo Reiko, Dovecot, 10 Infirmary Street, Edinburgh, 0131 550 3660, www.dovecotstudios.com , Until 8 Jan 2022, Mon-Sat, 10am-5pm, Adults £9.50, Concessions £8.50.

Critic's Choice

BRINGING a Hebridean view to the centre of Edinburgh this week, this Dundas Gallery group show of five contemporary artists from North Uist shows the draw of the island to an increasing population of artists, writers and musicians.

These five artists are all inspired by the natural surroundings on North Uist, the stuff of a land grown on 300 billion year old rock. Fergus Granville makes sculptures out of things washed up by the sea – and then put back in there, tethered underwater, for a year or so. There are plastic mannequins sporting mermaids purse wigs, each object altered, added to. Sheenagh Patience,. above, paints the landscapes of Berneray, walking the local beach, picking up and painting pieces of fragmented pottery and shells.

Marnie Kelty also mines the beach for materials, although these she grinds down in to pigments and inks for her wall paintings. She works, too, in photography, interested in the void spaces, the migration of things and people, the transformation of flotsam by a new environment. Fiona Pearson works in oil and watercolour, painting in semi-abstract fashion, the white sand beaches near her home on North Uist, or working up drawings of cup-marked rocks, interested in the interaction between rock and water. And then Catherine Yeatman, whose abstract landscapes and finely drafted birds aim to capture the essence of place and time.

Edge hebrides, Dundas Street Gallery, 6 Dundas Street, Edinburgh, www.dundas-street-gallery.co.uk Until 9 Oct, Daily 11am–5pm

Don't Miss

The diminutive new Burnside Gallery in Selkirk first opened in the gap between lockdowns last year, albeit for a brief period, but is now up and running again, most recently with this exhibition from illustrators James Hutcheson and David Faithfull. Both have produced new work in ink, here, from artists books to screenprints and drawings, part of a series of exhibitions which has its roots in the strong artistic scene in the Borders.

Ink: James Hutcheson and David Faithfull, Burnside Gallery, 48 Market Place, Selkirk, 01750 491 348,www.burnsidegallery.co.uk Until 30 Oct, Tues - Sat, 10am - 4.30pm (closed 1pm - 2pm); early closing at 1pm on Weds

Subscribe to The Herald and don't miss a single word from your favourite writers by clicking here

https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/19496323.subscribe-herald-just-2/

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here