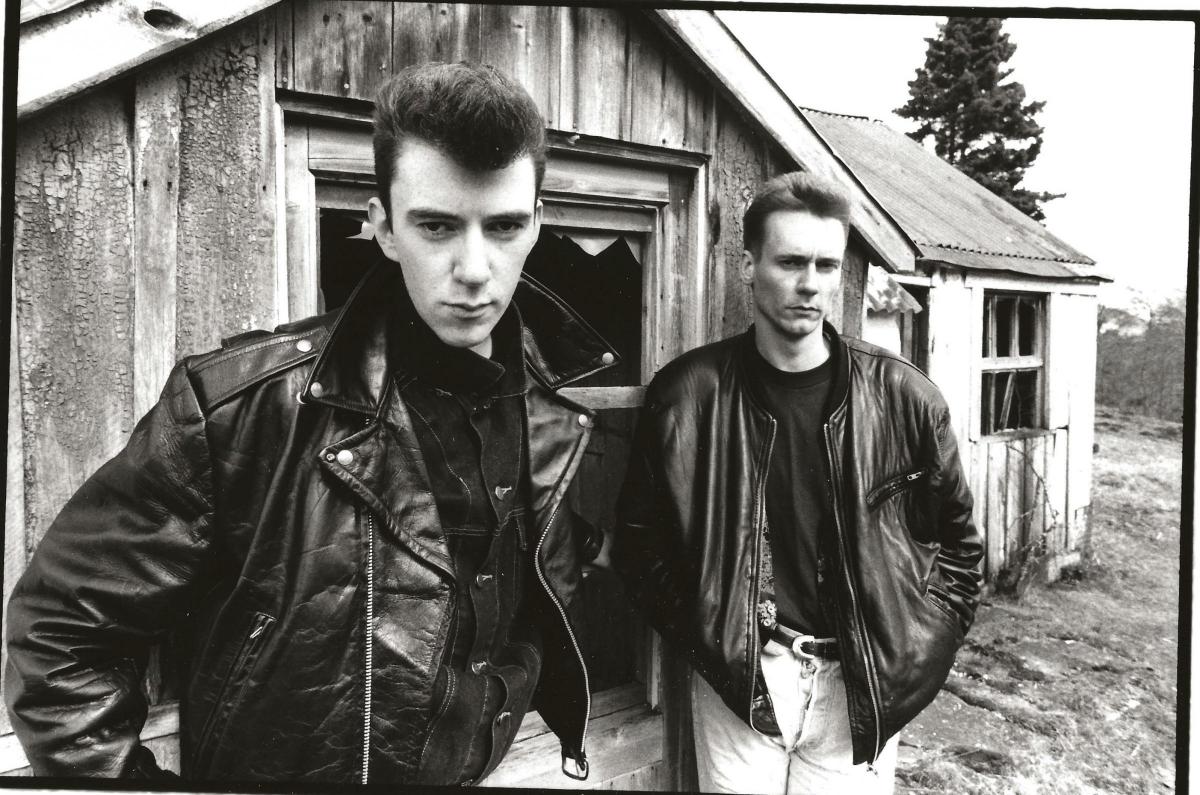

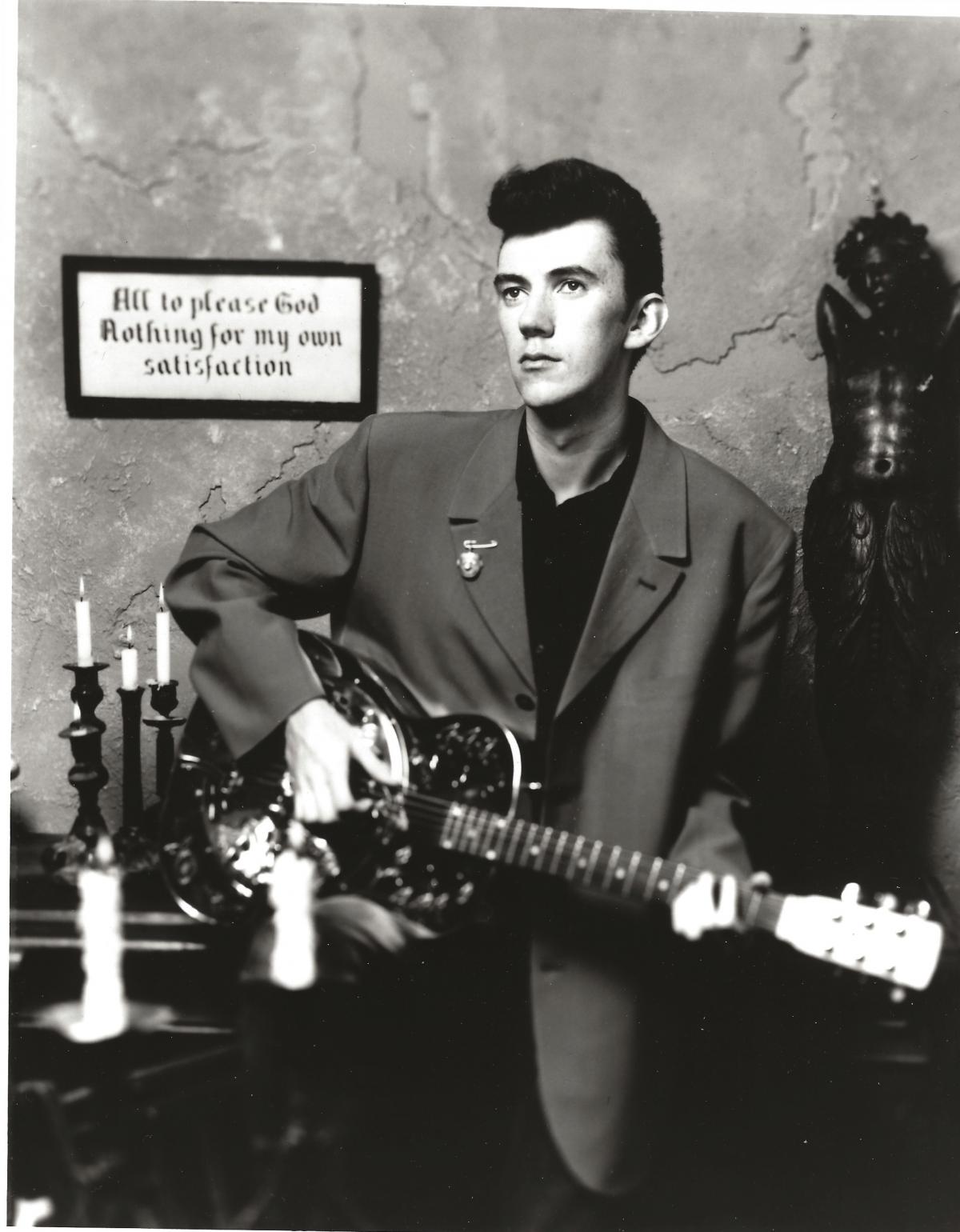

Scotland's Greatest Albums: Love And Money. Strange Kind Of Love – 1988

THERE is an archive piece of film footage that captures a moment in music history. Cilla Black is performing Alfie with an orchestra at Abbey Road Studio in 1966 under the watchful eye of the song’s composer Burt Bacharach. As he asks her to record the vocal track over and over again the singer fears she is failing to please the maestro and suffers a real crisis of confidence.

But it’s quite the reverse. Bacharach is simply pushing for pop perfection. After taping the 28th version, he says to producer George Martin: “How are we doing?”

Martin replies: “I think we got it on Take 4, Mr Bacharach.”

I wonder if James Grant of Love And Money has seen that famous clip. For he would surely identify with what Cilla was being put through. He endured a similar ordeal when his band recorded their second album, Strange Kind Of Love, with Gary Katz in New York.

Katz produced seven of Steely Dan’s classic albums from Can’t Buy A Thrill in 1972 to Gaucho in 1980. Like Bacharach, he also had a reputation for drawing out the very best in musicians.

“We recorded at Chelsea Sound Studio on 42nd Street. We’d walk through Times Square every day to go to work,” recalled James. “And when I say work that’s exactly what we were doing. Gary was a guy who meant business. His attention to detail was off the scale.”

Grant found out just how hard a taskmaster Katz was when they worked on the single, Hallelujah Man. “The album recording went pretty much to plan. But I’ve never known such scrutiny,” he revealed. “I’ll give you an example. I must have sung Hallelujah Man 30 times. I’d never been put under that kind of attention before.

“Don’t get me wrong, if it takes 30 times that’s fine. At the time, I didn’t have real confidence in my voice. The pressure suddenly dawned on me. That was when it kicked in. So I wasn’t enjoying it and it f***** my head a bit. Gary loved me playing guitar. But singing is different. When you criticise someone’s voice it’s very personal. One day we had a pretty full-on argument and I said: ‘I don’t get it. I’ve sung five takes. It sounded good to me’.

“Gary replied: ‘It IS good but I think you can do better.'

"You’re sitting across from Steely Dan’s producer. At the end of the day, you go with that. Hard as it might be.”

Grant has normally had total self-belief. In 1985, he broke away from Friends Again taking two band members, keyboard player Paul McGeechan and drummer Stuart Kerr, with him.

He also recruited bassist Bobby Patterson to form Love And Money with an aim to marry rock ‘n’ roll and dance music. It’s a move he’s never regretted. “This was just me now. I was a songwriter, guitarist and frontman in a band. I WAS Love And Money essentially and I don’t mean any disrespect to the other members,” said James.

Their debut single Candybar Express was set for release on indie-label Stampede, run by Graham Wilson of The Sub Club.

Andy Taylor of Duran Duran heard the song and said: ‘I f****** love this. I want to produce it.’”

But Grant was initially reticent about working with the guitarist. “I remember saying to Graham … I’m not going to do it. He told me I was off my head,” he said. “It was two weeks in Air Studios in London followed by another week at The Power Station in New York. It was quite a powerful carrot to dangle for just one single.

“When opportunities like that come up you think: ‘Is this ever going to happen again?’ I took the decision, I should just do this and worry about it later.”

But it proved an unnerving experience. “Andy did a really good job. I still think the single sounds good, but it was a one-off,” James said. “He was like a big kid, really immature, but obviously minted. In terms of money and fame he didn’t know what to do with himself. I never got the impression he liked Duran Duran very much, or they him. I think that’s still very much the case. I don’t want to sound bitchy but he seemed an archetypal pop star.”

But Grant’s next move really upped the ante. The band recorded their debut album, All You Need Is … with Tom Dowd at The Townhouse in London. He was a member of the Atlantic Records’ production dream team with Arif Mardin and Jerry Wexler. Dowd’s credits included hits by Aretha Franklin, The Bee Gees, Eric Clapton, Rod Stewart, Sonny and Cher and Diana Ross.

“How did we get to work with Tom Dowd? I can only think he liked the songs. And he was probably being paid a lot of money,” James said, frankly. “Tom was a big name producer. Again, it was an opportunity we couldn’t pass up. I didn’t feel overwhelmed by him at all. I had total confidence in myself.”

When the album failed to crack the Top 40 and was not a commercial success, Grant remained undaunted. “I never got any heat from the record company. They seemed to think we were going to be absolutely massive,” he said. “I didn’t think about things like that. I was totally focused on the music. I knew what was coming and that the next album was going to be even better.”

Grant’s optimism was well placed. The songs for Strange Kind Of Love were demo-ed in Parklane and CaVa studios in Glasgow. By the time they reached New York, the band was well-armed. “Gary didn’t do many records so he took a wee bit of convincing to work with us,” revealed James. “I flew out to meet him and we really hit it off. But I never went into those situations thinking I was just some wee guy from Castlemilk. I had absolute self-belief. I didn’t think I was being arrogant. I had complete faith in my own abilities.”

Katz’s name helped attract the cream of the US music scene. Jeff Porcaro of Toto was drafted in to play drums at Sunset Sound Studios in Los Angeles, after Stuart Kerr had dropped out. He’d played on Thriller by Michael Jackson, and his discography includes appearances with Pink Floyd, Paul McCartney and Paul Simon.

In New York, Donald Fagan of Steely Dan hung out with the band and played clavinet on Hallelujah Man while Timothy B. Schmitt of The Eagles did backing vocals on Jocelyn Square. But the recording was a painstaking process thanks to Katz’s almost forensic attention to detail. “We were in the studio every day for eight months. It dragged on and on,” recalled James.

“It cost an absolute fortune. The food bill alone was £45,000 … that’s what we ate when we were in New York. But the record company didn’t give a flying f***. It was the Eighties. We were probably a tax loss. It was mental. And pretty intense.”

Grammy award-winning producer Elliot Scheiner was due to mix the album. But when his schedule didn’t allow, the band did it themselves. It was a disaster. “Paul went home to attend a wedding and when he left we were working on a snare sound,” revealed James.

“When he came back five days later we were still on the drums. It was like psychological torture. We didn’t know what we were doing. Dave Bates, our A & R man hated the mixes. I was utterly raging. I was like … f*** you, you don’t know what you’re talking about.”

His solution was for the band to go on holiday and book into CaVa on their return. “When I got home I went into CaVa and listened to the mix of The Shape Of Things To Come for the first time in over a month,” said James. “The tape was on for about one minute and I was horrified. It was so s***. Me, Bobby and Paul were all looking at one another. We couldn’t believe it. It was astonishingly bad.”

Bill Price was drafted in to mix the tracks and rescued the situation. When Strange Kind Of Love was released it made the UK Top 75 and went on to sell more than 250,000 copies. But a hit single proved elusive. The title track – one of four songs lifted from the album – performed best, reaching No 45.

Aside from missing out appearing on Top Of The Pops, Grant has no regrets. “I think the album still sounds really good. We tried to make records which stood the test of time and we achieved that with them all,” he said. “But I don’t think it’s the one which defines James Grant or Love And Money. Dogs In The Traffic in 1991 does that better. It reflects me more as a human being, artist and writer. It also laid me bare lyrically.

“Strange Kind Of Love maybe defines the idea of Love And Money, the advertising poster version of the band. But even it is not standard pop. If you look at songs like Hallelujah Man, the lyrics are a real monkey puzzle. It requires bit of work from the listener. All good records fall into that category. We were one of those bands that if we got under your skin … that was it.”

The Billy Sloan Show is on BBC Radio Scotland every Saturday at 10pm.

WHAT CAME NEXT

JAMES Grant has made a string of impressive albums in the wake of Strange Kind Of Love. To hear him talk about his music is a highly rewarding experience. His passion is stronger than ever.

“We were part of that lineage that probably started when The Average White Band went to New York to make their second album with producer Arif Mardin in 1973,” he said. “That was massively prestigious. They were just a bunch of guys from Scotland. But they now had this global identity.

“I suppose that was like us. I was no longer this wee guy from Castlemilk. We were playing with the big boys. I liked that.”

What Grant didn’t like however was the additional pressures exerted on him as frontman of the band. “When the whole showbiz thing started I was never really comfortable with all that,” he recalled. “I knew the promotion side of things was coming, but I had this real crisis of confidence.”

Grant has good memories of filming a video for Candybar Express in the Mojave Desert and another for Hallelujah Man in Tokyo. The rest he could live without.

“The reason I was put on this earth was to write songs, make records and be on stage,” he said. “I totally get that there are other things which enable that. But while doing interviews or going around radio stations was essential, I saw it as a chore. I know why it had to be done but I was a bit snarky about it. I wish the whole fame thing hadn’t happened at all. It made me extremely uncomfortable at times when I wanted to be more anonymous.”

Several years ago, Grant played at the City Hall in Glasgow and asked the audience to choose the songs he would perform. “They pretty much picked wall-to-wall Love And Money,” said James.

“I remember thinking, b*******. But they really enjoyed it and so did I. A mate said: ‘Would it be so bad to do some of your older stuff?’ So it was almost like I’d made peace with myself.”

But he has no plans for a Love And Money reunion. “I’d never say never, but it’s not high on my list of priorities,” he said. “I appreciate the value of nostalgia but you can overdo it. It can’t be all about looking back.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here