Beyond Measure: The Hidden History of Measurement

James Vincent

Faber, £18.99

Review by Susan Flockhart

BEFORE clocks were invented, cooks were advised to boil their eggs “for the length of time wherein you can say a Miserere”. The aim, presumably, was to achieve both a spotless soul and a perfect dish but in James Vincent’s experience, you can repeat all 19 verses of the 51st Psalm, and still end up with a disappointingly runny yolk. Perhaps he should have sung it instead, or switched on the wireless and simmered along to a choral rendition of Gregorio Allegri’s marvellous Miserere Mei, Deus, putting the Covid era’s prosaic equivalent – the Happy Birthday handwash – to well-deserved shame.

Whatever its success rate, the Miserere method is an illuminating example of the inventive means by which our ancestors strove to mark, quantify and monitor their world before sophisticated measuring tools were invented. As Vincent points out in his fascinating new history of metrology, every human culture has a unit of length based on the foot; thumbs, shins and arm-spans proved similarly adaptable; and in the 14th century King Edward standardised the inch as equating to three grains of barley, laid end to end.

Interestingly, the “barleycorn” persists as a shoemaker’s measure, with a third-of-an-inch separating UK and US shoe sizes. Meanwhile, contemporary speech contains numerous echoes of defunct units of measurement: in English, a “stone’s throw” once signified how far a man could toss a rock and in Finnish, a “poronkusema” describes a distance of around six miles – which is roughly how far a reindeer can travel before stopping to urinate (the word translates as “reindeer’s piss”).

Naturally, the elastic nature of some of these definitions – not to mention the variability of human bodies and reindeer bladders – led to disputes and according to Vincent, rulers reigned or fell depending on their ability to regulate and enforce reliable units by which the fruits of people’s labour could be measured and traded. Not for nothing is justice symbolised by a set of scales.

In Ancien Regime France, units varied chaotically across the country so that a Parisian “pinte” contained three times as much as a “pinte” in Precy-sous-Thil, and complaints about weights and measures were among the most frequently cited grievances in the “cahiers de doleances” which fuelled the Revolution. “Un roi, une loi, un pois et une mesure” was the rallying cry (“one king, one law, one weight and one measure”).

The metric system was devised as a radical solution. Instead of a random set of units epitomised by the king’s foot, it would be based on the supposedly invariable dimensions of the Earth itself, with its central unit – the metre – derived from a fraction of the planet’s meridian. Although this revolutionary zeal soon dwindled and many French reverted to a muddled mix of old and new units, the system’s arithmetical simplicity meant it would eventually be adopted across much of the world.

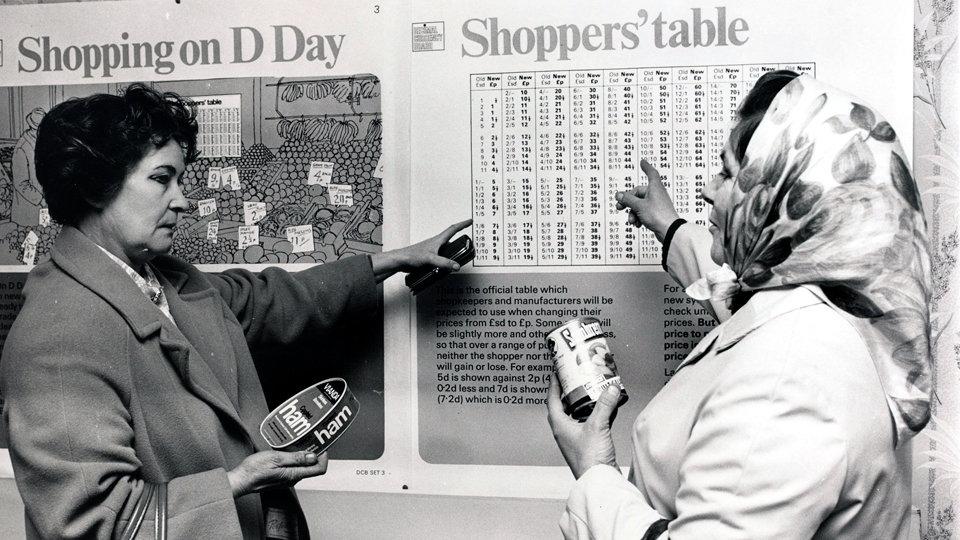

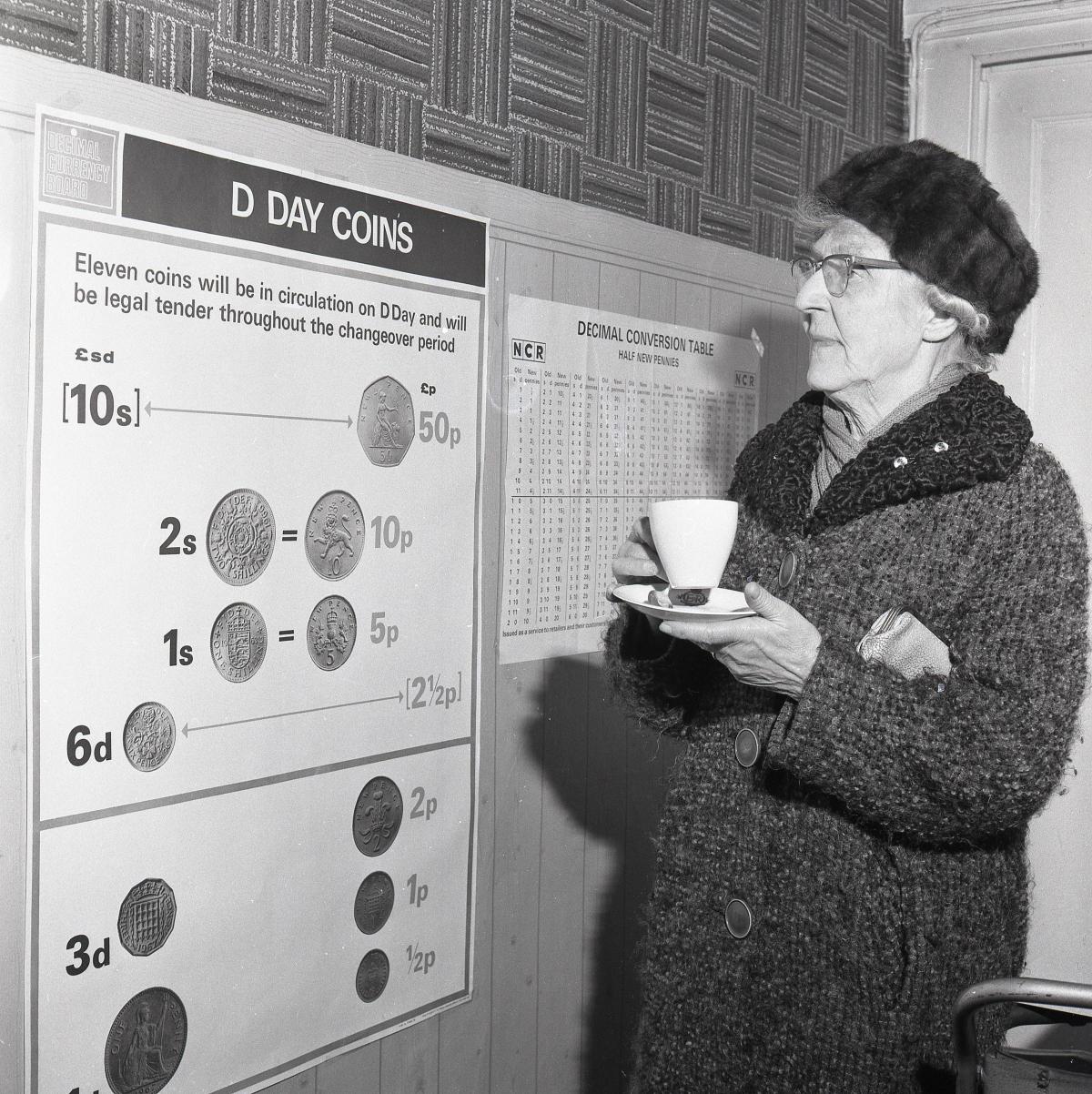

Here in the UK, it took a concerted propaganda campaign to finally push decimalisation over the line before D-Day dawned on February 15, 1971. There was even a government-funded record, with Max Bygraves delivering the woeful vocals: “The half-crown too has gone for good/ A coin that foreigners never understood …”

The F-word was well-chosen. Distrust of Johnny Foreigner and his supposed desire to usurp “the Anglo’s honest pound” had, after all, been at the heart of the very first anti-metric pressure group, the 19th-century, US-founded International Institute for Preserving and Perfecting Weights and Measures. They even had their own theme song, A Pint’s A Pound the World Around, which may well be ripe for a comeback now Boris Johnson is seeking to revive “imperial measures”, in the process, wading into a culture war that’s been raging for centuries.

In one of the book’s liveliest sections, Vincent accompanies ARM member, Tony Bennett, on a clandestine mission to sabotage signposts in his Essex village by replacing metricated distances with equivalents in yards or miles. ARM stands for Active Resistance to Metrification and the organisation’s goal is to preserve the UK’s imperial units.

What drives such passions? Who knows, though historically, many anti-metric campaigners thought the inch, pint and so on had been divinely bestowed and Bennett is not only a Christian but a card-carrying member of UKIP, who’ve been known to wave banners reading: “Rule Britannia – in inches, not metres.” One poll found that half of all Leave voters favour the revival of pounds and ounces. (The same proportion, adds Vincent, want the return of the death penalty.)

Beyond Measure is a hugely ambitious work encompassing a vast sweep of scientific progress and human endeavour, from the evolution of numbers to the construction of the pyramids, the Industrial Revolution and, more recently, the precise redefinition of the metre as equating to 1,650,763.73 times the wavelength of light; and the kilogram as … well, something to do with electrical forces and the formula, m = hf/c2.

I confess that at times, the subject’s complexity defeated me but thankfully, such moments were tempered by lucid prose and plenty of entertaining facts. Did you know that Anders Celsius’s original temperature scale placed boiling point at the bottom as 0°C and freezing point of 100°C at the top? Or that an early thermometer invented by Isaac Newton included temperature benchmarks such as “the greatest heat of a bath which a man can bear”?

Antiquated as all this may sound, Vincent pays tribute to the pioneers whose research created the “scaffold” on which today’s sophisticated scientific knowledge was built, pointing out that even their mistakes helped enlighten their successors. Of course, some mis-steps are unforgiveable and Vincent cites misguided attempts to quantify human “intelligence” – which led to atrocities in the name of eugenics – among the dark consequences of excessive measurement.

Beyond Measure is James Vincent’s first book and as a working journalist, he occasionally deploys on-the-ground reportage to enliven a topic whose abstract nature might otherwise have made for a difficult read. His adventure with ARM’s Tony Bennett (“codename: Hundredweight”) is an amusing case in point, and his travels along the banks of the Nile in search of an ancient Egyptian floodwater monitor are beautifully described.

A little more of this could only have enhanced the work but by any measure, this is an impressive, enjoyable and immensely thought-provoking book.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here