THEIR brutal crimes might have been committed decades ago with killers Graham McGill and William MacDowell evading justice.

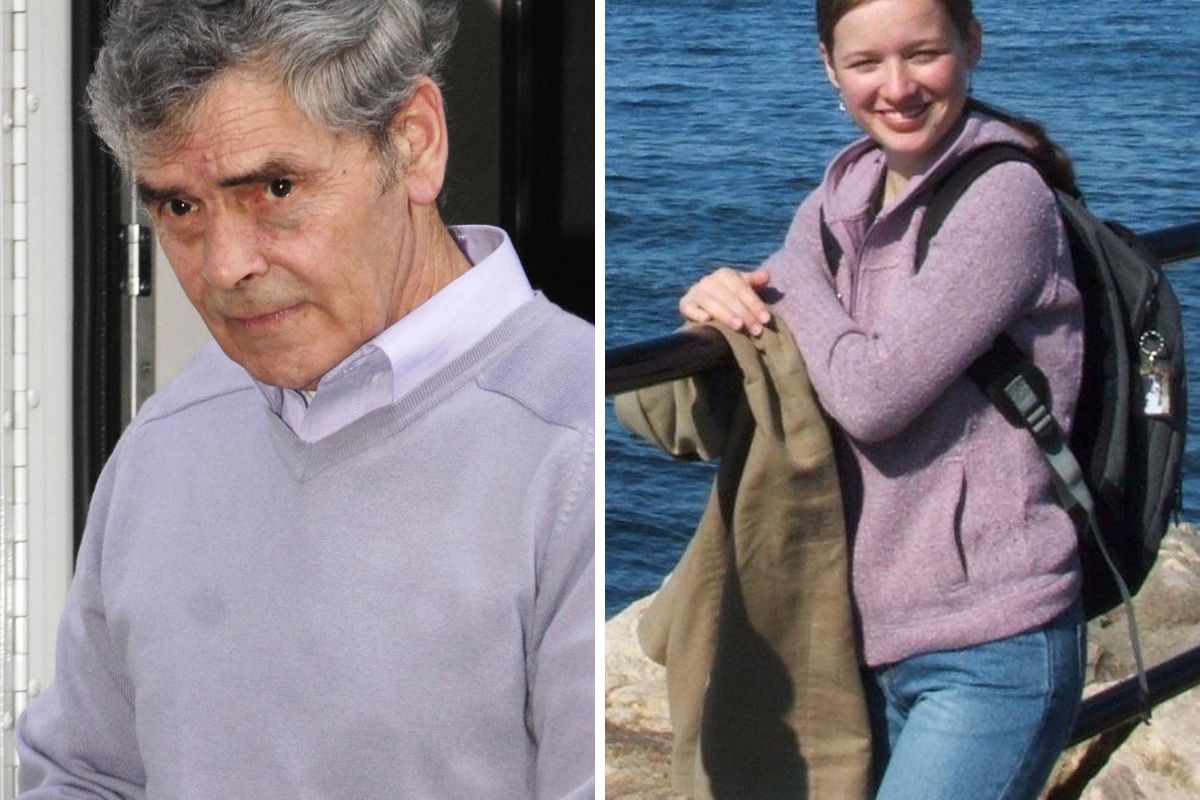

McGill was last year jailed for life for the murder of a mother of 11 in her Glasgow home more than 37 years ago. The 60-year-old was told he must serve a minimum of 14 years in prison after he was sentenced at the High Court in Aberdeen for the murder of Mary McLaughlin.

McGill followed 58-year-old Mary home to her flat in Crathie Court, Partick, in September 1984 where he viciously killed her by strangling her with the cord from her dressing gown.

Read more: Peter Tobin dead: Serial killer's death 'could lead to answers'

However, in 2019, he was charged with murder after a new investigation into the killing matched his DNA to that found on items belonging to Ms McLaughlin.

And last month, William MacDowell was jailed for the murders of his lover Renee MacRae and their toddler son Andrew near Inverness in 1976.

Blood found in the boot of her burned-out BMW was assumed to be Mrs MacRae’s as only one in a billion people would match her DNA profile, samples of which were obtained from an old hairbrush.

Advances in DNA have helped to re-examine evidence from crimes decade ago

Forensic scientist Christopher Gannicliffe told the jury that, since 1976, analysis had advanced significantly and, with the help of new techniques, more evidence of blood on the boot carpet had been detected.

And it is developments in forensic science and DNA profiling in the past 40 years that offer families, who have faced years of torture, the hope of some form of closure.

Historic crimes

GARTCOSH-BASED Scottish Police Authority forensic scientist Carol Rogers says there is no doubt these advances have helped cold cases reach court and lead to convictions years after the crimes were committed.

“When I started out we did blood sampling – you would probably need a bloodstain about the size of a five or 10p piece to get blood grouping. With DNA as we develop it, it becomes more and more sensitive so you need less and less material to be able to get a sample and to get a profile,” she said.

Read more: Glasgow Crime Con: Victims will be put first in bid to crack unsolved cases

“Now the systems that we use are so sensitive that we can get DNA from picograms of samples which is a billionth of a gram. It is tiny amounts that you can’t see. At SPA, we now offer what we call YSTR profiling. It is a technique that only targets male DNA. That becomes really important in sexual offences. The combination of YSTR and our DNA profiling system means we are able to get DNA profiling that even 10 or 15 years ago we would not have been able to get. We are constantly evolving and that is why we are going back and looking at cases and we are getting results which is incredible.

“The McGill conviction, which my colleague Joanne Cochrane gave evidence on, is a case where there was a conviction on the back of forensic science.”

Forensic scientist Carol Rogers helping to unlock secrets of the past

Long before the CSI drama serials, there was a 12-year-old girl growing up in Fife who was fascinated by a true crime programme which sparked her interest.

“There was a murder featured on TV and the couple lived in the middle of nowhere. He had murdered her, but phoned the police and said someone had broken into his house attacked him and murdered his wife,” Ms Rogers said. “This is before DNA when we used blood pattern analysis. Two forensic scientists went in and looked at the blood patterns, looked at his injuries, and recreated the scene.

“This led them to say his version of events didn’t make sense or tie up with the blood patterns. He ended up being charged for murdering his wife because of the blood patterns which revealed he had done it.

“I remember watching that and thinking that is what I am going to do when I grow up. By sheer twist of fate, I had been in the job about two or three years and I was doing my blood pattern training and the two experts from the TV show were taking the training. I must admit I was a bit starstruck.”

Blood analysis

THE extent of forensic science many years ago would have seen a biologist carry out blood pattern analysis and identify body fluids as there was no such thing as DNA profiling.

Peter Tobin was convicted of the murder of Angelika Kluk - DNA evidence was crucial

Ms Rogers added: “It was blood grouping we were doing. We might have been doing some kind of work to identify who the blood came from but it would be nowhere near as discriminatory as DNA, but blood pattern analysis is an art form and it is something we still do to this day.

“The big part for a forensic scientist will be going out to a crime scene and looking at blood patterns to try to establish what might have happened, and reconstruct the offence given the information about where someone has been assaulted or looking for a pattern that is unusual. There might be blood from a suspect to tie them to the scene. It is still a big part of our job.”

DNA profiling came into play in the mid-1990s and Ms Rogers first remembers hearing about it when she was doing a masters degree in forensic science in 1996. “It was beginning to become more popular and when I started in the police lab in 1998 we were using it then. A much older system that was wheeled out for the big cases, but now it is so routine.

“Some of our systems now are very sensitive and we look at 24 areas of DNA. When it first started out you looked at four areas, then 11.”

Mary McLaughlin was murdered in her own home

There are some cases that have never left Ms Rogers including the murder of Glasgow schoolboy Mark Cummings in Royston in 2004 and the southside murder of Moira Jones, both horrific crimes to be involved with.

“You train a long, long time before you go to crime scenes. When you first go you are excited, it is good to be involved in them. It is fascinating and interesting. When you are younger everything is very exciting and new and when you get older, I think you reflect more on the things you are seeing and what you are dealing with. I think that is when you become more aware of your own mortality. That is when it is probably harder to process and move on from.

“You do your crime scene work, go back to the lab and follow that up and talk about it with your peers. You will see it all the way through to the end in court. As well as bringing the families closure, whatever that word means, we get a certain amount of that as well because we follow. I think that helps as we are not just going to crime scenes in isolation.”

It is her work on the case that was crucial when hunting serial killer Peter Tobin, who died earlier this month. He was snared for the murder of Polish student Angelika Kluk in 2006.

St Patrick's Church in the Anderston area of Glasgow where Angelika Kluk was found

Ms Rogers crawled underneath the floorboards where Ms Kluk’s body had been dumped by Tobin and she took the decision not to move the body of the 23-year-old until vital evidence had been secured.

Tobin discovery

RECALLING what led to that decision, Ms Rogers said: “That was a bit of a battle. The reason that I wanted her sampled where she was goes back to a case right at the beginning of my career.

“My boss at the time went out to a murder at Ferguslie cricket ground. A girl called Laura Donnelly had been raped and murdered. He spoke about how he sampled her at the cricket ground because he wanted to be able to link the sexual intercourse to the death. Therefore, you are tying that person to the murder and that always stuck with me.

“When I looked at the crime scene photos before I went to the actual scene in Anderston, it was apparent that this was going to be sexually motivated. Her trousers were undone, police had intelligence as well that we weren’t aware of that suggested that it was sexually motivated.

“It was really important to me because of that lesson I had learned as a youngster. Don’t move her, get the samples taken so when you go to court you can speak to the amount of movement after intercourse. It became so important because they were trying to paint Angelika as an escort, some kind of woman who went around with older men, and they had to convince the jury that she would have had consensual intercourse. Tobin said they had had consensual intercourse and that she went away and had a shower and went shopping. I was able to stand up in court and say no, that is not what the picture we have from where the semen was throughout her body.

“The senior investigating officer, David Swindle, supported me on not moving Angelika.

“I get that with these circumstances the desire to move a body – it is usually a young woman and it is a heinous, violent crime, but by keeping the body there and taking the correct samples we are doing them justice more than moving them and helping to secure a conviction.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel