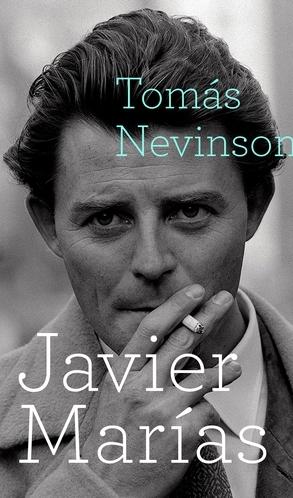

Tomás Nevinson

Javier Marías

Translated by Margaret Jull Costa

Hamish Hamilton, £22

REVIEW BY ROSEMARY GORING

No-one nowadays writes prose like Javier Marías, who died last year a few days shy of his 70th birthday. His sentences, as his long-time translator Margaret Jull Costa remarks in the afterword to this engrossing valedictory novel, seemed to get even longer over the years, unfurling like rivers of thought.

To offer even a few examples here would swallow most of the space available. One sentence near the beginning of Tomás Nevinson runs to more than 100 words; Hemingway Marías is not.

When not writing novels, he liked to translate them from English into his native Spanish. Conrad, Stevenson, Laurence Sterne and Sir Thomas Browne were among the writers he favoured. But the writer he most stylistically resembles – at least to my eyes – is Henry James who, as Marías noted, in his zeal to achieve clarity became “utterly oblique and obscure”.

The same might be said of Marías himself. For readers, this can present something of a challenge. Time – and quiet – is required to read a novel like Tomás Nevinson.

REVIEW: The Herald's pick of the best new Scottish books of 2023

It took me the best part of a fortnight to consume its 600-plus densely-packed pages.

It cannot be read greedily like a blockbuster; rather you need to approach it as if you had nothing else to do, trusting that the hours will be well spent. Like so many of Marías’s previous books, it is nominally a thriller, but not as defined by the bestseller lists. There is no whizzbangery, no car chases, little to no sex and violence. The action, such as it is, takes place mainly in the narrator’s head.

In the acknowledgements, Marías says that “a sliver of an idea” comes from John le Carré. My guess is that the novel he had in mind was A Perfect Spy, in which a double agent relives his past while it hastens to catch up on him. Like le Carré’s Magnus Pym, Marías’s Tomás – Tom – Nevinson has spent his adulthood leading a life of subterfuge and deceit, which necessitated the assumption of numerous aliases. Now in his 60s, he is looking back and assessing if it was all worthwhile.

Nevinson is an intelligent man; well-read, culturally eclectic, introspective, thoughtful, sensitive. He can quote from memory – and more or less accurately – Shakespeare, TS Eliot, Wilfred Owen, WB Yeats and many more.

What concerns him, from first page to last, is whether it is better to act when you have the opportunity or whether you should wait until there is compelling evidence that a suspect is indeed guilty of the crimes of which he or she is accused, Hitler being a prime example. What if in 1932, Friedrich Reck-Malleczewen had taken the opportunity to assassinate the Führer? Might the Holocaust have been averted and history changed?

Nevinson’s mission here, however, is not to stop a calamity happening but to revenge one that has. In doing so he revisits events of 20 years before when, having been retired for some time from the British secret service, he is persuaded back into the field by his mentor Bertram Tupra.

Reluctant at first to leave a desk job at the embassy in his native Madrid, Nevinson agrees to up sticks, leaving behind his wife and child – last seen in Berta Isla (2017) – and settle in a town he calls Ruám in north-west Spain. Three women, Tupra tells him, have been identified as possible participants in a heinous crime carried out in 1987 by ETA, the Basque terrorist group.

They may also have links to the IRA and though they had been dormant for some years they could yet be revived to take part in another atrocity. With the clock ticking it is Nevinson’s job to discover which of the women is guilty – whereupon he may be asked to kill her.

To say that progress is slow is an understatement. Hundreds of pages go by as Nevinson – now known as Miguel Centurión – tries to uncover the evidence that will decide one of the women’s fate.

Inés Marzán is a restaurateur, long-limbed, big-boned and “very far from being a beauty”. Soon Nevinson and she are sleeping together. Celia Bayo – “a jovial soul in her early 40s and very slightly on the plump side” – is a teacher at the school where Nevinson has a job. Thanks to a hidden camera in her home he views her having rambunctious sex with her “rather shady” politician husband. No-one in Ruán has a bad word to say about her.

REVIEW: Georgina Moore's debut novel is set in the Isle of Wight

Then there is Maria Viano whose children Nevinson is engaged to teach English. She lives with her husband, an arrogant big fish in a goldfish bowl, in a mansion in a posh part of town. She is attractive, “subtly” so, well-respected, and seemingly beyond reach of our narrator.

Which of the three women might be capable of acts of terrorism?

Among the few clues Nevinson has to go on is that in another existence the elusive woman was of Irish stock. But how to discover which one it is? Do freckles – a sure sign of Celtic blood – count for anything? Or that someone responds to a Northern Irish accent?

He has little more to go on than coincidence or gut instinct or the fact that one woman appears to be more guarded than her fellow suspects. Pressured into making a decision by Tupra, Nevinson must decide to make his move or back off.

“We’re not ETA or the IRA nor are we Protestant paramilitaries or the mafia,” Tupra insists, unconvincingly. But what is Nevinson to do? Had he been in Reck-Malleczewen’s shoes, would he have killed Hitler?

Tomás Nevinson is a literary novel, and all the better for that. In it, Mariás demonstrates why so many of his peers believe him to be among the greatest of contemporary novelists. Like a secret agent, he is an observer and an eavesdropper, and an inventor.

If you’re already a fan, you’ll know what to expect and rejoice. If you’re not, what a treat you have in store.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel