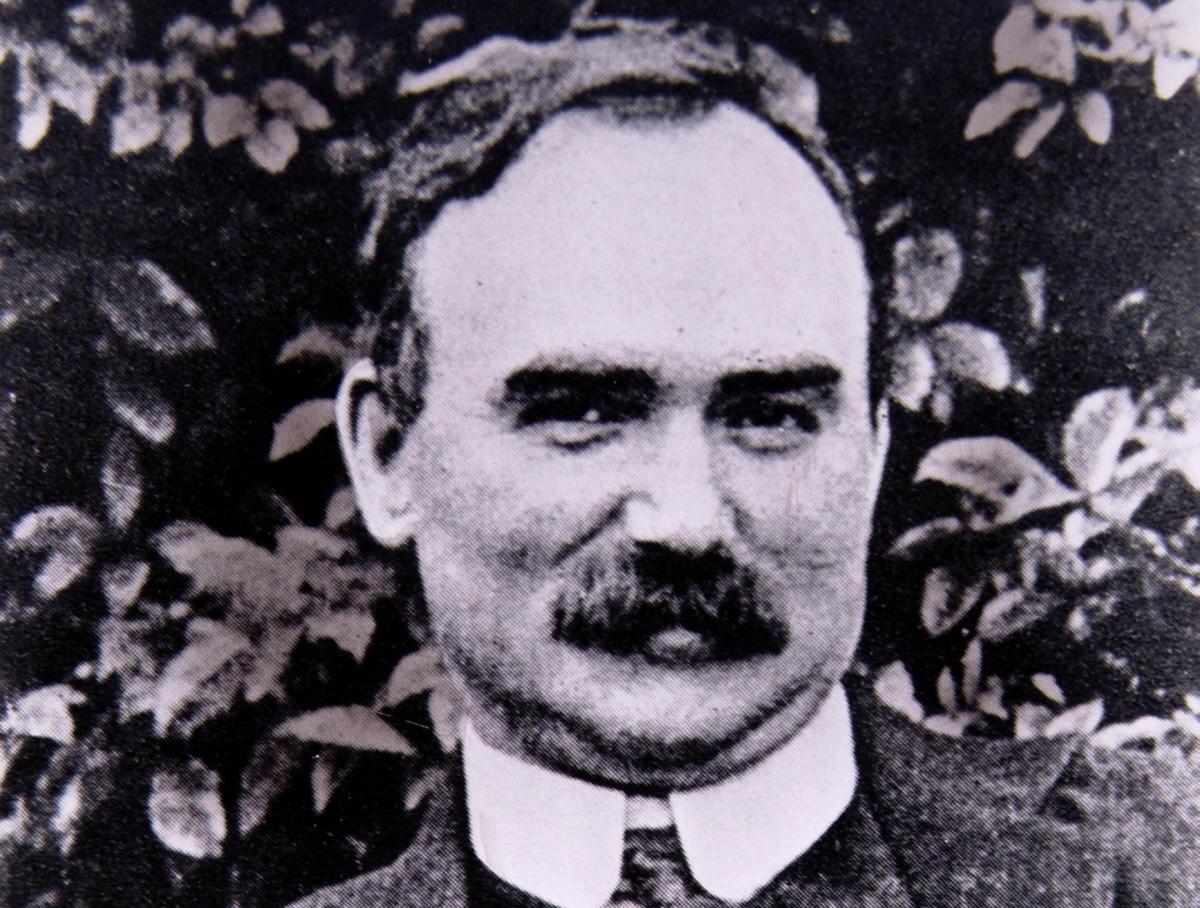

A century ago on Easter Sunday, a rebellion aimed at ending British rule and establishing an independent Irish Republic was brutally quashed by the British Army. Thousands of rebels and civilians were killed or wounded, and co-organiser, Irish Citizen Army leader James Connolly, was executed by firing squad. How should we remember him? His great-great nephew Sean Bell, who learned about his ancestor from his father, Ian Bell, reflects on his legacy

AS usual, James Connolly was right. In the aftermath of the Easter Rising, as rebels became prisoners of that which they had sought to overthrow, the commander of the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) predicted that the revolution's rank and file would not remain shackled for long. Only the signatories of the Proclamation – the dream they had dared to call a "provisional government" – would be shot, he said.

In their desperation, the families of the condemned might have briefly convinced themselves otherwise. In Ireland and beyond, the ongoing execution of the insurrection's motley, quixotic, defiant leadership was proving unpopular. Even those sympathetic to the British state generally preferred that its barbarism not be articulated by firing squad. Any sane observer would have seen it coming. Instead, the British Army was in charge, and sanity was in short supply.

Connolly, born into the slums of Edinburgh, understood that he would die in Dublin before almost anyone else. By the time he went before his military tribunal – a court-martial, no less; the army never forgives a desertion – Major General Sir John Maxwell, Dublin's hastily appointed "military governor", was receiving increasingly frantic entreaties from Asquith's government to cease the executions, lest public opinion turn against them further. Maxwell shrugged it off as cold feet. There were agendas more powerful than the popular will at play, and he had loose ends to tie up.

At midnight on May 11, 1916, Connolly's wife and daughter, Lillie and Nora, were brought to his side at Dublin Castle. He was dying already; wounds sustained in battle would have killed him soon enough. Nevertheless, his captors had seen fit to rouse him from his first real sleep since the Rising's end to tell him he would be shot at dawn.

"Don't cry, Lillie," he said, as she sobbed at his bedside. "You'll unman me."

"But your life, James. Your beautiful life."

"Hasn't it been a full life, Lillie?" he asked. "And isn't this a good end?"

On May 12, 1916, Connolly was transported via ambulance from the castle's Red Cross hospital to Kilmainham Jail, leaving his nurses in tears. Unable to stand, the "Commandant General" faced the firing squad propped in a chair. As murders go, it was sufficient enough for legend. I honestly don't know if it was a good end. I do know that it was a brave one.

Seventy years later to the day, my father held his newborn son for the first time. For a man who knew his history as intimately as Ian Bell did, the date of my birth was the kind of spooky coincidence that could challenge one's disbelief in omens. For much of our family in those intervening decades, Connolly's legacy was largely unspoken. For me, from the day I was born, it has been unavoidable. I wouldn't have it any other way.

In his own youth, my father discovered the story of James Connolly and made it a part of his own. The initial connection, however distant, was clear enough: his grandmother’s father – my great-great-grandfather – was John Connolly, first mentor to his younger brother James in a Jurassic socialism still discovering itself amidst Victorian smoke and sprawl. Born into the poverty of the Cowgate, Edinburgh’s semi-subterranean "Little Ireland", the still-evolving ideology seemed as good a means as any for enduring an era that killed people like them as a matter of course.

The facts were these, but my father wanted to know more. In his determination to do so, he relied upon the sometimes uncertain collective memory of working-class Edinburgh, ageing relatives whose recollections were either reluctant or rose-tinted, unwavering partisans who boasted of close connections to the still-unfolding Troubles, and eventually, like his father and Connolly before him, the library, which proved to be his most valuable resource.

Years later, my own process of discovery would be far more straightforward: I had my father, and there was never a better teacher, especially in those matters that can't strictly be taught.

My father showed me how the past can inform the future, and he did so with nothing more than words and the feeling that lay behind them. He was not Connolly's archivist or acolyte; he was, in thought and deed, his successor, though he would never have admitted to such a distinction. I defy all comers: try and tell me I’m wrong.

It was he who told me of the ancestor who gave me a middle name, providing the rare books and rarer perspectives necessary to understand more than the mythology. At the same time, he never once told me what I should think of "Uncle Jim". My father understood that Connolly was too large to be a mere family legend. Revolutionary socialism was not some heirloom to be jealously guarded. Connolly belongs to the world he endeavoured to change.

On the other hand, my father would occasionally joke: "If anyone ever gives you trouble, remember: we outrank them." At least, I think he was joking.

Perhaps it suffices to say there was an understanding between father and son of what Connolly meant to us, one that I still find hard to articulate. It was, in a word, personal.

In the early 1990s, as the Provisional IRA's campaign of armed republicanism reached its twilight, old sensitivities stirred in Scotland once again. The James Connolly March, at the time a small but dedicated annual event in Edinburgh, faced threats of counter-demonstrations from loyalists and sympathetic neo-Nazis, bussed in from across the border. The kind of confrontation that usually transpires when fascists come to Scotland was anticipated by all. In response, a panicked Edinburgh City Council banned the march.

Once it became clear that this would achieve nothing beyond inflaming the situation, my father was sent, in a journalistic capacity, to report on what followed. In consequence of his writing, his name was circulated among the British far right, along with his home address, the residence of his wife and child. Fascists being famous cowards, little came of it, and the bitter lesson it taught my father was nothing he did not already know: Connolly's legacy is far from academic. Like I said, it was personal.

Today, my interest is both personal and political. I am a Connolly and a Connollyite. From my ancestor's example, I progressed to Marx and Engels, Che Guevara and Angela Davis, Subcommandante Marcos and Hugo Chavez. Because of the man they killed at Kilmainham, my dream has a shape, and its name is the workers' republic. But it is to the man who taught me of James Connolly that I am most grateful, and who I hold in the highest regard. In doing so, I know I am not alone.

Try to define Connolly today, and characterisations abound and multiply without contradiction. A working-class boy who never viewed the poverty of his origins as anything less than an affront to humanity. An Edinburgh socialist whose omnivorous self-education was carried out through application of the old Scottish idea of the democratic intellect. An Irish republican who never once allowed romanticism to obscure the social and material causes of his radicalism. A syndicalist union organiser who saw, in the struggle of his fellow workers and agitators, a means to change the world. A scholar who despised militarism, and led a citizen army as a result.

The questions facing those who pay heed to Connolly's teachings today are both obvious and overwhelming: where next? How do we take the most eloquent and coherent articulation of national liberation yet produced – endlessly invoked, forgotten, misremembered, borrowed, built upon but forever unrealised – and put it into practice? Some, like Tom Nairn, Scotland’s most important postwar political thinker, pursued the theorical aspect, chasing Marxism and nationalism into the 20th century and beyond, still searching for the workable synthesis that came so naturally to Connolly. Others picked up the gun.

Surveying the ways in which Connolly has been remembered is a good education, if you know what to look for, in those aspects of his life and thought that have been carefully forgotten. To my knowledge, there are two monuments to Connolly in the United States: a fine-looking statue in Chicago and a dignified bust in Troy, New York, both areas where Connolly either lived or organised during his time with the Industrial Workers of the World. With weary predictability, the word "socialist" doesn't appear on either of them, but that’s America for you. Another statue stands in Dublin, which at least has the decency to be accompanied by his own words: "The cause of Labour is the cause of Ireland; the cause of Ireland is the cause of Labour."

In Edinburgh, the city of his birth, there exists only a plaque in the Cowgate, sometimes accompanied by a periodically vandalised portrait. When, in the company of BBC Radio Scotland, I recently showed it to the academic Kirsty Lusk, her reaction was simple: "I thought it would be bigger."

Cynics know better. In Scotland, Connolly's legacy is tolerated, so long as it can be safely ignored. Admiration is sometimes expressed, even by Blairite spin-doctors, so long as no-one holds them to it. With the advent of the Easter Rising's centenary, that cowardly position has become untenable. As North Lanarkshire Council recently discovered to its cost, even the most benign expressions of historical memory – "flegs", as they say – can provoke those with a boundless and not entirely mysterious enthusiasm for intimidation.

Meanwhile, not for the first time, ham-fisted attempts have been made to use Irish history as a cudgel with which to beat modern Scotland, and feed the dark suspicion that beneath every supporter of independence lurks a violent Fenian by any other name. In response, the Milquetoast moderates of Scottish nationalism stumble into retreat, fretting about the possible consequences of acknowledging history they have no right to deny, while the SNP – whose enthusiasm for the self-determination of nations other than their own has always been curiously variable – maintains a careful, diplomatic silence. That impeccably bourgeois party has, and always will have, bigger fish to fry.

In Ireland itself, commemoration of 1916 has become a kind of year-long carnival, the spectacle of which should shame Scotland for its reticence. Yet much of the worthy, necessary discussion now underway in the Republic is a corrective to decades of couthy bromides and selective amnesia. Put aside romance and hagiography: the central lesson Connolly taught much of mainstream Irish republicanism, particularly those sections composed of conservative Catholics intoxicated by their own self-mythologising, was that someone like him must never again be allowed to flourish or achieve influence. The working-class were footsoldiers for the cause, and should any of them have ideas above their station, they must not be permitted to hold their superiors' feet to the fire with threats of independent revolutionary action. As the historian Owen Dudley Edwards put it: "The failure to take up Connolly's banner is in itself a tacit declaration that he is better dead – gloriously dead, of course, but dead none the less."

In planning their rebellion, the decidedly non-socialist Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) – a Fenian secret society in the classic 19th-century mould, unsophisticated in their republicanism and conspiratorial by nature – worried that Connolly’s freshly formed Marxist militia might beat them to the punch. Spiriting him away to a deserted Dublin brickworks, their "Supreme Council" confronted Connolly’s with aggressive negotiation, which yielded, to the surprise of everyone, a counter-intuitive though strategically logical collaboration: the ICA came together with the IRB, and thus the Rising was born. In later decades, potential troublemakers would instead be greeted by denunciation or bullets. Unsurprisingly, this would be met by response in kind.

From my particular perspective, I have seen Connolly’s legacy too often ignored. In his lifetime, my father saw it abused. From the 1970s on, as Northern Ireland darkened into an age of hard choices and precious little heroism, plenty of ruthless and bloodthirsty men sought to summon Connolly’s spirit through unconscionable deeds. I have no trouble making my peace with that. The dead cannot control what murderers will do in their name. Just as any line drawn between a 19th-century German doctor of philosophy and Stalin's gulags inevitably evaporates, no-one has yet drawn a compelling syllogism that begins with Connolly and ends with knee-capping and car-bombs. It won't stop them trying.

Experiencing Scotland over the past few years has been an enlightening exercise in what happens when countless dreams exist simultaneously, and through alchemy or absurdity, coalesce towards a shared purpose. If contemporary Scotland enjoys any parallels with the Easter Rising, its motivations and after-effects crowded and confusing, that might be chief among them. My own dreams were passed down from my family, and I make no demands that they be shared by anyone. However, to those who style themselves as the pro-independence left, I would suggest that to exclude or forget the political philosophy of Connolly would be to sacrifice more than they can afford to lose. What remains unthinkable for the British state and the Scottish establishment was self-evident and necessary to Connolly more than 100 years ago. His lessons remain, for all brave enough study them.

A postscript from history: as scenes go, it would shame Kafka. In June 1916, Lillie Connolly called on Major General Maxwell to collect James's meagre personal effects. A month before, he had ordered her husband's death. But that, apparently, was no excuse to be uncivil. Faced with the woman he had made a widow, he held out his hand.

Lillie's eyes met his. Her gaze remained steady. I will never understand how.

Her hands remained behind her back. That, I understand.

Some things do not deserve civility, or respect, or obedience. This was the last lesson James Connolly had to teach us. Beyond the different world he dreamed of in prose and approached in action, it may be what frightens his enemies most, even to this day – the idea that those bound by the farcical rules of class and reverence, oppression and fear, might one day simply cease to play the game. The politeness of those expected to tolerate the intolerable will always, eventually and inevitably, run out.

As the world has turned, some see a Britain that reformed itself from the blood-soaked empire of 1916 into a liberal democracy – a 21st-century multinational state whose inconsistencies and illogicality have faded like old wallpaper. I don't share that perception, nor do I envy it. When I look at Britain, and all of the injustices it carries with it, I see what Connolly taught me to see. I see what killed him.

Despite the best efforts of small minds, Connolly's vision is still with us. It is now the responsibility of a new generation to decide what that vision means to us. In doing so, we should not forget the example of those who showed us the way.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel