AS a mental health practitioner, I have noticed a distinct increase in the use of psycho-pathological terms in our common vernacular. Last week, yet another diagnosis was plastered across the front pages when it was reported that Donald Trump was deemed (by his advisors) to be afflicted by ODD (oppositional defiance disorder), a condition usually ascribed to children or young teens and whose primary symptoms include temper tantrums, persistent questioning or flouting of rules, defiance to comply, blaming others for one's own mistakes and excessive arguing with adults. There’s more, but you get the picture, I’m sure.

Terminology that previously nestled discreetly in the domain of psychiatrists and psychologists, has muscled in on everyday dialogue with all the bravado of a new kid on the block. Just like the gold cladding (presumably fake) that bubble-wraps Trump Tower in New York City, our use of these specialist terms is bold and unselfconscious.

Throwaways such as “he’s definitely on the spectrum” or, “she’s so borderline (personality disorder)” pepper workaday conversations. We don’t even need to be in an armchair to make these clinical observations. They can happen down the pub, at the bus stop, on the landing of the close or via Facebook and Twitter. I remember the moment I became aware of the shift from professional to public ownership of diagnostic terminology. It was the day news broke of Trump’s proclamations during his boys-will-be-boys bus ride to a TV studio where he was due to be interviewed about his election campaign. Unaware that he is being recorded, Trump magnanimously enlightens a male journalist on what women really want. Apparently, all you have to do is “grab them by p*****”.

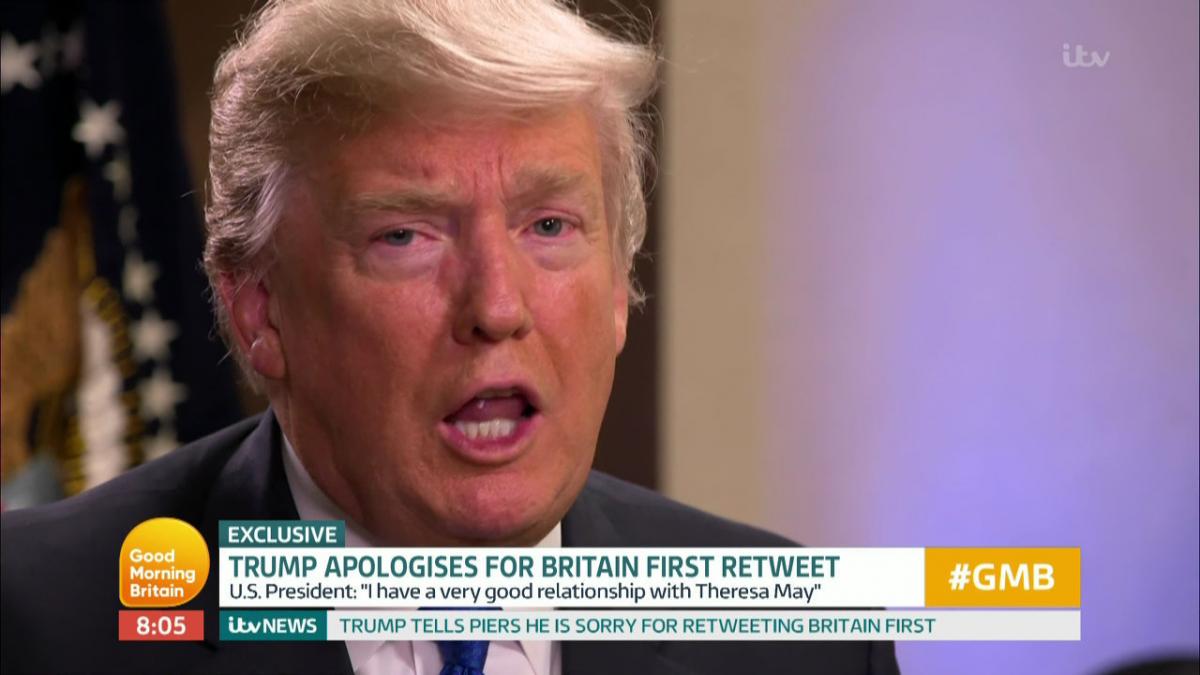

That same day, I was standing in a supermarket queue and two women in front of me were discussing the story when one said: “He’s defo NPD.” The other woman looked slightly puzzled but nodded in agreement. NPD is an abbreviation for narcissistic personality disorder. It’s a label that is stuck on Trump every day of the week (as if he cares). For the extreme narcissist, any attention – even if it’s really, really bad – is better than none. The only thing that matters to someone with NPD is that they are at the centre of life, the universe and everything (thereby assuring themselves that they actually exist).

The popularisation of psycho-terminology is a double-edged sword. It’s heartening that people are becoming more aware of, and sensitive to, mental health and the psycho-patois that surrounds it. Demystifying the language helps to destigmatise mental illness. When I was growing up, anyone with a mental health issue was described (usually in hushed tones) as “suffering with their nerves”. This convenient, catch-all descriptor covered a multitude of mental and emotional states, ranging from the totally psychotic and delusional to just being a bit out of sorts. “Nerves” triggered all kinds of wild imaginings about what was going on in the mind of the poor soul who was “suffering from” them. Paradoxically, the lack of specificity in this blanket description, had a kind of levelling effect, putting everyone with mental health problems in the same boat. This meant that sufferers were, in a strange way, less stigmatised and perhaps better tolerated within their community. I remember going to the annual fete at the local asylum near the village where I grew up. It was a big community event with many of the locals feeling some kind of moral obligation to support it.

Today, though, all the old asylums are gone and, overall, it’s a good thing. People are more willing to acknowledge mental health problems and are more vigilant about caring for their psychological wellbeing. Mental health charities and user forums have done great work in the provision of psycho-education and de-mythologising the black hole that was once mental illness. With this, however, comes the increased risk of over- and misdiagnosis of what were once “normal” states of being. The biggest money-spinners for the pharmaceutical giants are anti-depressant and anti-anxiety drugs. Their use is widespread and growing by the day. There’s a time and a place for psychoactive drugs and they provide necessary support for many. Sometimes, though, the best medicine of all, is to learn to bear the pain that is necessarily a part of the human condition. Grabbing a label and a pill to explain and numb the dilemmas and difficulties of just being human, or putting blind trust in those who are quick to diagnose, is a recipe for madness. The biggest delusion of all is buying in to a world where we believe we’re entitled to feel happy all of the time. Dream on.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here