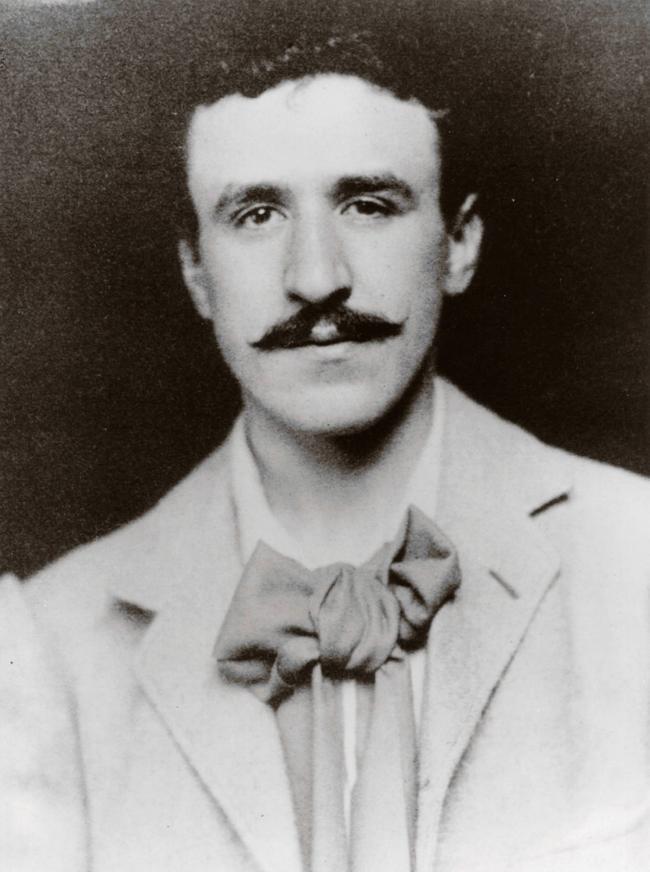

SOMETIMES critics get it wrong. Very wrong. Back in 1895, a journalist writing in this newspaper – then called the Glasgow Herald – had this to say about Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s radical design for Glasgow School of Art: “I cannot perceive that this type of architecture will command any permanent admiration.”

Just over a century later, the Renfrew Street structure was voted Britain’s best building of the last 175 years, highlighting not only how mistaken our critic was, but how renowned Mackintosh and his work has become, winning him legions of admirers around the world, including the likes of Brad Pitt, Barbra Streisand and Princess Margaret.

It took time for the world to catch up with Mackintosh’s pioneering and very modern aesthetic vision, not least in the Victorian city of his birth, but the deep-rooted creative bond he cultivated with Glasgow is now acknowledged globally, celebrated in similar terms as Gaudi’s relationship with Barcelona and Frank Lloyd Wright’s association with Chicago.

Indeed, Glasgow’s cultural transformation and reinvention over the last 30 years coincided with the growing appreciation of Mackintosh’s work as an architect, designer and artist; at the same time as “Toshie”, as he was affectionately known by friends, was giving Glaswegians pride in their built heritage, he was also helping them redefine and re-imagine themselves in more creative terms.

But familiarity can sometimes lead to complacency, and those of us who live in or regularly visit Glasgow are perhaps guilty of taking his contribution to art, design and architecture for granted. How many of us walk past his buildings every day without looking up to take in their beauty? And how many of us covet great architecture and design abroad while forgetting to explore what’s on our doorstep?

READ MORE: Twelve places to visit to discover Mackintosh's life and work

This sense of reminding ourselves why he still matters is at the heart of the Mackintosh 150 celebrations, which brings together an array of exhibitions and events across Glasgow and beyond. The diverse programme encourages us to look again at the legacy and influence of Mackintosh – born in Townhead, Glasgow, in 1868 – to rediscover the buildings, designs and items we already love, and find new favourites amid the fully restored works going on show this year for the first time.

The exhibition at Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow, which runs till August, showcases the astonishing breadth not only of Mackintosh’s talent, but that of the many other artists, designers and associates who worked with him to create the Glasgow Style that would make such an impact across Europe in the early 20th century.

In June, Kate Cranston’s Willow Tea Rooms in Sauchiehall Street, Glasgow, will re-open after a £10m facelift, while in October, Mackintosh’s stunning oak design for her tea room in the city’s Ingram Street will be the centrepiece of the Scottish Design Galleries at the new V&A museum in Dundee.

At the same time, with two of Mackintosh’s architectural masterpieces – Glasgow School of Art and Hill House – either being restored or in need of major work, Mackintosh 150 organisers hope to focus minds on ensuring his legacy is preserved.

According to Stuart Robertson, director of the Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society, based at Glasgow’s Queen's Cross Church, one of Mackintosh’s first major commissions as a young architect and designer, part of the enduring appeal lies in his spirit of modernity.

“There’s something about Mackintosh’s designs that are utterly timeless,” he explains. “They are still look very contemporary today, but 100 years ago they were truly revolutionary. Take, for example, the domestic rooms of his own house, which have been recreated at the Hunterian Art Gallery. You only have to visit the Tenement House museum in Glasgow, a recreation of a typical interior of the time, to see how radical Mackintosh was. They represent two different stratospheres.

“Mackintosh advocated simplicity and decluttering, which was a pioneering approach at the time. Habitat founder Terence Conran, who had a big influence on our current ideas around interior design, was very influenced by Mackintosh. The world was still picking up on Mackintosh’s ideas 70 or 80 years after he’d created them.”

Robertson believes Mackintosh was also a pioneer in terms of the positive social and psychological effects he wanted architecture and design to evoke.

“He was an all-round talent who thought in terms of complete buildings and rooms. We see this very clearly at Scotland Street School in Glasgow, where he was trying to create a stimulating environment for the children to learn in, hoping his design would encourage them to be imaginative.

“Architects and designers still learn from that approach today. I love the fact that Mackintosh is such a wonderful road in for people to experience art and architecture at so many different levels.”

The Society, a charity which depends on donations and volunteers, has been central to the appreciation, protection and restoration of Mackintosh’s work for more than 40 years. And, as the use of its headquarters as a music, arts and wedding venue highlights, it believes in linking the artist to Glasgow's wider arts movement.

“Mackintosh 150 is all about encouraging people to appreciate the amazing cultural opportunities in Glasgow. We view Mackintosh as a gateway to all the wonderful architecture in the city."

Among those who already appreciate the city's world-class reputation is Mackintosh aficionado Brad Pitt. The actor has long been an admirer of his work, having first visited Glasgow in the 1990s, returning in 2011 while making the film World War Z, making a visit to Hill House in Helensburgh with his then wife, actress Angelina Jolie.

Pitt acknowledged Mackintosh’s direct influence on his own designs for upmarket furniture maker Pollaro.

"It started with my introduction to Mackintosh’s Glasgow rose, which is drawn with one continuous line," he said in an interview. "But for me there is something more grand at play, as if you could tell the story of one’s life with a single line.”

Indeed, following the 2014 fire at Glasgow School of Art, which destroyed the iconic library in “the Mack” as the building is known, Pitt has been active in fundraising for the restoration and is a member of the board of trustees for the project, alongside former Doctor Who star and school alumni Peter Capaldi. The building is due to re-open to students and visitors next year after a £32m overhaul which includes the compete rebuilding of the library to Mackintosh's original plan.

But Mackintosh continues to influence the look of today’s urban landscape in many ways. Indeed, prize-winning Scots architect Alan Dunlop, an alumni of the Mackintosh School of Architecture at Glasgow School of Art, says The Mack was a direct inspiration for one of his most celebrated buildings, Hazelwood School in Glasgow, which was designed specifically for children with sensory impairments.

“There have been so many times during my career when I’ve asked myself ‘how would Mackintosh do this?’” he says.

“The classrooms at Hazelwood are placed to the north so that an even level of natural light comes into the building. This is very important for children who are partially sighted as it means they can rely on a decent level of ambient light throughout the day, uninterrupted by direct sunlight.

“The idea for this came entirely from Mackintosh’s work at Glasgow School Art, those big windows that allow artists an even spread of light all day.

“The lack of ornamentation at Hazelwood, the concentration on expressing structure rather than decoration, are all influenced by Mackintosh. He remains influential on all the work I do.”

As for the position Mackintosh occupies in Scottish architecture and design, Dunlop, a visiting professor at Robert Gordon's University in Aberdeen who receives architectural commissions from all over the world, is unequivocal.

“The roll call of great Scottish architects is very impressive,” he says. “We have Robert Adam, David Hamilton, Alexander Thomson, Basil Spence. But Mackintosh stands head and shoulders above all of them.

“His reputation and significance, in Scotland and beyond, is profound. As one of the originators and early practitioners of the modern movement he was working at a time when architecture was heavily ornamented – you only have to look at the difference in approaches between Glasgow School of Art and Kelvingrove Museum, which was built at the same time and very much fitted the style of the day.

“Mackintosh wanted to do a different kind of architecture, pared down and functional, but still with roots in the Scottish building tradition.

“Glasgow School of Art, finished 1909, is still a functioning school of art. It was designed specifically for the people who would use it and it remains an incredible building.

“Mackintosh wasn’t interested in the ‘machines for living in’ that the likes of Le Corbusier designed. His buildings were functional and restrained but they were also beautiful, and that is what makes them so remarkable.

“We see this at Hill House, the influence of the Scots Baronial tradition, so it is specific to its place. He was also a brilliant and complete artist, as we see from his watercolours. His draughtsmanship is astounding. He’s not only a great Scottish architect, in my opinion he is the greatest of them all.”

QUIZ: How well do you know Charles Rennie Mackintosh?

Glasgow-based Mackintosh scholar and gallery-owner Roger Billcliffe believes Mackintosh continues to serve the city of his birth in a variety of ways, not least economically.

It is hoped that the Mackintosh 150 events and activities will draw hundreds of thousands visitors from Glasgow residents and tourists, as well as significantly increasing interest across Mackintosh sites, resulting in a multi-million pound tourism boost.

“Mackintosh matters very much,” explains Billcliffe, who has been involved in the study and conservation of Mackintosh works since the 1960s. “Like many post-industrial cities, Glasgow relies on service industries and at the heart of that is tourism. Mackintosh bring people to Glasgow. You simply can’t see his work in the same depth anywhere else.

“His appeal is wide. You can just be a casual tourist and enjoy seeing Mackintosh. He’s there when they open the guidebook and they plan him into their trip.

“People go to Edinburgh to see the castle and they come to Glasgow to see Mackintosh.

“One of the things I notice at the gallery is that people often come in with family and friends who are visiting from elsewhere, and you hear them talking about Mackintosh’s influence. Glaswegians are very aware of what he’s done and there is a real pride in this local boy made good.”

Although Mackintosh was celebrated in Europe and had a significant influence on the Vienna Secessionist movement, which included artists such as Gustave Klimt, he died in London in 1928, at the age of 60, without his output or genius receiving recognition at home.

What might have been, had Mackintosh lived longer, or if he had been acknowledged in his lifetime, is one of the questions that keeps Billcliffe engaged after 50 years of study.

“Fashion picks up and drops people all the time,” he says. "Mackintosh matters because the importance of what he did hasn’t changed. He’s still the leading architect of his generation in Britain, despite having produced relatively few buildings, and he remains a leading master of originality in furniture design. In places like Germany, Austria, the US and Japan he is viewed as someone who pointed the way.

“Sadly, he didn’t get the opportunity to fully develop. Mackintosh’s last building was 1910.

“It’s interesting, because Frank Lloyd Wright [the great American modernist architect] was born in the same year as Mackintosh, and he was still designing in the 1950s. What would Mackintosh have designed, I wonder, if he had been working in America with Frank Lloyd Wright’s wealthy clientele.”

But for Billcliffe, the most remarkable thing of all is the way Mackintosh’s work still has the power to surprise.

“I like the unpredictability and playfulness,” he says. “You come into a room and the light hits in a different way and you think, ‘wow, I’ve never seen that before’. He knew that was going to happen because he totally immersed himself in whatever he was doing. He can still surprise us.”

Mackintosh on film

Mackintosh's modern, geometric lines have proved appealing to film directors over the years, while the placing of his chairs is often used to signify a character's appreciation of modernity.

Blade Runner

The most famous appearance of Mackintosh’s furniture on film features the Argyle chair in Ridley Scott’s revered 1982 sci-fi thriller starring Harrison Ford. The chair appears in the apartment of protagonist Deckard, in an encounter with the android Rachel, played by Sean Young. The sits within a retro-futuristic set inspired by the interiors of Mackintosh's contemporary, Frank Lloyd Wright.

The Addams Family

The Argyle chair also appears up in the 1991 film The Addams Family, transposed to mock-gothic grandeur. Angelica Houston as Morticia, and Christiana Ricci as Wednesday Addams, are seen sitting on the chairs in a seance scene.

Inception

Christopher Nolan uses an elaborate Japanese-influenced interior scheme originally designed by Mackintosh for the Willow Tea Rooms in his multi-layered 2010 sci-fi film, Inception.

Mackintosh references run throughout a whole section section of the film, which stars Leonardo DiCaprio.

American Psycho

The cult classic, starring Christian Bale, features a high-backed Mackintosh in the New York apartment of the central character, wealthy sociopathic murderer Patrick Bateman.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here