Imagine that it is the summer of 1936 and you are on honeymoon in Germany. The sun is shining, the people are friendly – life is good. You have driven south through the Rhineland, admiring its castles and vineyards, and have watched fascinated as the huge, heavily laden barges ply their way slowly up the Rhine. Now you are in Frankfurt. You have just parked your car, its GB sticker prominently displayed, and are about to explore the city, one of the medieval architectural gems of Europe. Then, out of nowhere, a Jewish-looking woman appears and approaches you. Radiating anxiety she clutches the hand of a limping teenage girl wearing a thick built-up shoe. All the disturbing rumours you have heard about the Nazis – the persecution of Jews, euthanasia, torture and imprisonment without trial – are at that moment focused on the face of this desperate mother. She has seen your GB sticker and begs you to take her daughter to England.

What do you do? Do you turn your back on her in horror and walk away? Do you sympathise but tell her there is really nothing you can do? Or do you take the child away to safety? I first heard this true story from the daughter of the English couple, as we sat in her tranquil Cambridge garden sipping lemonade one hot summer afternoon. When Alice showed me the photograph of a smiling Greta holding her as a baby, confirming the remarkable and happy outcome of this particular traveller’s tale, I tried to place myself in her parents’ shoes. How would I have reacted had I found myself in the same situation? It took only seconds to conclude that, however touched by the woman’s plight and no matter how appalled by the Nazis, I would almost certainly have opted for the middle course. But although it is easy enough to imagine our response in such circumstances, do we really know how we would react? How we would interpret what is going on right in front of our eyes?

My new book describes what happened in Germany between the wars. Based on first-hand accounts written by foreigners, it creates a sense of what it was actually like, both physically and emotionally, to travel in Hitler’s Germany. Scores of previously unpublished diaries and letters have been tracked down to present a vivid new picture of Nazi Germany that it is hoped will enhance – even challenge – current perceptions. For anyone born after the Second World War, it has always been impossible to view this period with detachment. Images of Nazi atrocities are so powerful that they can never be suppressed or set aside. But what was it like to travel in the Third Reich without the benefit of post-war hindsight? How easy was it then to know what was really going on, to grasp the essence of National Socialism, to remain untouched by the propaganda or predict the Holocaust? And was the experience transformative or did it merely reinforce established prejudices?

These questions, and many others, are explored through the personal testimony of a whole range of visitors. Celebrities like Charles Lindbergh, David Lloyd George, the Maharajah of Patiala, Francis Bacon, the King of Bulgaria and Samuel Beckett, to name just a few. But also ordinary travellers, from pacifist Quakers to Jewish boy scouts; African-American academics to First World War veterans. Students, politicians, musicians, diplomats, schoolchildren, communists, poets, journalists, fascists, artists and, of course, tourists – many of whom returned year after year to holiday in Nazi Germany – all have their say, as well as Chinese scholars, Olympic athletes and a pro-Nazi Norwegian Nobel laureate. The impressions and reflections of these assorted travellers naturally differ widely and are often profoundly contradictory. But drawn together they generate an extraordinary three-dimensional picture of Germany under Hitler.

Many people visited the Third Reich for professional reasons, others simply to enjoy a good holiday. Yet more were motivated by a long love affair with German culture, family roots or often just sheer curiosity. Against a background of failing democracy elsewhere and widespread unemployment, right-wing sympathisers went in the hope that lessons learned from a ‘successful’ dictatorship might be replicated back home while those subscribing to a Carlylean worship of heroes were eager to see a real Übermensch [superman] in action.

But no matter how diverse the travellers’ politics or background, one theme unites nearly all – a delight in the natural beauty of Germany. You did not have to be pro-Nazi to marvel at the green countryside, the vineyard-flanked rivers or the orchards stretching as far as the eye could see. Meanwhile, pristine mediaeval towns, neat villages, clean hotels, the friendliness of the people and the wholesome cheap food, not to mention Wagner, window-boxes and foaming steins of beer, drew holiday-makers back year after year even as the more horrific aspects of the regime came under increasing scrutiny in their own countries. It is, of course, the human tragedy of these years that remains paramount, but the extraordinary pre-war charm of such cities as Hamburg, Dresden, Frankfurt or Munich, highlighted in so many diaries and letters, serves to emphasise just how much Germany – and indeed the whole world – lost materially because of Hitler.

Travellers from America and Britain vastly outnumbered those from any other country. Despite the Great War, a large section of the British public considered the Germans close kin – in every way more satisfactory than the French. Martha Dodd, daughter of the American ambassador to Germany, expressed a common view when she remarked, ‘Unlike the French, the Germans weren’t thieves, they weren’t selfish and they weren’t impatient or cold or hard.’ In Britain there was also growing unease over the Treaty of Versailles, which, as many now acknowledged, had given the Germans a particularly raw deal. Surely the time had come to offer this reformed former enemy support and friendship. Furthermore, many Britons believed that their own country had much to learn from the new Germany.

So, even as awareness of Nazi barbarity deepened and spread, Britons continued to travel to the Reich for both business and pleasure. According to the American journalist Westbrook Pegler, writing in 1936, the British ‘have an optimistic illusion that the Nazi is a human being under his scales. Their present tolerance is not acceptance of the brute so much as a hope that by encouragement and an appeal to his better nature, he may one day be housebroken.’ There was much truth in this. By 1937 the number of American visitors to the Reich approached half a million per annum. Intent on enjoying their European adventure to the full, the great majority viewed politics as an unwelcome distraction and so simply ignored them. This was easy to do since the Germans went to great lengths to woo their foreign visitors – especially the Americans and the British.

There was another reason why American tourists were reluctant to question the Nazis too closely, particularly on racial matters. Any derogatory comment regarding the persecution of Jews invited comparison with the United States’ treatment of its black population – an avenue that few ordinary Americans were anxious to explore. Most tourists, looking back on their pre-war German holidays, genuinely believed that they could not have known what the Nazis were really up to. And it is true that for the casual visitor to holiday hotspots like the Rhineland or Bavaria, there was limited overt evidence of Nazi crime.

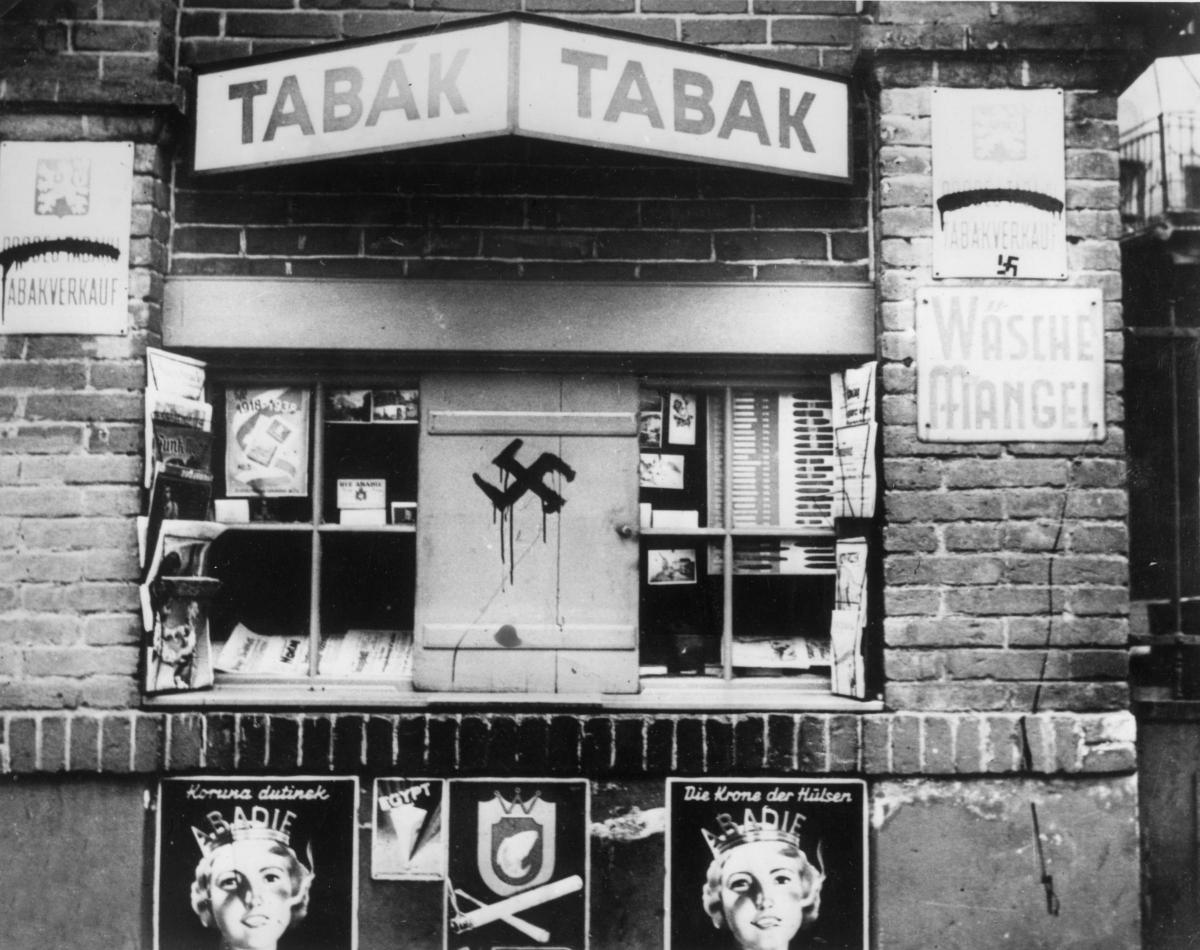

Of course, foreigners noticed the profusion of uniforms and flags, the constant marching and heiling but wasn’t that just the Germans being German? Travellers frequently remarked with distaste on the abundance of anti-Semitic notices. But, however unpleasant the treatment of Jews, many foreigners considered this to be an internal matter and not really their business. Moreover, as they were so often themselves anti-Semitic, many accepted that the Jews did indeed have a case to answer. As for newspaper attacks on the Reich, these were often discounted since everyone knew journalists’ penchant for sensationalising the least little incident. People also remembered how German atrocities reported in the newspapers during the early weeks of the First World War were later proven to have been false. As Louis MacNeice put it:

But that, we thought to ourselves, was not our business

All that the tripper wants is the status quo

Cut and dried for trippers.

And we thought the papers a lark

With their party politics and blank invective

While much of the above may have been true for the average tourist, what of those who travelled in the Third Reich for professional reasons, or who went specifically to explore and understand the new Germany? In the early months of Nazi rule, many foreigners found it difficult to know what to believe. Was Hitler a monster or a marvel? Although some visitors remained agnostic, the evidence suggests that, as the years went by, the majority had made up their minds even before they set foot in the country.

They went to Germany (as indeed they did to Soviet Russia) intent on confirming rather than confronting their expectations. Surprisingly few, it would seem, underwent a change of heart as a direct result of their travels. Those on the right therefore found a hard-working, confident people, shaking off the wrongs they had suffered under Versailles while at the same time protecting the rest of Europe from Bolshevism. To them, Hitler was not only an inspirational leader but also – as one enthusiast after another was so keen to state – a modest man, utterly sincere and devoted to peace.

Those on the left, meanwhile, reported a cruel, oppressive regime fuelled by obscene racist policies using torture and persecution to terrorise its citizens. But on one aspect, both could agree. Adored by millions, Hitler had the country totally in his grip.

Students form a particularly interesting group. It seems that even in the context of such an unpleasant regime, a dose of German culture was still considered an essential part of growing up. But it is hard to find an explanation for why so many British and American teenagers were sent off to Nazi Germany right up until the outbreak of war. Parents who despised the Nazis and derided their gross ‘culture’ showed no compunction in parcelling off their children to the Reich for a lengthy stay.

For the young people in question, it was to prove an extraordinary experience, if not exactly the one originally proposed. Students certainly numbered among those who, on returning from Germany, tried to alert their families and friends to the lurking danger. But public indifference or sympathy with Nazi ‘achievements’, cheerful memories of beer gardens and dirndls, and, above all, the deep-seated fear of another war, meant that too often such warnings fell on deaf ears.

Dread of war was the most important factor in many foreigners’ responses to the Reich but this was especially acute among ex-servicemen. Their longing to believe that Hitler really was a man of peace, that the Nazi revolution would in time calm down and become civilised and that Germany’s intentions were genuinely as benign as its citizens kept promising, resulted in many of them travelling frequently to the new Germany and offering it their support. The possibility that their sons would have to endure the same nightmare that they had, against the odds, survived makes such an attitude easy to understand. Perhaps, too, Nazi emphasis on order, marching and efficiency was innately appealing to military men.

The spectacular torchlight processions and pagan festivals that formed such a prominent feature of the Third Reich were naturally much remarked on by foreigners. Some were repelled but others thought them a splendid expression of Germany’s new-found confidence. To many it seemed that National Socialism had displaced Christianity as the national religion. Aryan supremacy underpinned by Blut und Boden [blood and soil] was now the people’s gospel, the Führer their saviour. Indeed numerous foreigners, even those who were not especially pro-Nazi, found themselves swept up in the intense emotion generated by such extravaganzas as a Nuremberg rally or massive torchlight parade.

No one knew better than the Nazis how to manipulate the emotions of vast crowds, and many foreigners – often to their surprise – discovered that they too were not immune. All travellers to the Reich, no matter who they were or what their purpose, were subjected to constant propaganda: the iniquities of the Versailles treaty, the astonishing achievements of the Nazi revolution, Hitler’s devotion to peace, the need for Germany to defend itself, retrieve its colonies, expand to the East and so on. But arguably the Nazis’ most persistent propaganda message, and the one that they initially felt certain would persuade the Americans and British to join forces with them, concerned the ‘Bolshevik/Jewish’ threat.

Foreigners were lectured incessantly on how only Germany stood between Europe and the Red hordes poised to sweep across the continent and destroy civilisation. Many became inured and stopped listening. Indeed, trying to figure out the precise difference between National Socialism and Bolshevism was for the more questioning traveller a confusing matter. They knew, of course, that the Nazis and communists were the bitterest of enemies, but what exactly was the difference between their respective aims and methods? To the untrained eye, Hitler’s suppression of all personal freedom, control of every aspect of national and domestic life, use of torture and show trials, deployment of an all powerful secret police and outrageous propaganda, looked, superficially at least, remarkably similar to Stalin’s.

As Nancy Mitford frivolously wrote: ‘There’s never been a pin to put between Communists and the Nazis. The Communists torture you to death if you are not a worker and Nazis torture you to death if you are not a German. Aristocrats are inclined to prefer Nazis while Jews prefer Bolshies.’

Until 1937, when the anti-Nazi chorus grew much louder, it was the journalists and diplomats who, with some obvious exceptions, emerge as heroes. Travelling widely all over the country in their efforts to present an accurate picture, these men and women consistently tried to draw attention to Nazi atrocities. But their reports were repeatedly edited or cut, or they were accused of exaggeration. Many worked long years in Germany under nerve-racking conditions and, in the case of the journalists, with the knowledge that at any minute they might be expelled or arrested on trumped-up charges. Their travel accounts are very different from the joyous descriptions so often found in the diaries and letters of the short-term visitors who much preferred to believe that things were not nearly as bad as the newsmen made out.

While it is natural that informed residents should perceive a country differently from the casual tourist, in the case of Nazi Germany, the contrast between the two viewpoints is especially striking. From a post-war perspective, the issues confronting the 1930s traveller to Germany are too easily seen in black and white. Hitler and the Nazis were evil and those who failed to understand that were either stupid or themselves fascist. My book does not pretend to be a comprehensive study of foreign travel in Nazi Germany, but it does, through the experiences of dozens of travellers recorded at the time, attempt to show that gaining a proper understanding of the country was not as straightforward as many of us have assumed. Disturbing, absurd, moving and ranging from the deeply trivial to the deeply tragic, these travellers’ tales give a fresh insight into the complexities of the Third Reich, its paradoxes and its ultimate destruction.

Travellers in the Third Reich: The Rise of Fascism Through the Eyes of Everyday People by Julia Boyd is published on 10 May by Elliott & Thompson, £10.99 paperback.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here