IN 1962 the British Iron and Steel Federation had good reason to feel confident about the future of the industry. For a start, it was made up of no fewer than 300 companies, all of them manufacturing pig iron or making, shaping and treating steel.

Writing in a careers supplement in the Herald that April, J.Kelly, Scottish area training officer at the federation, said the industry had spent vast sums on development since the war and was now engaged on a programme “of unprecedented technical innovation and expansion.”

Spending on capital equipment was currently running at £4 million a week; “a considerable part of this expansion has been in Scotland, perhaps the most widely-known aspect being the strip mills of Colvilles Ltd, at Ravenscraig and Gartcosh in Lanarkshire”.

The industry was proud of its reputation for quality products, its good industrial relations, and its “important contribution” to Britain’s economic prowess.

There were many career opportunities for young people with varying abilities, aptitudes and qualifications. “Today, more than ever”, Kelly went on, “the iron and steel industry is looking to the future. Young people entering the industry now will find training schemes and expert guidance to help them to build a worthwhile and satisfying career”.

Read more: Herald Diary

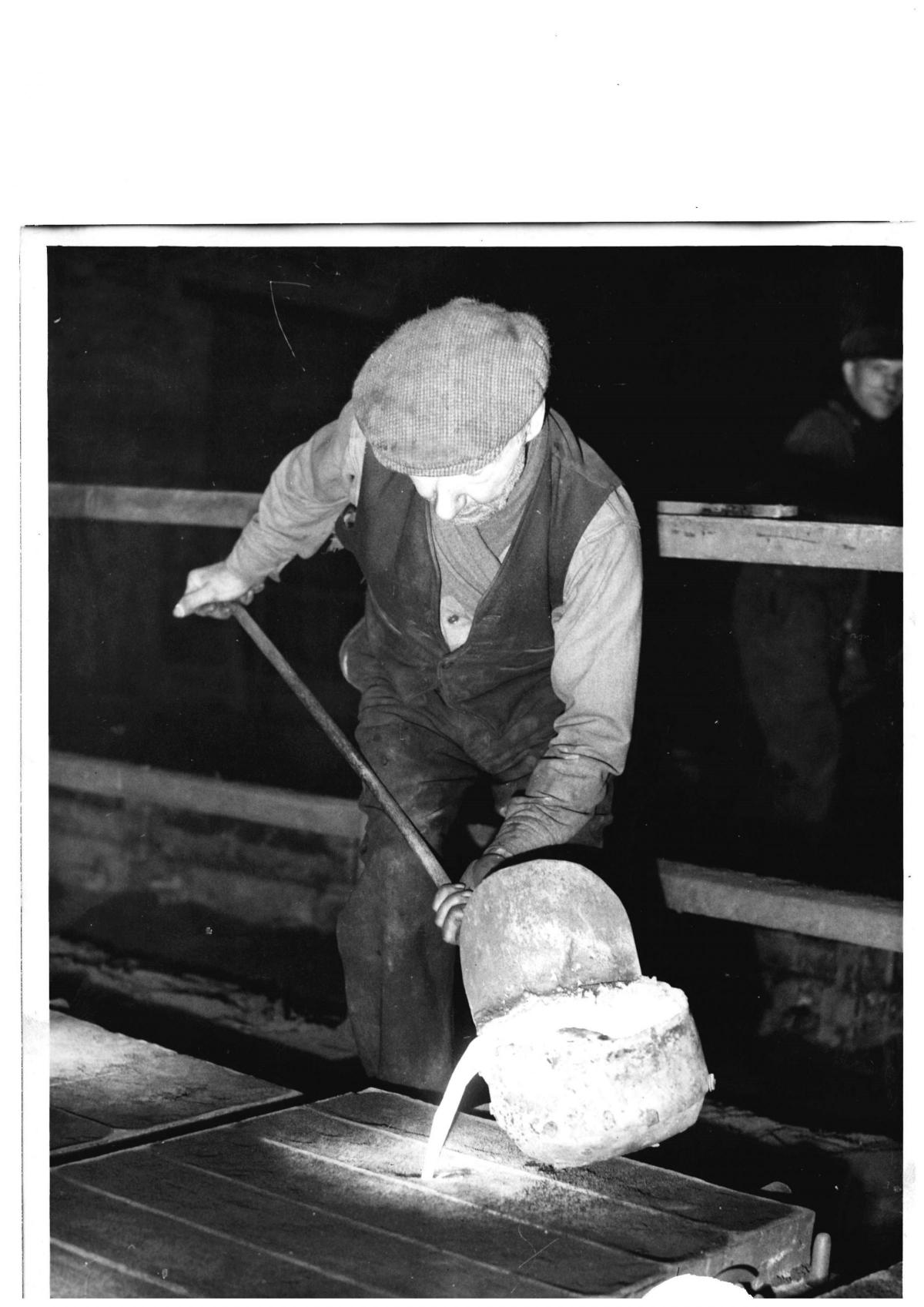

If one man knew that such a career could be worthwhile and satisfying, it would have been Charlie Miller (above).

In 1951, nine years before the federation’s article in the Herald, a reporter and photographer from The Bulletin had watched as this “small, rosy-faced man” picked up a half-hundredweight ladle full of molten metal “and nimbly trotted away to tip it in a mould”.

Charlie, 81, was celebrating his 70th year as a moulder, and for the past 40 years he had worked at the Allan Ure iron foundry at Keppochhill, Glasgow. He had been born in Falkirk, his parents having resettled there from Forres, Morayshire. “Nothing would do me but get a black face”, he said, explaining why he had got a job in a Falkirk foundry at the age of 11. As a lad he had regularly worked from 6am to 5.30am. “It never did me any harm. A lot of people nowadays wouldn’t work at all if they could”.

He remained a keen fan of Falkirk FC, travelling to their Brockville ground from Glasgow to see them play.

Charlie grew mildly indignant when asked if he intended to continue working. “Why should I ‘no’?” he asked, adding that he had never had any worries or illness. When he turned 80 in 1950, his workmates had a celebration for him but, said The Bulletin, “he was not ‘pampered’ in any way, and can hold his own with workers 60 years his junior”.

“Wish there more like Charlie”, mused James Colman, 60, the foundry manager. “He’s a first-class, steady worker, and only sickness will keep him away from his job”.

The photograph on the right shows men at work in the moulding shop at Kirkintilloch’s Lion Foundry in 1969.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here