“IS the traditional market the unacceptable face of Glasgow as it turns its sand-blasted profile to the future or does it represent not just happy memories but survival for many of the city’s poorest people?”

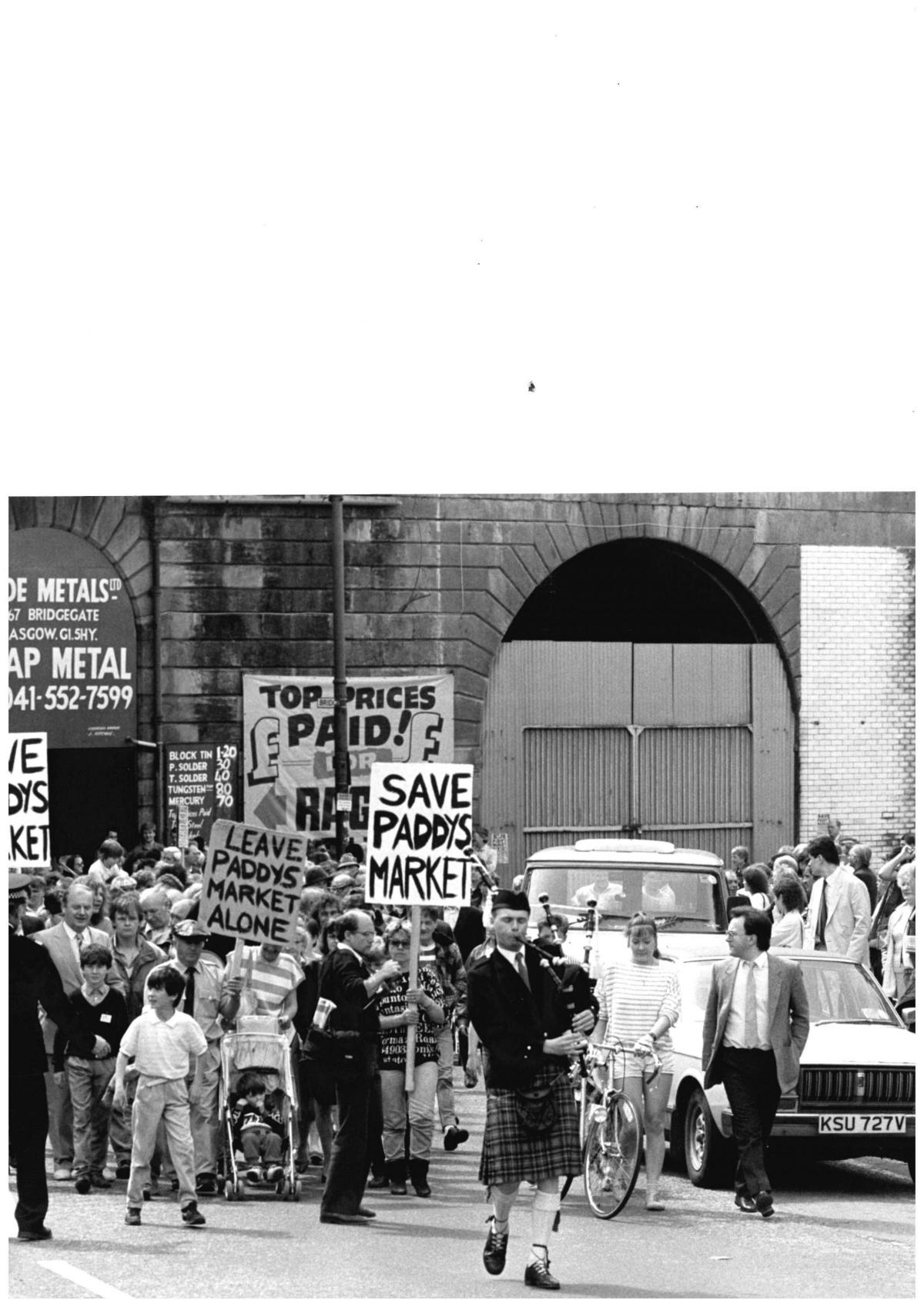

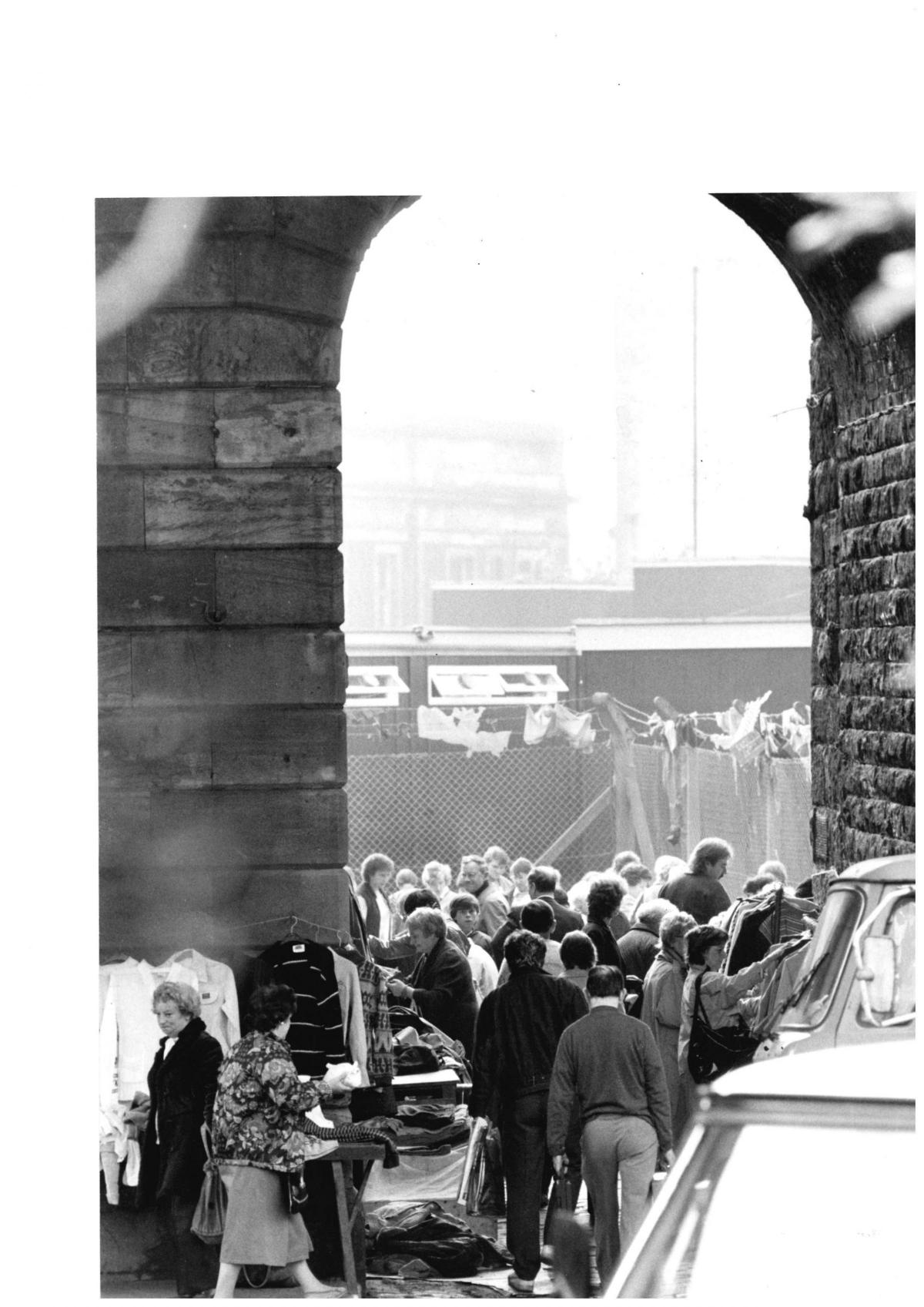

It was an interesting question, posed by this newspaper in July 1987 as 200 Paddy’s Market stall-holders and hawkers, “under threat from planners who feel that its image does not fit in with the shining new face of the Miles Better City”, staged a protest march (right, photographed by Ian Hossack, who also shot the main image, in 1985).

The protesters, led by a piper and Glasgow Provan MP James Wray, himself a regular market shopper, brought traffic to a standstill as, armed with a 25,000-signature petition, they walked to the City Chambers. The district council and other agencies were at the time studying a report that recommended that the market area of the Bridgegate and Shipbank Lane be redeveloped for private housing and crafts shops.

“We will not allow the planners to ride rough-shod over the people who need this market”, said Mr Wray. “Poor people spend five pounds there as happily as the rich spend five thousand pounds at Harrods. We have to stop the speculators getting their hands on a market which has been in this area for a hundred and fifty years. It provides a social service for the poor in a city with massive unemployment”.

Herald writer Maurice Smith said that Paddy’s was seen by “the self-styled pioneers of a New Glasgow ... as the unacceptable face of the city.” (The European City of Culture reign was just three years away). “Yet to thousands of Glaswegians it represents happy memories: The cherished bargains from among the second-hand furs adorning racks in the Shipbank Lane archways; the colourful patter of the hawkers as they ply their trade along the cobbled lane outside”.

“This is a living landmark”, said stallholder Michael Taplin, head of the market people’s action committee. We are fighting for our livelihoods. Glasgow has a history of bulldozing places, but usually it can correct any mistakes. If they get rid of Paddy’s, it can’t be brought back - the mistake will be there forever ... If people want to smell the smell and see the dirt, then they will. But there are some pearls in all the dirt. We don’t force it on anybody else”. On this occasion, Paddy’s was saved after the market traders reached agreement with British Rail, owners of Shipbank Lane, to improve the area.

Read more: Herald Diary

Throughout its long life, the market faced several threats to its existence. In 1911, local shop-owners urged its closure because it threatened their trade. The Weekly Herald sent a reporter to that “alfresco bazaar in Great Clyde Street” to see what the fuss was about.

The end came for Paddy’s Market ten years ago. Reports said the council had declared the market to be a “crime-ridden midden” and announced a “new vision”, including plans to revitalise the area and lease units to artists and “legitimate traders”.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here