IN his excellent book, Britain’s War: Into Battle 1937-1941, the historian Daniel Todman describes the outbreak of war as “the greatest anti-climax in modern history”.

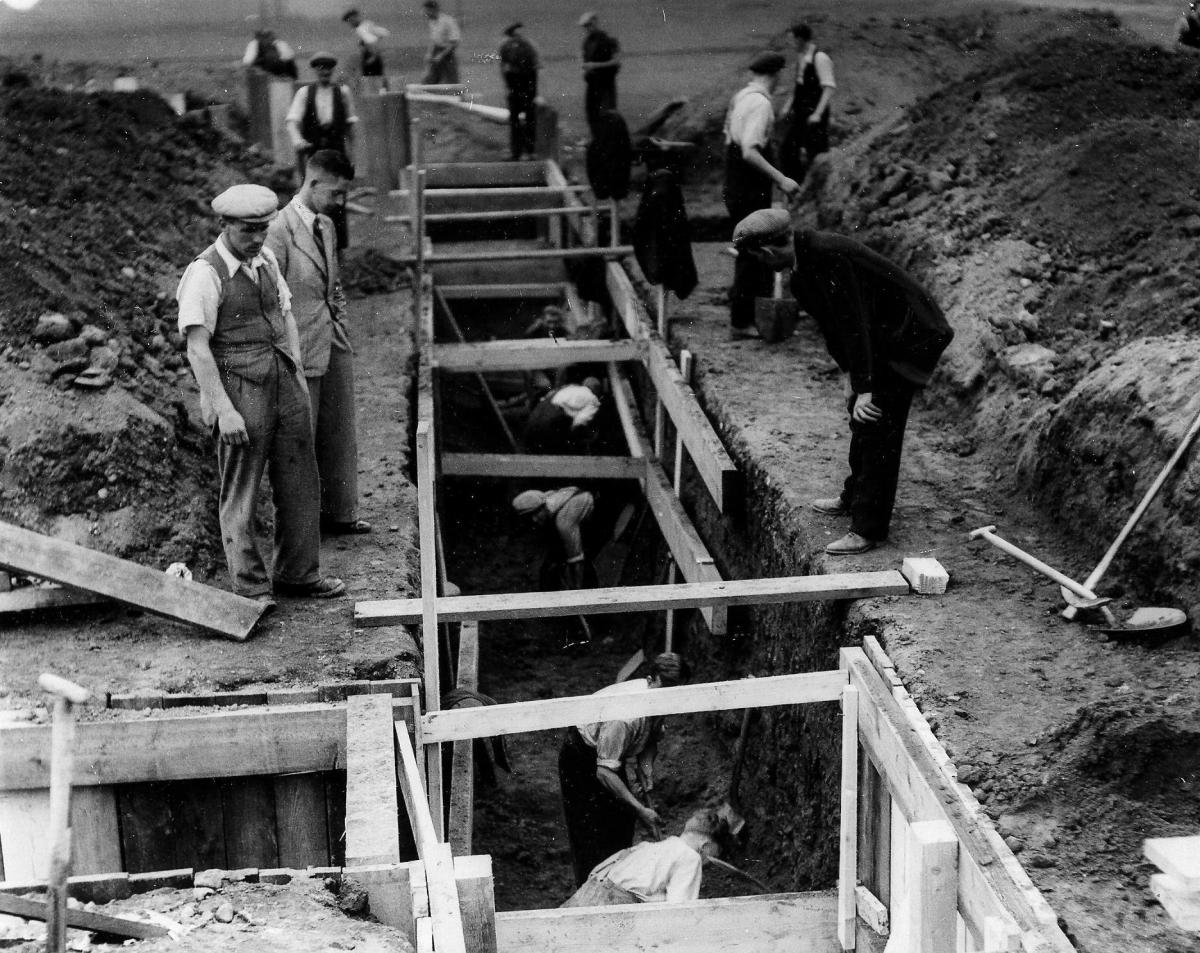

As news of the declaration of war on September 3, 1939, was being relayed by, for example, young street-vendors selling the Evening Times, recruiting for local defence services was continuing at a brisk rate. Sandbag walls were being erected outside hospitals and shops, and trenches were being dug in public parks (right) to serve as air-raid shelters.

Though the liner, SS Athenia, was sunk on September 3, the opening weeks of the war were quiet. As Todman records, it took until October 16 for the first British civilian to be hurt in an air-raid - a housepainter in Leith, as it turned out. Despite frequent false alarms in those weeks, “the aerial apocalypse was markedly absent”.

By October 6, the Poles had been defeated. On the Western Front, French and British troops remained on the offensive. "This was not what the all-devouring contest for the future of civilisation was meant to be like”, Todman continues. “Before long, Britons were calling it the ‘Bore War’. Later, they would come to use the Americanism, ‘Phoney War’.”

Writing in the Evening Times in 1980, the author and broadcaster Bo Crampsey gave a vivid picture of that period.

He and his brothers were the only children in Mount Florida not to have been evacuated at the outbreak of war. Six weeks later, the Luftwaffe having failed to appear, their friends returned from their countryside billets.

“The greatest change in our habits was caused by the black-out and each of us was issued with a torch”, Crampsey wrote. “Brown paper was stuck on the glass, leaving only a pin-point of light. We shone this dim ray hopefully in the direction of the sky, but without result, even when we made up semaphore messages for the hovering Germans.

"We had to carry our gas-masks everywhere: no admission to cinema or football match without them was the order of the day”.

Occasionally, the war was enlivened by episodes such as the Battle of the River Plate, which would encourage kids to revive their war-games. “Curiously, all the competition was to be a German naval officer, so that one could extend the right arm stiffly and utter such compelling phrases as ‘Very good, Herr Kapitan Deutschland!’”

Even at the age of 10, Bob had a sceptical view of the cinema newsreel commentaries: “The commentators had three tones of voice. Mark 1- Britain can take it, not that we’d taken much at that time. Mark 2 - Britain can dish it out, not that we’d ...etc. Mark 3- Heavily facetious. Humour was denoted by referring to Hitler as Schickelgruber, his real name. In fairness, the Hitler of 1940 could not be seen as the maniac of 1945”.

*Tomorrow: More of Bob’s recollections of 1939-1940

Read more: Herald Diary

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel